| Part 1

Part2

I've been building so many boats lately, that I have

to stop and think about which one I am writing about

now. A peek in the shop shows that its the 10ft Nuthatch

that I've finally gotten around to constructing after

the PDF

model has been posted here at Duckworks

Magazine for over a year now. I think in the last

story

on building the PUD-g, I said I was next going to

start work on a driftboat design I had. That hull

has been put on hold for awhile so I can rethink the

size of the boat and make a few tweaks to the design.

But this story is about my first boats (the 8ft

Nuthatch) bigger brother the 10ft Nuthatch.

I also had several inquiries from readers as to when

I was ever going to get around to building it. So

here it is, and I'm going to spend more time with

this series of stories on the details that can cause

builders to throw down their tools and walk away from

their boat building projects. This part will deal

with the "big scary"in boat construction;

scarfing plywood to make longer sheets.

I have to admit that the thought of having to scarf

plywood breaks out the Costco sized bottle of Tums

for a quick hit. But once I have set up everything,

and start grinding away on the bevels, things improve.

It's just a mater of overcoming the initial fears

of a project. Like my first ever mix of epoxy, making

the first fillet, or ever working with fiberglass.

Baby steps turn into strides.

When I resized the lines from the 8ft to the 10

& 12ft versions of the Nuthatch, I made a decision

to change one of the side panel edges from a straight

line to an arc. This made a very big change in the

looks of the hull even though it added some extra

work in the lofting. But the extra effort in lofting

makes for a hull with more appealing lines. I love

holding the 10ft PDF model up on my finger tips and

just looking at it. Enough day dreaming and on to

building it.

I was conflicted on whether or not to use 5x10ft

sheets of plywood again on this hull or bite the bullet

and scarf. EdenSaw Woods made the decision for me

by being sold out of the 5x10 sheets of Okume or anything

else that might work. So it was time to practice my

scarfing abilities again. Scarfing is one of those

things that you have to work with a few times to become

really good at. Not to say that a first timer can't

do a good job; it can be done, but you have to be

diligent in your approach. Dave Nichols wrote a great

article

on scarfing earlier this year for Duckworks Magazine.

A good read and a lot of good information. I wanted

to take one last stab at scarfing a full stack at

one time, so I ordered my Anant

A8 plane online. I wanted to have a tool

long enough to cover the full face of the stacked

scarf and the upper and lower guide supports, and

maintain a "flat" surface. I had been using

a router mounted on a beefed up piece of plywood that

I ran up and down the scarf face. It worked ok, but

covered my shop in a layer of routed plywood chips;

and I mean covered. So I wanted to go in a quieter

and less dusty direction, and so the big hand plane.

I will keep using the plane, but will change my approach

to scarfing as you will read later.

|

|

One of the things I didn't do at the very start,

was to reread my own directions on setting up the

plywood sheets for scarfing. By that I mean, which

side goes up. In my rush to use the new plane, and

to cut the "partial extension sheets", I

forgot which sides go up, and which sides go down

in the stack. On a scarfed panel, the outside "tip"

of the scarf points aft. Part of the planing is to

determine the "good" side from the bad,

and which you want to go on the outside. If you are

going to have a wood finished interior, you want the

good surface [with 1088 marine plywood this is can

be a coin toss (mainly which grain pattern you like

best)] on the inside. I am a confirmed painter, so

I try to put the good side out; to give me the best

surface for using high quality marine enamels and

LPU

paints. The hull's insides have a lot

of glass taped edges, backing blocks, and hardware

fittings that take away from any overall appearances.

So I always go with good on the outside.

A keen Duckworks eye will see that I had all the

sheets, good side up in the stack. The correct way

would have the "longer" plywood sheets,

bad side up, and the "shorter" sheets, good

side up. Then when you epoxy the two pieces together,

the short sheet flips over and both bad sides are

up and the good side tip will point aft. The boat

will still float no mater how you do it, so don't

sweat the details. Worry about it on the next boat

you build, and enjoy the one(s) you have.

|

|

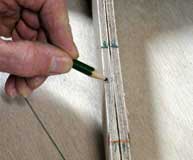

After the plywood sheets were squared up on the

sides and set back 3" each, it was time to break

out the new A8 hand plane. I did place some screws

in a few places to hold down any edges that wanted

to rise up. The screws were placed 3 1"2"

back from the leading edge to protect the plane's

blade. Having a level and flat surface to start with

is necessary for good results. Any vertical curves

in the plywood stack will become apparent when you

attempt to epoxy the mating faces together, and see

the horizontal arcs on the scarf edges. I also lifted

the whole stack 1/2", by placing spacers under

everything. I wanted to have a level and straight

support for the plywood sheet at the bottom of the

stack. The "extended and squared" support

also gave me something for the hand plane to use as

a lower guide, and some waste material to be planed

down as the scarf bevel deepened. This support piece

also helps keep the "thinning" edge from

being blown out.

|

|

So I set the depth of the plane's "iron"

(lets be proper with names) and started with the first

long stroke. Have you thought about how much wood

I will be removing???? I hadn't ever thought about

it before, but was soon to learn. I have to cut bevels

3" wide, by 1/4" deep on one side, with

a running length of 16ft. That's taking a piece of

wood 1/2" thick, by 3" wide, by 4ft long

and planning it to oblivion. No wonder I was sweating

after a few minutes, and I had to spread the sweat

out over a couple of days. My arms thought they were

in boot camp again after doing hundreds of push ups

for no apparent reason, other than for the sardonic

pleasure of the TI. I think Dave Nichols has the right

idea about using the power plane.

|

|

About halfway through the stack, I noticed that

I wasn't making much progress on the top sheets in

the stack. I discovered that I had my "upper

support guide" set too close, so I moved it from

6" to 9" behind the edge of the top sheet.

Then things were correct again and the bevel angle

changed to what it was supposed to be; and work progressed

towards completion. I noticed that I wasn't getting

the straight line ribbons that you should expect if

everything goes as planned (but I don't live in a

perfect world). When I got to the point where the

bevel started and stopped at the "correct"

in and out points, I still had some waviness in the

layers of plywood. Checks with a straight edge said

things seemed correct, but it just didn't look right,

so I marked those spots and did some fine tuning with

my smaller hand plane. Things seemed to improve, but

the straight edge checks said one thing and the eyes

said something else. After some futzing around, I

called it good enough. Things looked better, but I

still had doubts.

|

|

To keep from fixating on one thing and not progressing,

I disassembled the stack and flipped the sheets around

so I could sand and seal the end grain of the plywood.

But before I apply the epoxy; I add a strip of 3"

shipping tape along the scarf's upper and lower edges

to keep excess epoxy from lumping up my good work

so far. I then mixed up 1 1/2oz of SilverTip

epoxy and brushed on all that the end

grain would absorb, and it took most of it. The rest

I used to epoxy a couple pieces of scrap plywood together

to use for rail clamps. Always have something around

that can use excess epoxy products. The panels ends

were left to cure overnight.

|

|

I removed one panel set from the work platform,

and got the other set lined up to epoxy together.

I clamp down the long sheet so I can do a dry fit

to find the correct "overall length". With

the short sheet placed so it is square and "level"

with the long sheet, I clamp a stop guide at the end

to mark this location. Then I'm sure that I can again

find the correct spot to place the short sheet after

the surfaces have been coated with epoxy.

Now it was time to get out the System Three GelMagic

and join these darn pieces of plywood so I can get

on with building the boat. Scarfing is about as much

fun as building the "true and square" frame

for a traditional style of boat. I've been using GelMagic

for all my bonding needs now, and it's the perfect

product for this application. Mix it up and put in

on, and it just sits there. On the sides of things,

underneath something, or in a gap. Stuck like, Uh,

glue.

The last time I had gone to the hardware store (my

local "Do It Center") to look for a new

3" putty knife to use to fair in the edges along

glass tape; I came across a "pointed toothed"

plastic spreading tool. Hum mm, how will this do with

epoxy? Great! I spread the GelMagic on the two scarf

faces and the toothed spreader (smallest teeth 1/16")

gave me a perfect and even coat along both surfaces.

I didn't have to worry about dripping thickened epoxy

running off either of the surfaces; even the one I

had to turn over.

Then a check to see that the short sheet was lined

up back in it's proper place, and a straight edge

check of the mating edges. Then a layer of plastic

sheeting, topped with a "true" and straight

backing plate, and a layer of sand bags to hold everything

down. Time to cross my fingers and wait until the

epoxy cured overnight. Then do it again with the next

panel pair.

|

|

After the dust had settled so to speak, I removed

the shipping tape (with the excess epoxy I didn't

have to scrape up) and looked at my handy work. Better

than the last time, but not as good as the next. As

I said at the start of this story, scarfing is an

acquired skill, and to swim you to have to get in

the water. I did some touching up to the exposed scarf

tips, and added a layer of 3" glass tape to the

inside seams of all the panels. On the outside the

bottom panels get a layer of glass, and all the panels

are strengthened by the EZ-Fillet

and three layers of glass tape (two inside, one outside)

at the keel and chine seams. The top of the side panels

are stiffened by the rails. I've also changed the

way I layout the panel pairs on the lofting drawings,

so the bottom and side panel's scarf seams don't align

with each other. That holds true now for my multi-panel

designs; everything stair steps except the bottom

keel pair.

|

|

I didn't get enough GelMagic near the outer edges

of the scarf seam, and had a couple of gaps. But after

cutting out the panels, I had good fill along the

exposed interior cut faces of the edges. To reach

maximum strength, the very outer lengthwise ply, needs

to be as continuous as possible across the scarf joint.

A person might be able to get this by hand, but I

think that only a CNC machine under controlled supervision

could achieve this in the real world. A stressed (I

mean really bent) scarf joint will always break along

the outer seam; because of the discontinuous outer

lengthwise ply caused by the cut across it's face.

A layer of glass cloth (4 to 8" wide) added to

the outer and inner scarf seams will increase the

surface strength of the plywood for our real world

needs, and can be easily hidden by a good fairing

job. My best advise is don't sweat all the little

details, just get on with it. Build your boat the

best you can and go have fun. Don't worry about what

others say. "Only he who has built a boat can

row the first mile". Heard that somewhere; Chuck

maybe. ;)

|

|

Please read Dave Nichols fine article

on scarfing after reading this story. He makes many

good points on the art. I will go to beveling only

one panel at a time on my next hull. I believe it

will give me greater control over the process, and

not have to worry about messing up sheet A if I make

a mistake in the stack on sheet B, C, or D. Adding

a power plane to my tool budget looks like a good

thing too. :) The best advise I can give is to take

some scraps and practice, practice, practice on your

scarfs, and to find the way that satisfies you! The

more you do, the better you will get.

I'm going to stop here with this part of the story.

Many of the little details about this boat's construction,

have been covered in other boat building articles

by me in the links that Chuck adds to the bottom of

this page. My next installment will probably concern

figuring out the angles and cutting the material for

the corner blocks. That has been a head banger at

times.

Check out my new flickr account for this boat; it's

link is https://www.flickr.com/photos/10ftnuthatch

I will be adding more photos as the construction progresses,

so come back often.

Thanks again for reading my stories.

Warren Messer

Red Barn Boats

On

to Part2

Other Articles by Warren Messer

|