Custom Search

|

|

| sails |

| plans |

| epoxy |

| rope/line |

| hardware |

| canoe/Kayak |

| sailmaking |

| materials |

| models |

| media |

| tools |

| gear |

|

|

| join |

| home |

| indexes |

| classifieds |

| calendar |

| archives |

| about |

| links |

| Join Duckworks Get free newsletter Comment on articles CLICK HERE |

|

|

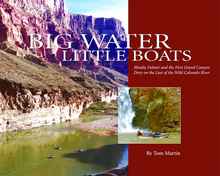

| Book Review: Big Water Little Boats |

by Tom Pamperin - Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin - USA |

This is a book review of Tom Martin’s Big Water Little Boats.

Martin, Tom. Big Water Little Boats. 240 pp. I met author Tom Martin on a rafting trip through the Grand Canyon. We had plenty of time to talk on our journey together - twenty-four days’ worth. At some point I remember asking Tom how many times he had run the Colorado River through Grand Canyon. “I don’t know,” he told me. “I stopped counting when I passed my age.” * * * The best description I found of the book’s content is in the Prologue, where the author explains that Big Water Little Boats “contains the stories of an incredibly rich array of self-guided river runners in Grand Canyon, based on their trip logs, letters, photos, and personal recollections”(12). Indeed. The book is exactly that. The story of boat builder and whitewater pioneer Moulty Fulmer is the unifying thread that runs through the book, but the picture that emerges is far bigger than one man’s story. Instead, it’s a fascinating history of do-it-yourselfers who designed and built their own boats, taught themselves how to run big whitewater safely, and all on their own, pretty much invented modern self-guided river running in the Grand Canyon. It’s that story—the story of everyday people going out and finding adventure for themselves without guides or instruction books or official certifications—that lies at the heart of the book. Tom Martin’s exhaustive research into Fulmer and his contemporaries (there are detailed end notes for any readers who might want to track down Martin’s sources) introduces readers to the world that existed before outdoor adventure had become the high-priced commodity it is today—a world with no R.E.I. stores, no high-tech gear from Patagonia or The North Face, no instruction manuals or Falcon guides. There was no “right” way to do anything but to go out and give it a try and see for yourself what would happen if you did. And what happened was the introduction of a new class of whitewater boats whose descendants still run the Colorado today. But Big Water Little Boats, as the subtitle suggests, is also the story of one man: Moulty Fulmer. Fulmer is a relatively unknown figure in the whitewater world, but Martin’s book aims to change that. After providing a brief overview of Fulmer’s early life and his career with the Muncie, Indiana YMCA, the story moves quickly to Fulmer’s growing involvement with Grand Canyon river running through the 1940s and 1950s, and his efforts to build the perfect whitewater boat. Martin makes a good argument that Moulty Fulmer was the first to introduce a decked, dory-style hull to Grand Canyon boatmen with his 1953 design Gem. Although Martin makes more of the connection between Fulmer’s Gem and today’s McKenzie River drift boats than I would (the Gem has much less freeboard, and less flare, than a drift boat, and is not a double-ender as the typical drift boat is—in short, it doesn’t look much like a drift boat to my eye), he does provide support for his claim that Moulty Fulmer was familiar with, and probably to some extent inspired by, the McKenzie River boats of the 1950s. And whether based on a drift boat hull or not, Fulmer’s innovative Gem, with its full-flotation decked hull and continuous rocker for maneuverability, set an important precedent in designs for big whitewater.

Along with tracing Fulmer and contemporary Pat Reilly’s evolution as boat designers and builders, Martin provides detailed accounts of their 1940s and 50s river runs, including an historic trip in 1957, when the Colorado River topped out at over 125,000 cubic feet per second—the highest water ever run. Here Martin’s writing is at its best, describing the river and its unprecedented power in energetic prose that puts the reader into the action, as in this passage:

Just doing the research and interviews for the book must have been a daunting task, but thanks to the quality of the writing, the result is an engaging read rather than a tedious just-the-facts accounting. Like the best history writing, the story is always present. Another feature that really brings this book to life is the wealth of historical photos it contains, spanning from the 1940s through the 1960s—most of them in full color. The originals were high quality slide photos, and the copies are cleanly reproduced, set into the text in a logical and attractive layout. The book’s format—an 8 x 10 landscape layout—works well, too. Looking at these photos is like watching a slide show about the early river trips (lots of boat pictures), with all of the magic and nostalgia of the pre-digital world brought to life for readers. The photos in Big Water Little Boats provide a welcome window into a golden age of adventure, and will be the only chance most of us ever have to see what Grand Canyon was like before Glen Canyon Dam.

Also of interest are Martin’s digressions into various other historic moments in the history of Grand Canyon whitewater: early power boat trips by Dock Marston, the first appearance of rubber rafts, a 1938 kayak expedition, and more. Martin’s obsession for comprehensive research shows clearly here—he can’t let a good story or a new development pass by without comment, though the center of the story remains Moulty Fulmer and his fellow boat designers and boat builders. Readers may be left wanting more—but that’s no tragedy. If anything, Big Water Little Boats will simply inspire further reading about Canyon history. For obvious reasons—boats, adventure, do-it-yourself experimentation - Big Water Little Boats is a good book for Duckworks readers. The evolution of whitewater boats and the techniques used to run big rapids documented here are an interesting reminder of the power of just trying something out and seeing what happens. Dragging heavy chains to slow boats down, positioning watchers on shore to signal a safe line through a rapid, continuous rocker and full flotation for whitewater hulls, even the seemingly obvious breakthrough to position the rower facing downstream—all these tactics (some still used, and some not) we owe to river runners who were not afraid to teach themselves through hard-won experience. It’s an important reminder in today’s world where we all too often reach for the latest gadget, the detailed guidebook, the careful instructions from someone who’s already done it.

The book ends with a chapter of Martin’s own involvement in the Moulty Fulmer story: in 2009, Martin built a replica of Fulmer’s Gem, taking measurements from the original hull (preserved in Grand Canyon National Park’s historic boat collection) and paying close attention to historic photographs. Martin has taken his replica Gem on four Canyon runs so far, with no plans to stop. Duckworks readers might appreciate more detail in this brief section (there are only a few construction photos provided, and no offsets or plans for would-be builders), but Martin’s vivid account of his run through Lava Falls in his Gem replica (the first time Fulmer’s design had attempted to run Lava) takes readers into a you-are-there description that alleviates any disappointment over a lack of building details:

Having rowed Lava Falls myself—most of it, anyway, before being thrown from my raft—Martin’s description rings all too true. Reading it is the next best thing to taking a place at the oars for your own run. |