|

In

Part II of this series of articles on

the design and construction of the sharpie skiff, Nemah,

I detailed how various structural "sub-assemblies"

can be combined to produce a boat that is both strong and

lightweight. Here in Part III, we will consider plywood

composite bonding techniques, and then go through the actual

process of fabricating a plywood "shell" for Nemah.

Plywood Composite

Variations

There area variety of plywood boat construction systems

that utilize fiberglass tape-bonded joints* Some are actually

plywood "plank on frame" structures that utilize

taped seam joints to eliminate the tricky bevels of chine

logs or seam battens, but are otherwise made up of frames

and other structural members. At the opposite end of the

spectrum are hulls that could be classified as "cold

molded structures fabricated from pro-bonded sheet stock,"

the difference being the degree to which the designer has

relied on the plywood shell itself to cany the structural

loads of the finished boat. Neinah falls near this end of

the design spectrum, while the smaller Constant Camber structures

carry the concept to its logical conclusion.

Bonding Techniques

The goal of any bonding

process is to create a joint that duplicates the structural

characteristics of the materials to be joined. In the case

of plywood composite structures, we want to design a joint

that is as stiff and as strong as the plywood, but is not

so stiff that it would cause the plywood to fail near the

joint by concentrating all the bending loads at one point.

To accomplish this, we will utilize two materials: epoxy

saturated fiberglass tape which supplies the needed tensile

strength; and a fillet of epoxy, wood flour, and colodial

silica which supplies compressive strength as it forms a

radius on the inside of the joint to which the fiberglass

tape will be bonded.

Figure 1- Section Through Chine

In this type of construction,

if the inside and outside layers of fiberglass tape are

not held far enough apart, or if the inside or outside radiuses

of the joint are too small, the fiberglass tape can flex

and fail. A typical plywood composite joint is shown in

Figure 1. Note how the layers of fiberglass tape are feathered

out, reducing the concentration of bending forces.

Fabricating The Shell

As we mentioned in Part

II of this series, Nemah's bottom panel

has it's face grain running across the width of the hull.

This is accomplished by scarphing several 40" x 48"

panels together, edge-to-edge, to form a single sheet long

enough to cut the bottom out of in one piece. The panel

is laid out on both sides of it's centerline at stations

measured from the transom end. This is easily accomplished

using a tape measure and framing square. After the station

points are laid out, the curves are drawn with the aid of

a wood batten stapled directly to the panel face. Cut the

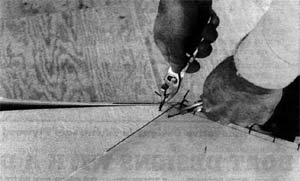

panel out using a jig saw or a circular saw as shown in

Figure 2. (Note: I prefer a wormdrive circular saw, such

as the one shown, which is much more accurate to use, as

they are gyro-stabilized by the blade and armature turning

at right angles to each other.) Plane the edges of the panel

as necessary to smooth the curve to the line.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Cutting the Panels to Shape |

Both side panels can be gotten

out of a single 4' x 16' sheet of I /4" marine plywood.

If you are scarphing your side panels out of 4' x 8' sheets,

rip them in half lengthwise and scarph each panel separately,

as it is easier to align a narrower scarph joint for gluing.

The side panels are laid

out along their top edges. (Be sure that the panel edges

you are working from are straight, as they form the sheer

of the boat.) Stations are laid out along the edge of the

panel and lines are squared down to locate the chine line.

Once the layout is complete, with the chine, stem, and transom

end lines drawn in, the two panels are sandwiched and cut

out together.

The transom is assembled

using a solid lumber core, with fore and aft faces of plywood

(or from solid stock with its grain running up and down).

For the prototype, I used 7/8" red cedar for the core,

plywood for the forward face, and tapered strips of mahogany

arranged in a sunburst pattern for the aft face. After the

transom is assembled, it is cut to shape, the side and bottom

cuts being given the specified bevels.

Prior to assembly, all components

should be precoated with epoxy. The side panels and transom

are given three rolled coats on each side. These can be

applied in one operation, moving from panel to panel in

a cycle until they each have received three coats.

Sheathing the inside face

of the bottom panel is done easily. The fiberglass fabric

is spread out while the panel is still dry, and then is

wet out with epoxy, using a squeegee to work the resin into

the fabric. A second coat can be squeegeed on after the

first coat has had a chance to set up a bit A final coat

should be applied by roller, which will finish leveling

the weave of the fabric.

Because the outside of the bottom panel will be sheathed

with fiberglass after the hull is assembled, you don't need

to coat it with epoxy prior to assembling the boat.

Figure 3 Section Through Stem

After the precoated panels

have had a chance to cure for a day (or more, depending

on the weather), you can wash them down with warm water

to remove any wax that may have formed on the resin as it

cured, and then sand the panels. Sanding can be done with

either a random-orbital (DA)

pneumatic sander or an electric orbital sander. If you use

a DA, an 80 grit, c-weight disc works well; if you use an

electric sander, you will want to start with 50 or 60 grit,

followed by 80 or 100 grit. This twostep procedure speeds

the operation, as the 80 or 100 grit paper will load up

quickly if used initially.

Assembling the Shell

Before we "stitch"

the shell together, the lower edge of the bottom panel must

be relieved with a router or block plane as shown in Figure

I, and the inside edges of the side panels need to be beveled

at the stem as shown in Figure 3.

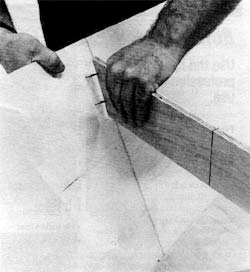

Figure 4

Once the beveling is complete,

we can proceed with the actual "stitching" process,

starting with drilling and wiring the side panels together,

as shown in Figure 4. (Note that the side panels are held

in alignment with clamps during this process.)

Figure 5

The side panels are now

inverted and spread apart 45 degrees or so. The bottom panel

is placed between the side panels and is supported on boxes

or sawhorses, so that it is easily brought into alignment

with the side panel assembly. The first two wire stitches

are then put in place, as shown in Figure 5. Note how two

pairs of pliers are used to pull the short lengths of waxed

iron tie wire up snug, prior to twisting them tight. After

the ends are given a couple of twists by hand, the stitch

is completed with two or three additional twists using a

pair of Vice-Grip pliers.

Figure 6

Because of the comparatively

thin plywood used in Nemah, it is possible to drill the

stitching holes through both the side and bottom panels

in a single operation, as shown in Figure 6. Because this

eliminates the need to work from under the shell while installing

the wire ties, the operation proceeds quite quickly.

As stitching progresses

aft (alternately working short portions of both sides),

move the loose end of the bottom panel up or down to bring

it into alignment. Position the last stitches about 2 inches

ahead of the transom end of the hull.

Figure 7

After the stitching operation

is complete, the hull can be righted and placed on low horses.

At this point the temporary spreaders are installed in their

specified positions, as shown in Figure 7. (Note the centerline,

which is marked on the spreader during fabrication.) Once

the spreaders are fitted, adjust the hull on its horses

so that the centerlines of the spreaders are in visual alignment.

The transom can now be bonded

in, being fastened in place with bronze ring nails through

the bottom and side panels. (Note: If the side and bottom

panels do not come out even in length, align the transom

with whichever is shorter, being sure to keep it parallel

with the edge of the longer panel.) After the transom is

in place, a temporary stringer is fitted down one side or

the other of the centerline of the spreaders and attached

to a block screwed to the inside face of the transom. This

stringer can be a long, straight 1x6 or a couple of 5-inch

by 8-foot plywood rippings. If plywood, they can be fitted

to either side of the centerline with one extending forward

and one extending aft. Again sight down the spreader centerline.

If it does not line up with the stem, adjust the positions

of the sawhorses to correct the misalignment.

Applying The Structural

Fillet

The "recipe" I

currently use for structural filleting has proved to be

both economical and easy to work with. It is made up of

one part colodial silica (Cab-o-sil), two to three parts

wood flour, and enough epoxy/hardener mixture to yield a

creamy peanut butter consistency. I start with about 3 ounces

of resin and add the dry ingredients, using a coffee scoop

as a measure. (Larger quantities tend to be hard to mix

evenly and can heat up on you if not used quickly.)

Figure 8

Using a 3/4" x 8"

stir stick, daub the filleting blend into two or three feet

of joint. Then, using a paddle of the proper radius (1/2"

radius for the transom and stem; 1" radius for the

chines), go back over the joint leaving a smooth fillet,

as shown in Figure 8. Remove any excess immediately with

a putty knife, as it is difficult to remove after it cures.

Continue working your way around the perimeter of the boat,

making up additional batches of filleting compound as needed.

You may have to do a little "sculpting" to fill

in at some of the corners.

After the fillet cures,

scrape or sand away any irregularities, using a radiused

block and a piece of coarse sandpaper.

Interior Taping

Because the finished joints

arc to be feathered out, it is a good practice to use a

different width of tape for each layer of the joint. For

Nemah, I used 8.5-ounce tape in 4", 3", and 2"

widths, applying the 4" width first, followed by the

3" and 2" tapes.

Precut your tapes for each

joint; including the chines, the perimeter of the transom

and the inside of the stem; allowing about 2" extra

on each end for lapping in the comers. Just prior to applying

the tape, apply epoxy to the area of the hull where the

tape will contact, paying extra attention to the fillet

itself, which is often porous.

Figure 9

Pre-wet the fiberglass tape

using a roller, as shown in Figure 9. Note how the longer

lengths are rolled up on a short length of broom stick after

wetting out. Figure 10 shows how the tape is applied to

the joint, rolling out a foot or so at a time and smoothing

it out with a gloved hand. All three layers of tape should

be applied in one continuous process, If you should have

to stop, and what has been applied sets up, you will need

to sand any irregularities and then re-wet the joints before

continuing.

Figure 10

After the interior tape

has set, brush on one or more additional coats of epoxy

to fill the weave of the fabric.

Bonding the Exterior

After the interior bonding

is complete, invert the hull and stabilize it on saw horses.

Clip one side of each of the wires down close to the plywood,

and then ease them out, using a claw hammer.

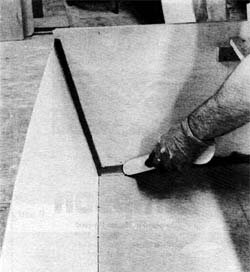

Using a block plane followed

by a sanding block, radius the chines as shown in Figure

1. Round off the bottom and sides of the transom in a similar

fashion. Take care when radiusing the stem that it remains

straight when viewed from the side. The stem heel should

be well rounded off, as it will receive quite a number of

layers of tape, and could develop a slight bulge.

After lightly sanding the

whole bottom to remove any splinters and so forth, position

the sheathing fabric and smooth it out. Wet out the bottom

sheathing with epoxy, using a squeegee, taking care not

to allow excess resin to run down the sides of the hull.

At this point you have the option of immediately trimming

the fiberglass fabric around the perimeter of the bottom

panel with a sharp utility knife or a single edge razor

blade, and then going ahead with the taping of the outside

pints; or letting the bottom sheathing cure and trimming

it afterward. If you plan to let it cure, you can squeegee

a second coat of resin into the weave as it sets. If you

do trim it after it cures, be sure to sand it to a feather

edge before

applying the outside tape.

Outside taping is essentially

a repeat of the procedure for interior bonding, except that

it is much easier to apply, owing to easier access. As with

the interior, be sure to wet out the edges of the joint

before applying the tape. Apply one or two additional coats

of epoxy to fill the weave.

Allow the tape to cure for

a day or so, and then feather sand as shown in Figure 1.

Use care while sanding to prevent excess removal of material

or sanding through the epoxy coating of the side panels.

(You need not sand the inside tape in the areas where the

fore or aft flotation chambers will be fitted) Take extra

care when sanding in the area of the radius itself: You

may want to hand sand this area to prevent sanding through

the tape. After sanding, apply one last coat of resin to

fill in any irregularities.

Next time, in the final

installment of this series, we will bring Nemah to completion,

trimming her out and fitting her rig.

Visit Tracy's website:

https://www.tracyobrien.com/

|