|

Obsolete Outboards |

|

| by

Max Wawrzyniak - St Louis, Missouri - USA

Bringing

a 1956 Johnson 15 hp Back to Life

Part

V: Carburetor

Work,

and a Few Words on Fuel |

|

Part

1 - Part

2 - Part 3 - Part

4 - Part 6 - Part

7

Although we had the magneto ready to reinstall last

month, I usually suggest that one wait until the carburetor

(carb) work is done before reinstalling the magneto.

Although the carb can certainly be removed and reinstalled

with the magneto on the engine, leaving the mag off

gives one a bit more room to work.

Before we get into the carb, however, we need to discuss

some late-breaking developments in the gasoline situation.

As most residents of the USA are probably aware, refineries

are discontinuing the use of an gasoline additive

known as MTBE in favor of another additive known as

ethanol. The August/Sept. issue of Professional Boatbuilder

Magazine has a very cryptic article concerning the

problems that this "reformulated" gasoline

is causing in both old and new marine engines. As

of this writing (Sept. 2006) this issue of Pro. Boatbuilding

can be accessed online HERE.

(if there is a newer issue showing,

try the "Archives" for the Sept/Oct 2006

issue - Ed)

A quick summary of the problems that reformulated

gasoline containing ethanol is causing in boats: The

ethanol is literally dissolving fiberglass fuel tanks,

which had previously been considered to be a high-quality

alternative to corrosion-prone aluminum and steel

gasoline tanks. Some very expensive production boats

built by top-line builders may require very expensive

tank replacement. Plastic tanks, such as the common

portable tanks used with outboard motors, are fine

as long as they are in good condition.

|

No caption

needed.

(click

images to enlarge) |

|

Another problem is that the ethanol can absorb a

very large amount of water, and if the water is allowed

to settle to the bottom of the tank and then drained

or pumped out, the ethanol component of the gasoline

will stay combined with the water and will also be

removed from the tank, leaving one with gasoline that

is missing a major part of it's chemical make-up.

The article mentioned suggests that one ALWAYS use

a non-alcoholic fuel stabilizer, at ALL times. Gasoline

now just does not have the "shelf life"

that it used to, so try to avoid storing gasoline

for months at a time and always protect the tanks

from water intrusion while being aware that the ethanol

can absorb humidity from the atmosphere as well.

And it is getting more difficult to check for water

in one's gasoline tanks. For years I have advocated

the use of "water finding paste;" one smears

a bit of the paste on the bottom of a stick, pokes

the stick into the gasoline tank, and if the brown

paste turns purple, there is water in the gasoline.

I have been using the same tooth-paste-size tube of

"Kolor Kut" water finding paste for over

15 years (no kidding !) but have now been informed

that it will not detect water combined with ethanol.

I now need to buy a new tube of Kolor Kut especially

formulated to detect water in ethanol-laden gasoline

(figure SF 32).

Ethanol is dissolving varnish and other "gunk"

that was once considered to be more-or-less permanent

in the fuel system, resulting in plugged fuel filters

and plugged carbs. It is more important than ever

to have good fuel filters and water separators in

one's fuel system. My habit in the past was to utilize

the glass-bowled filter/separator that was usually

factory equipment on old OMC outboards, and in addition

to install a clear plastic "in-line" filter

in the fuel line under the engine cowl. Time will

tell if I need to modify that arrangement. I should

add that I always carry spares for the disposable

in-line filter. Try to start out with as clean a fuel

system as possible.

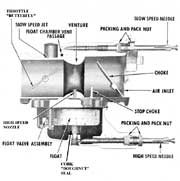

| Plugged passages

are the most common problems one will encounter

with carbs. |

|

|

It should go without saying that all fuel hoses

should be replaced. This means the hoses under the

engine cowl as well as the hose to a remote tank.

And the use of a rebuild kit for the carb with new

gaskets is always a good idea. The Sierra brand carb

kits I usually use also come with a very nice set

of instructions (figure SF 36).

A question still unanswered is how ethanol will affect

the varnish coating on the cork carburetor floats.

For the time being I intend to "run the gas out"

of my engines when done boating for the day in order

to minimize exposure to the ethanol, although running

the gas out does not totally drain the float bowl

of fuel.

One more note: in the column

on converting outboards to use a fuel pump instead

of a pressure tank, I recommend the use of a hard-setting

gasket sealant for sealing passages that are not needed.

I have a report from a reliable source that the gasket

sealant dissolved,

possibly due to ethanol exposure. Apparently J B Weld

will hold up to the ethanol better, but might make

a later conversion back to the pressure tank more

difficult, if that is a concern.

Getting back to the job at hand: The carb is held

on by (2) nuts, but before you loosen the nuts have

a look at the linkage from the carb throttle "butterfly"

shaft up to the magneto plate. When you twist the

"twist-grip" throttle, you are actually

rotating the magneto (stator) plate back and forth,

which advances and retards the ignition timing. This

action alone will cause the engine to speed-up and

slow down, and I have a few very old outboards where

advancing and retarding the magneto timing is the

primary means of "throttling" the engine.

The engine will run smoother and more efficiently,

however, if the flow of fuel and air mixture to the

engine is varied to match the needs of the engine

at a particular throttle setting. To accomplish this,

most of the older OMC outboards of less than 35 hp

have a sheet metal "cam" or "ramp"

on their forward side which moves a "follower"

that opens the throttle butterfly though a linkage.

On some engines, this linkage of levers and bell cranks

is attached entirely to the carb and one need not

mess with it when removing the carb. On other models

it will be necessary to disconnect the linkage in

order to remove the carb. On these latter engines,

usually loosening a set screw on a bell crank, or

removing a tiny cotter pin from an arm, will disconnect

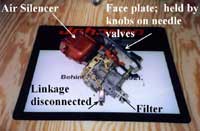

the linkage. Figure SF 35 shows where

I disconnected this linkage on the 1956 15 hp Johnson.

Another item needing to be removed is the fuel hose

to the carb from the fuel pump, or from the "quick

connector" on pressure tank engines.

|

A less

"cluttered" look at the typical

carb found on old OMC outboards.

|

|

The 1956 Johnson has a "face plate" over

the front of the carb that is held in place by the

knobs or levers used to turn the high - and low speed

needle valves. Similar vintage Evinrudes did not have

this separate face plate. Later model engines with

the "one-piece" fiberglass hoods will have

other arrangements of knobs and/or levers for controlling

the high- and low speed needle valves, and engines

manufactured after about 1963 will have a low speed

needle valve but the high speed needle is replaced

with a fixed "jet " (orifice ) that is not

adjustable. To remove the carb from a particular engine

may require you to disassemble some or all of these

linkage arrangements. Be sure to take good notes and

maybe a few photos to help when it comes time to reassemble

everything. Once this "gingerbread" stuff

is out of the way, the carbs are all really very similar.

On the '56, I was able to remove the carb with the

face plate and the air silencer intact as shown in

figure SF 37. The air silencer is

sometimes mistaken for an air cleaner but very few

old outboards were fitted with air cleaners. Just

a side note here: a modern outboard fitted with fixed

jets, when run without the restriction of it's factory-fitted

air silencer, can get too much air and run lean and

hot. Don't run modern outboards with the air silencer

removed, unless the carburetor has been "re-jetted"

to handle the extra air flow.

All we are going to do to the carb is to clean it,

replace a few parts and gaskets, check and adjust

the "float level," and put it back together.

Most of the things that can go wrong with the carb

involve "clogg" in the tiny passages through

which the gasoline must flow (figure SF 33).

This cleaning takes me about 10 or 15 minutes: if

you haven't done it before it might take you twice

as long.

| A carb fitted

with a high speed fixed "jet"

or orifice instead of an adjustable high

speed needle valve. The low speed needle

remains. |

|

|

The first thing I do is to unscrew and remove the

high-speed and low-speed needle valves (if your engine

is about a 1964 or newer model, you will only have

a low-speed needle and a plug were the high speed

needle would be - remove the plug)( figure SF

35). Note that there are threaded sleeves

that surround the needles that can also be unscrewed

and removed. These are the "packing nuts,"

and behind them is the "packing", which

are tiny rings of gasket material. Tightening the

packing nuts compresses the packing against the needles

themselves and the carb housing and seals the needles,

much as a packing gland or "stuffing box"

seals an inboard boat's propeller shaft or the valve

stem of an ordinary water valve. Remove these

packing nuts and if you can "fish out" the

old packing rings that's fine, and if you can't easily

get them out that is fine as well.

Next I invert the carb and remove the (5) or so screws

that hold the float bowl (bottom of carb) on. Once

you have the float bowl off, keep the carb upside

- down and carefully remove the hinge pin for the

float, the float itself (looks like a doughnut, and

probably made of cork unless a plastic replacement

has been installed at some point). Also remove the

float needle valve which sits underneath the float

arm. If you happen to turn the carb right-side up

with the bowl off, this needle valve will probably

fall out. Also note that the "seat" that

the needle valve fits into is made of brass and is

removable if you have a "regular" screwdriver

with a very wide blade. Since you are following my

advice and using a rebuild kit which includes a new

needle and seat, you ought to try to remove the old

seat. If you strip the tiny slots on that brass seat,

however, you have a problem. I have been able to remove

these, without the proper wide-blade screwdriver,

by using (2) small regular screwdrivers braced against

each other in an "X" pattern, with the blade

of each driver engaged in opposite sides of the slot.

If you tear-up the seat trying this, it aint my fault.

See figures SF 35 & SF

38 for a look at the parts you will be dealing

with and their locations inside the carb.

|  The

Sierra kit that I used on the 1956 Johnson

15 hp, part # 18-7043. This particular

carb kit fits several different of OMC

outboards and contains extra parts such

as gaskets in various sizes that were

not used on the 15. This kit includes

a nice set of instructions with great

drawings. The

Sierra kit that I used on the 1956 Johnson

15 hp, part # 18-7043. This particular

carb kit fits several different of OMC

outboards and contains extra parts such

as gaskets in various sizes that were

not used on the 15. This kit includes

a nice set of instructions with great

drawings.

|

|

While the carb is still upside down the final object

to remove is the high speed nozzle with is usually

threaded into the center of the top half of the carb

body. Note that there is usually a cork "doughnut"

seal around this high-speed nozzle (do not confuse

the high-speed nozzle with the high-speed needle valve

or the high-speed fixed jet we have already discussed.)

You can now safely turn the carb body right-side up

if you so desire.

You will note little "welch" plugs (similar

to tiny freeze plugs) plugging various holes in the

body of the carb. These are to close the holes formed

when the carb's inner passages where drilled. The

manuals will tell you to remove these welch plugs

(which destroys them) in order to property clean passages

behind, and then to install new plugs, which are included

with the rebuild kit. I almost never remove the old

welch plugs, as new ones are hard to get properly

sealed without the special tools for installing them,

which I don't have. (bet you don't either.) Old manuals

also generally recommend soaking the carb body in

carburetor cleaner, which is also something I rarely

do. I generally use an aerosol carb cleaner, which

is what is generally recommended for the mostly plastic

carbs found on late model outboards. Aerosol cans

of carb cleaner always come with a long thin tube

for shooting cleaner into tight places, and I generally

spray cleaner into all of the carbs openings in addition

to giving the float bowl a good bath to remove any

accumulated sediments, and that is usually enough

to clean most carbs, although I occasionally run across

one so encrusted that soaking in carb cleaner for

a couple of days is required.

A word of CAUTION: If you spray cleaner

into a little passage on a carb, it will invariably

shoot out of another passage right at your face. Wear

chemical protection goggles at a minimum! A full face

shield is better, and rubber gloves will kept the

stuff off your skin - it burns something fierce!

You have been warned.

By the way, carb cleaner removes "varnish,"

and if you have a cork carburetor float it is coated

with varnish, so don't let the cleaner get near a

cork float.

The

carb on the 15 can be removed with the face

plate and air silencer intact although you

can certainly remove these items before

removing the carb if you wish. Depending

on exactly which model of old OMC you are

working on, you might need to remove other

types of hardware, although underneath it

all the carbs are remarkably similar. The

carb on the 15 can be removed with the face

plate and air silencer intact although you

can certainly remove these items before

removing the carb if you wish. Depending

on exactly which model of old OMC you are

working on, you might need to remove other

types of hardware, although underneath it

all the carbs are remarkably similar. |

|

With the carb clean, you are ready to reassemble

(this is going purty quick, aint it?). With the carb

body again inverted (up-side down) you can screw in

the new brass seat for the float needle valve - note

that there is a little gasket that goes underneath

it. The needle valve itself just sits down in the

seat but if you check your rebuild kit carefully you

will probably find a tiny little wire "hair pin"

looking thing. This snaps onto the needle valve and

slides onto the sheet metal hinge arm of the float,

so that when the carb is right-side up, the weight

of the float (and not just fuel pressure) will pull

the needle valve down to the open position. Your old

needle valve may not have had this little hair pin

attaching it to the float.

Next you can install the float by sliding it's hinge

pin in - be sure to put the float on up-side down

(the carb is also up-side down, remember?). Next comes

checking the float level setting.

With the carb upside down, and the float all the way

up (which is actually down, since the carb is upside

down) the top surface of the float (bottom when upside

down) should be flush with the bottom edge (top edge

when upside down) of the float bowl.

"Say what??" Yeah, I hear ya; have a look

at figure SF 39: One picture can

explain it better than I can say it. The Sierra carb

kit instructions usually also have a good drawing

showing this. You make any necessary adjustments by

bending the sheet metal hinge plate on the float (I

have always said that these old outboards are "low

tech," haven't I?)

|

The carb

disassembled as far as needed in order

to clean it and install the new parts

contained within the kit.

|

|

Screw the high speed nozzle back into the center

of the body in the center of the float, and CAREFULLY

push the little cork ring seal over the nozzle.

You can now screw the bottom of the float bowl back

on, using the new gasket included in the kit (the

kit, intended to fit several different carbs, may

have extra gaskets and parts not needed for your particular

engine, so in this instance having "extra parts"

left-over when you are done is not necessarily an

indictment of your mechanical skills).

You can now insert new packing rings into the threaded

holes for the high-speed and low-speed needles (if

you were able to remove all of the old packing, use

(2) or (3) rings; if you left the old packing in,

as I do, try adding just (1) new ring of packing.

Carefully screw the packing nuts on just a bit (don't

tighten them down yet) and then carefully screw the

needle valves themselves in. You have to be VERY careful

that you do not "bottom-out" the needle

valves on their seats, as the needles are soft brass

and if their pointy ends are damaged even a little

bit, the engine is not going to run well. GENTLY screw

the needles in until they BARELY bottom, then back-off

one turn. NOW you can tighten down the packing nuts,

which will greatly increase the drag on the needles

(making if difficult to know if the needles are bottomed-out,

which is why we did not do this first.) The packing

nuts should be tight enough so that the needles take

a bit of effort to turn, so that they will not vibrate

and change their settings when the engine is running,

and so that there will be no air or fuel leaks around

the needles. One potential danger here is that a ring

of packing might get underneath the point of a needle

valve and block the passage, so use some care.

| Setting the

float level consists of nothing more than

bending the sheet metal hinge tab for the

float until the surface of the float is

level with, and parallel to, the rim of

the carb body. Make sure, however ,that

the new bowl needle and seat are in place

before you start bending. |

|

|

The carb is now ready to go back on, and reinstalling

the carb and the magneto will be next month's topic,

as will those little cyanide capsules.

Happy Motor'n

Later,

Max

click here for a

list of Columns by Max Wawrzyniak

|