|

Adventures Teach Lessons

As open water voyages go, a sixty-eight kilometer round-trip does not sound like a long way to travel. I've been much, much further on many occasions and I have a friend who repeatedly sails halfway around the globe in double-handed yacht races, without even batting an eyelid. However, even a short trip can be filled with adventure - it all depends on the sort of boat you are in, and what the weather hands out to you at the time.

Not too long ago I found myself sitting in a rented beach-house, gratefully experiencing the feeling of very hot coffee sending fingers of warmth through my chilled body, while beginning to dissect the last four days of beachcruising. Trust me when I say that being frightened brings with it a lot of associated feelings, but one of the good ones is being able to talk about it later. I don't mean bragging, but just being grateful for having pulled another one off and being able to add it to the list of worthwhile activities.

There are long-term implications, and in this case it had a direct impact on how one of my designs evolved – which is how it should be when thinking about going out on the water in small-craft, especially for those who are interested in some serious open-boat cruising.

A Few Days of Beachcruising

This had been a two-boat trip. One was a 23ft x 5ft 7in powerboat called Sharpshooter, designed by Phil Bolger (a wonderful vessel), and the other was a 12ft sailing dinghy of a little over four feet in breadth (yes, yes, I know that the crusty old salts will say I should say, beam” – but the correct term is “breadth” – as in “breadth of the main beam”). Our journey was well planned, and we had good equipment to back up the experience of the crew members.

|

23ft Sharpshooter with her modified cuddy |

The outward leg was uneventful, and we then spent a few days in a location generally only accessible by boat – good beaches, good bush land, an isolated lighthouse, plenty of oyster rocks, crabs to be caught, and fish to be grilled over a fire on the sand. It was great to see the kids engaging in all of these activities, and I know from subsequent conversations that the effects of this adventure, and others before and since, have left positive marks on their souls.

Night time found us lying on our backs staring up into a tropical sky filled to overflowing with billions of stars. The only human intrusion came from the surprisingly frequent passage of brilliantly-lit satellites, silently moving across the sky, only to blink out in an instant as they entered earth’s shadow. Three or four hours can disappear in deep conversation at times like this, and it shows just how much communication has been destroyed in our “normal lives” because of television and computers…

Those of you who are used to my writing will be saying that I’m writing more of the same old stuff – so I’d better get to the point before you slip off into a coma….

A Wild Trip Home

The point I was getting to before becoming distracted with the romantic story is that the trip back home was a bit wild. The 23-foot powerboat did fine, and so did we in the little sailing boat – but the sailing boat was too small for the conditions, and we had to concentrate fiercely to remain upright in a situation where a capsise would have had serious, and potentially fatal, consequences.

|

The 12 footer and her 14 yr old builder (before the proper sail had been made, and before the trip) |

Ironically, the plan was for the powerboat to leave slightly after us and act as a shepherd – but we were going so fast, even with a deep reef tied into the sail, that the rendezvous took place much, much further up the coast than planned, by which time the dangerous bit was over and we were just cold and grumpy – no longer scared! Had we been in a slightly larger sailing dinghy the voyage would have been a good deal less tense!

Changing the size of a boat has BIG consequences

So, what is the point of my story? It is that a small difference in the size of a boat can have a major effect on her carrying capacity and, more importantly, her stability.

Not many people appreciate that the volume, weight, and cost of a boat vary according to the CUBE of the change in dimension (assuming similar proportions). So for example if we had been in a 15 footer instead of a 12 footer, our carrying capacity would have been increased by 195%– that is nearly double for a fairly modest increase in length and breadth. But of course, a 15 footer is more expensive and heavier - if you are building her yourself it doesn’t matter that much.

Now, the really telling point is the stability. By going from 12 feet to 15 feet, the stability of the boat increases by an exponent of 4. That means that the 15 footer has an increase in stability of 244% - that is nearly two-and-a-half times more stable!

Even better, the increased carrying capacity of the larger boat means that you may choose to carry some internal ballast to make things even better. A few sandbags can have a remarkable effect, but you must remember that they will also help take your boat to the bottom if you don’t have enough emergency floatation. I choose to use water ballast – 100kg of water weighs the same amount as 100kg of sand, or lead (or feathers, for that matter). As long as it is contained in tanks or jerry cans inside the boat (i.e. not subject to free surface effect) it works very effectively. But, in a swamping, the water ballast assumes neutral buoyancy, so it won’t take you to the bottom of the ocean.

Of course the stability and volume rule also works in reverse, which is why we felt so uncomfortable in our 12 footer, on the big water with a twenty knot breeze blowing and big rollers smashing up against the cliffs on an isolated bit of coastline.

Ian’s Good-But-Small Boat

Some would say that the long highway trip home in our old Series 3 Landrover was the most dangerous part of the entire journey, and that we should have learnt a lesson from that - but those sorts of people are very unkind (yes, you know who you are!).

|

The Series 3 Landrover - interesting... |

The practical implications surfaced some time later on when my good (I use the term lightly) friend Ian Hamilton asked me to design him a new boat. Now Ian has had his fair share of boating and bush adventures, and despite my frequent ridicule of his abilities, he knows what he is doing. Among the boats that Ian has built is a gem from the board of one of the greatest small boat designers the world has ever seen.

This beautiful boat is a superb example of practical design in plywood. Her hull-shape is reminiscent of a Swampscott Dory, she rows exceptionally well for a boat of her size, and she sails like a dream. Not only that, but the internal arrangement has been skillfully worked-out to allow for one or two adults to sail her while sitting comfortably with their bottoms out of the bilge-water and their backs well supported by sides. A clever distribution of surface area between the rudder and the forward-located centerboard allow for a full-sized adult to lie at full length on the floorboards without having to twist and bend around normal protrusions like centerboard cases.

The problem is that this gem of a boat is only 11-1/2 ft x 4 feet. This is great for her role as an easily-transported dinghy, but it means that she is a very small boat indeed if you find yourself in rough water. Ian has rowed her on some serious open-water trips, and the quality of her hull design has allowed her to perform far better than one would imagine. But she is still a very little boat.

When under sail, things get a bit more tricky. In fairness to her brilliant designer, she was intended for operation in sheltered waters. But due to overconfidence combined with a lack of suitable enclosed water up around Mackay, Ian has had her out in some tricky conditions while under sail (do not try this at home…). She has no side decks, making it relatively easy to sail her gunwale under, and it is almost impossible to lower or raise her rig without running her up on a friendly beach first. It is just too difficult to keep her upright in waves when you move forward to the mast.

Adding to Ian’s problems in the small boat field is that he is getting old and decrepit (I, on the other hand, am only getting old…). Due to a troublesome hip and lower back, Ian has found it increasingly difficult to sit comfortably in his boat while rowing. This has caused him much distress, as he is serious about his rowing, and knows how to cover distance offshore.

A Wish-List Emerges

|

First Mate - Same rigs and layout as Phoenix III - different hull |

Ian came to me with a request for a new boat and he provided me with a wish-list (always a good way to start): -

-

She needed to be light enough for him to manhandle off a box trailer (probably using a hand trolley like the racing dinghies employ);

-

The rowing position needed to be higher than in his previous boat, but the geometry had to be correct for proper rowing. In particular, the height of the oarlocks above the thwart (seat) had to be correct, along with them being the appropriate distance aft of the thwart;

-

There had to be enough room for Ian and his gear. In the previous boat he had been able to carry overnight gear and his “hunting” equipment (crab pots, fishing gear, bait, nets etc) – but not both – not if he wanted to get some sleep towards the end of the night;

-

Safety in open water had to be improved, with a rig which was simple to raise, lower and stow – all while on the water. And he expressed a desire for side decks to make it less likely that he would take water over the lee-rail in tough conditions, as well as making it easier to sit out on the gunwale to hold the boat upright;

-

Ease and cost of construction had to be within his comfort-zone. Other than indicating that he was partial to the layout of my Phoenix III design, he gave me a free-hand in meeting the wish-list.

Lessons from the adventure bear fruit

One of the most powerful memories I had from the adventure I mentioned at the beginning of the article was the strong desire I felt at the time for a bigger boat! Once we were safely ashore we had convinced ourselves that all was fine, but I would have sold my second-born child for a bit more security when we were out in the blue stuff with nothing but ocean between us and other side of the inappropriately-named Pacific (the second-born was onboard with me that day, so don’t tell him about this article).

Knowing that carrying capacity and stability go up exponentially with increase in linear size, I didn’t have to design a particularly big boat to meet the requirements. I had previously designed a lapstrake sailing dinghy called Phoenix III and she incorporated the proportions and sizes which I had come to feel were a good compromise. I already knew that the rig options worked, and that the layout had proven to be a great success. Additionally, her rowing position was designed around my very best understanding of traditionally-accepted geometry, and it had worked very well in the lapstrake boat.

|

Phoenix III - Rows and sails well |

The size which I had settled on was between 15ft and 15-1/2ft (4.6 to 4.7metres) length-over-all, and a breadth of between 4-1/2ft and 5ft (1.4 to 1.5metres), and these seemed appropriate for the new design.

Simple Construction Required

The fly in the ointment was Ian’s lack of confidence as a builder. Had he been more experienced with glued-lapstrake (clinker) construction, he would have been very well served by the existing Phoenix III design. In fact, as far as clinker boats go, she is quite straight forward to build. But Ian wanted something quicker and easier, and he was already very satisfied with the stitch-and-glue method he had used on his smaller dinghy.

So, I tried to reproduce the layout and performance of Phoenix III but in a stitch-and-glue context.

A new design emerges

|

Installing the centreboard case in the first

First Mate |

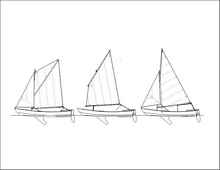

The resulting boat is a design called “First

Mate”, which I first mentioned briefly in the pages of this

magazine a bit over a year ago. At that stage the plans were complete,

but the instructions were at a very basic stage. Now the whole

lot is finished, with about 29 sheets of A3 drawings, two sheets

of A4 drawings, and a 57-page colour illustrated building instruction

booklet. Included are oar drawings, three different rigs (which

all use the same mast step and partner), and even a set of dimensions

for a simple-to-build galley box which fits under the main thwart.

Ian has his new boat design, and his own boat is nearly finished.

What is special about stitch-and-glue?

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the true stitch-and-glue building process (there are variations on the theme), I’ll give a very brief run down:

-

No strongback or station mold is required (as long as the designer has produced accurately developed hull panel shapes);

-

Very few longitudinal framing pieces, such as chines, keelsons, clamps etc are necessary. These are replaced by simple epoxy-and-glass-tape joints – no beveling required, but you do have to clean up the cured epoxy lumps and bumps;

-

The vulnerable plywood edge-grain is protected inside the glass and epoxy joints;

-

Reasonable gaps in the various joints are quite acceptable, as the epoxy/glass combination bridges the gaps with excellent structural capability;

-

Very few expensive metal fastenings are necessary. The hull is stitched together with plastic cable ties, which are removed after the first “tack-welds” of epoxy have cured. Some people leave the ties in place, but I remove them;

-

No difficult plank spiling (a black art to some people’s eyes) is required;

-

The interior of the boat is usually very clear of water and dirt-trapping frame work.

|

Proper stitch-and-glue can give a very clean

interior |

It is critical that the designer calculates

the proper weight of glass for each joint. A good designer will

have employed an engineer, or have consulted an approved set of

scantling rules. If in doubt, ask the designer how his specifications

were established – it is your life.

Suggested reading

***********

|