| Egads, foiled again.

That irreverent thought kept flashing through my

brain as I ground, sanded, puttied, and faired my

way through a revision of Oaracle’s leeboard

and rudder. In my mind, of course, were two recent

articles in Duckworks that had addressed getting airfoil

shapes on leeboards, centerboards and rudders. Based

on those examples, my goal was to achieve a foil shape

to improve performance – and maybe durability

– without too much pain and aggravation, but

taking a different route than those suggested by the

other two worthy articles.

Some background. Oaracle is a Jim

Michalak-designed

Frolic2. Like all the small boats

I have built, its foils are a bit rounded at the leading

edge, a bit tapered at the trailing edge, and slab

sided in between. Sure airfoil shapes are supposed

to be more efficient, but exactly how much and whether

it would justify a lot of potentially nit-picky (i.e.,

stuff I’m not that good at) work was uncertain.

|  Here’s

Oaracle back before I made the modifications

to the rudder and leeboard. Here’s

Oaracle back before I made the modifications

to the rudder and leeboard.

|

Four factors combined to lever me out of slab-sided

complacency.

The first was Tom Hamernik’s excellent foil

programs available free through Duckworks.

Tom has released two versions and either works. All

you have to do is specify what NACA section foil shape

you want and the width and thickness of your board

and, voila, you get a graphed cross section. Neat.

Second was Warren Messer’s recent article

on how he made NACA 10 section foils for one of his

boats using 1/8-inch plywood and thickened epoxy.

For the first time, doing a proper foil shape seemed

doable. But I saw two problems. One is 1/8 waterproof

ply is nonexistent where I live and shipping in a

piece or two doubles the price. The other is I already

had a leeboard and rudder and it seemed wasteful to

start from scratch on new ones instead of shaving

down the existing ones. (When Pat Patteson’s

excellent

article appeared about making hollow

foil-shaped boards, I was already well along on my

modifications. Besides, there still was the problem

of wanting to use the existing boards. . . .)

The third impetus was some conversations with noted

small boat designer and sailor Matt Layden at this

year’s Everglades Challenge and Cedar Key events.

I had observed that the leeboard and rudder on Matt’s

Sand Flea, an innovative 8-foot punt, had foil shapes.

In response to my queries, Matt said doing a foil

would not produce a huge improvement, but in his opinion

was worth the effort. He also agreed that it was practical

to shave down the existing leeboard and rudder, rather

than start from scratch with new ones. Since there

are several varieties of NACA foils, I asked for his

recommendation. Matt said a NACA 9 section for the

leeboard and a NACA 6 section for the rudder would

be his choice. His final advice was not to obsess

about getting micromillimeter precision, but just

to get close. (Such accuracy is beyond my abilities

anyway.)

The fourth reason has nothing to do with a foil

shape but rather protecting the leading edges of the

fins. Tom Lathrop, who helped Graham Byrnes build

his winning design for the 2007 Everglades Challenge,

wrote (on the forum

section of www.messing-about.com/index.php)

about epoxying a resin-saturated Dacron rope on the

leading edge of the centerboard. He said he had been

doing it for 20 years to the leading edges of centerboard,

rudders, and the like and never had to replace one.

(You can find his account here)

It sounded worth trying. (John Guzzwell, in his book

on cold-molded boat building, recommended sheathing

the hulls with Dynel cloth, which is polyester, not

fiberglass. He reported the Dynel, while adding little

strength, could take an amazing amount of abrasion.)

The project was begun with some trepidation but

it was much easier from start to finish than I anticipated.

To be fair, I neither tried nor achieved micromillimeter

precision. But by my standards, it did come out much

better than expected.

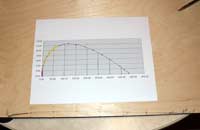

The first part was to call up Tom Hamernik’s

programs. This was sheer simplicity. Simply pick the

NACA section you want, then plug in the thickness

and width of the leeboard or rudder. You instantly

get a graph of the half cross section of the foil,

that exaggerates the thickness to better show the

curve. The graph used to make a full size template,

using either thick cardboard, balsa wood, or thin

model-making basswood ply.

|  Tom

Hamernik’s foil program prints out a graphed

cross section of the chosen foil shape, with

the thickness exaggerated. Here’s the

graph and the ply template that was made from

it. One was done for the leeboard and another

for the rudder. Tom

Hamernik’s foil program prints out a graphed

cross section of the chosen foil shape, with

the thickness exaggerated. Here’s the

graph and the ply template that was made from

it. One was done for the leeboard and another

for the rudder.

|

|  Here’s

the template on a flat surface... Here’s

the template on a flat surface...

|

|  ...

and on the original, slab sided leeboard. If

you look closely at this shot, you can see it’s

quite a ways off the foil shape. ...

and on the original, slab sided leeboard. If

you look closely at this shot, you can see it’s

quite a ways off the foil shape.

|

Next is the nerve-wracking part. Using the tool

of your choice – hand plane, power plane, grinder,

drawknife, etc. – carve down the foil to match

the template. Even though the leeboard and rudder

were covered with a layer of fiberglass, I planned

to used my old power planer, having learned it can

go through a layer of glass with little problem. But

the planer chose this moment to wear out, or at least

indicate it needs a new pair of brushes, which weren’t

on hand. So it was down to the local discount tool

emporium. I picked up a small angle grinder with a

sanding disc attachment for much less than the cost

of a replacement planer. The 24-grit sandpaper proved

more than a match for the glass and laminated ply

of the foils.

|  After

only a few minutes with the angle grinder, quite

a lot of wood has been removed. After

only a few minutes with the angle grinder, quite

a lot of wood has been removed.

|

|  The

board is nearly ready for glassing on both sides. The

board is nearly ready for glassing on both sides.

|

The hardest part of shaping the foils was to remember

to stop every couple minutes to check with the template

to make sure I didn’t go too far, too fast –

that grinder really removed the wood!

|  Use

the template to check the developing shape frequently.

Also take come care to ensure you’re not

skewing the shape by leaving it too thick or

thin at the front or back edge. That shouldn’t

be too hard if you’re working with a new,

unpainted boat as you can see the centerline

of the glued up ply layers (at least if you

have an even number of layers). This board had

been painted, so some care was needed to make

sure the two sides came out symmetrical. In

this shot, the shape is getting pretty close. Use

the template to check the developing shape frequently.

Also take come care to ensure you’re not

skewing the shape by leaving it too thick or

thin at the front or back edge. That shouldn’t

be too hard if you’re working with a new,

unpainted boat as you can see the centerline

of the glued up ply layers (at least if you

have an even number of layers). This board had

been painted, so some care was needed to make

sure the two sides came out symmetrical. In

this shot, the shape is getting pretty close.

|

(If you do take off too much, you can fair over

the error with thickened epoxy.) It took about 90

minutes using the grinder and finishing with a belt

sander with 60-grit paper to shape the leeboard and

about half that time on the rudder. And that was making

a point to frequently check the shape with the templates.

Because a significant amount of wood was removed

from the leeboard, I decided to reglass it with two

layers instead of one. No scientific measurements

were taken, but it was interesting to see how, as

each layer was laminated to each side, there was appreciable

improvement in the board’s stiffness (and, hopefully,

strength).

Also I decided to vary the finishing details of

the leeboard and rudder out of curiosity. On the leeboard,

I did all the glassing, and then cut back the leading

edge and attached the Dacron rope. On the rudder,

I attached the rope first and then glassed the foil,

trimming the fiberglass even with the rope/board joint.

|  On

the rudder, I used a hand plane and belt sander

to put a flat face on the leading edge, ready

to take the epoxy saturated rope. On

the rudder, I used a hand plane and belt sander

to put a flat face on the leading edge, ready

to take the epoxy saturated rope.

|

|  The

leeboard was glassed before the leading edge

rope was attached. The lines from the layers

in the ply show up better here, and help guide

the shaping. These lines should have been a

little straighter, and I did some filling with

thickened epoxy after the board was glassed. The

leeboard was glassed before the leading edge

rope was attached. The lines from the layers

in the ply show up better here, and help guide

the shaping. These lines should have been a

little straighter, and I did some filling with

thickened epoxy after the board was glassed.

|

As long as you’re available to trim the glass

with a sharp knife in its “green” stage

(not sticky, but not at its final hardness) I don’t

think it matters which way it’s done. If you’re

not going to be around to trim the glass when its

green, I’d do the glassing and then the rope.

On the leeboard, I used a circular saw to cut a flat

face on the leading edge of the board, and a power

sander to even up the cut and extend the flat face

around the curved edge on the bottom of the board.

On the rudder, I used a hand plane and finished with

the belt sander, and liked that method better.

In his writeup, Tom Lathrop said he used 3/8-inch

rope. He didn’t mention the thickness of the

board, but it looked about an inch and a half. Oaracle’s

leeboard is one-inch thick and I spent an unnecessary

amount of time obsessing which size rope I should

use, finally settling on 1/4-inch. Unfortunately,

I cut a bit more off the leeboard’s front edge

than anticipated, and the 1/4-inch seemed a bit too

small, so I grabbed a scrap of 3/8-inch and that seemed

like a good fit. It then dawned on me that the size

wasn’t that critical. Anything from 1/4-inch

to1/2-inch probably would have worked well, just so

it matches the size of the flat face cut into the

leading edge.

Tom recommended using soft, braided Dacron (he said

nylon would also work but he prefers the polyester),

and I’m assuming he meant the single braided

kind that has about 12-strands. I missed that detail

until after I had attached the ropes. The leeboard

got 3/8 inch double braided rope, the cheap stuff

now commonly available at hardware stores or the big

box home improvement outlets. Make sure you check,

some of these ropes are polypropylene which might

not saturate as well. The rudder got a scrap of 1/4-inch

yacht-grade double braided rope that was lying around.

The double braids are harder ropes, and probably didn’t

mold as well to the leeboards (see below) as the softer

rope would.

I used a somewhat simpler method of attaching the

rope; you can go to Tom’s write-up to see how

he did it. First before any epoxying is done, the

ropes were cut to length. Then a flat headed nail

(not a finish nail) was pushed through the center

at the top of the rope.

|  Use

a nail with a flat head to hold the rope in

place for a dry fit. Use

a nail with a flat head to hold the rope in

place for a dry fit.

|

Hammer the nail into the board at the top of the

flat area on the leading edge just enough to hold

it in place, being careful to get it centered. Stretch

the rope down the face and put in another nail at

the bottom, again centering the nail and the rope

on the flat edge. The tension will hold the rope in

place; it’s not necessary to put a groove in

the flat face. It’s also not necessary to stretch

it bar tight, just do it enough to hold the rope straight

and in place.

Now remove the rope from the board, leaving the

nails in the rope. The holes in the board will mark

where they need to be replaced. Cut some plastic sheeting

that is longer than the rope, and wide enough to drape

over the leading edge of the board and several inches

down each side. Use duct tape to fasten one edge to

the board, and then fold it back, exposing the flat

leading edge.

|  Here

the rope has been dry fitted with a nail at

each end holding it in position, and the plastic

has been taped on one side, ready to drape over

the soon-to-be-epoxy-saturated rope. Here

the rope has been dry fitted with a nail at

each end holding it in position, and the plastic

has been taped on one side, ready to drape over

the soon-to-be-epoxy-saturated rope.

|

Now mix up some epoxy and dunk the rope in it. I

used about 8 ounces for the 4-foot long 3/8 inch piece

for the leeboard, and probably could have got by with

4 to 6 ounces. Poke the rope with a stick for a couple

minutes to make sure air bubbles are disbursed and

the rope is thoroughly saturated. Take the rope out

(wearing gloves!) and place it, like you did before,

on the leading edge. Make sure you don’t hammer

the nails all the way down – you’ll want

to remove those when the glue dries (well, I suppose

you could use a Monel and bronze ring nails, but I

prefer to take them out). Now drape the plastic over

the saturated rope, pull it down firmly, and tape

it in place. It helps to have precut the pieces of

tape; trying to tear strips of duct tape with glue-covered

gloves is a frustration best left to others. You’ll

need pretty long pieces to fit over the bottom of

the board where the rope goes around the curved leading

edge.

|  The

rope has been removed, saturated with epoxy,

and replaced. The plastic is draped over the

rope, pulled tightly down, and taped firmly

in place. Note the long pieces of tape at the

bottom end to anchor that section. What to do

with the ends of the rope is up to the builder.

Tom Lathorp notched the bottom to fit the rope

and at the top anchored it in a hole. I wanted

until the epoxy had partially cured and then

flattened the ends, later going back and sanding

the hardened rope and using some thickened epoxy

to fair the ends. The

rope has been removed, saturated with epoxy,

and replaced. The plastic is draped over the

rope, pulled tightly down, and taped firmly

in place. Note the long pieces of tape at the

bottom end to anchor that section. What to do

with the ends of the rope is up to the builder.

Tom Lathorp notched the bottom to fit the rope

and at the top anchored it in a hole. I wanted

until the epoxy had partially cured and then

flattened the ends, later going back and sanding

the hardened rope and using some thickened epoxy

to fair the ends.

|

While the glue is still wet, run your hand over

the plastic covered rope. You can easily feel if it

has slipped off center anywhere and you can simply

move it back. There will (or should be) enough pressure

from the plastic to hold it in place. Now walk away

and let the epoxy cure.

An unrelated tip: If you regard epoxy as liquid

gold, try to have some other use lined up for the

left over epoxy used to saturate the rope. I didn’t

plan ahead when I did the leeboard. When I got to

the rudder a few days later, I made sure the excess

was used to fill the weave of the fiberglass cloth

on the leeboard.

Also, to state the obvious, you can use Dacron rope

to protect the leading edges of your boards and rudders

even if you don’t go to the trouble of shaping

them like foils.

|  The

joint between the rope and board has to be filled

with thickened epoxy The

joint between the rope and board has to be filled

with thickened epoxy

|

|  Here’s

the protective rope as it curves around the

bottom edge of the leeboard . . . Here’s

the protective rope as it curves around the

bottom edge of the leeboard . . .

|

|  ...

and the bottom edge of the rudder. Notice the

nice curve on the leading edge provided by the

ropes. I whacked the hardened rope with some

miscellaneous heavy objects and didn’t

managed to dent or mark it. Hopefully it will

stand up to rocks and oyster shells for many

years. ...

and the bottom edge of the rudder. Notice the

nice curve on the leading edge provided by the

ropes. I whacked the hardened rope with some

miscellaneous heavy objects and didn’t

managed to dent or mark it. Hopefully it will

stand up to rocks and oyster shells for many

years.

|

Anyway, once the epoxy is dry, you’re about

done. You’ll have a groove between the rope

and board (bigger if you use hard rope like I did,

smaller if you use softer rope like Tom recommends)

to fill with thickened epoxy – no big deal.

After that fill the weave of the glass cloth and fair

the boards to whatever standards you want or have

the patience for. I was pleasantly surprised when

I put the templates back on the leeboard and rudder

to find out the rope on the leading edges matched

exactly the curves on the templates. Sometimes you

gotta be lucky.

|  Glassing

the rudder, and filling the fiberglass weave

on the leeboard. All that’s left is sanding,

fairing, and painting. Glassing

the rudder, and filling the fiberglass weave

on the leeboard. All that’s left is sanding,

fairing, and painting.

|

Because of a minor shoulder ailment, it will be

a couple months before Oaracle is back in the water

and we get to try the revamped foils. But when I stood

back to look at the finished product, I couldn’t

help thinking, “Egads, I’ve been foiled.

And I’ll probably do it again. (When I build

another boat . . .)”

Other articles by Gary Blankenship &

Helen Snell:

|