The pleasures of a lightweight boat are an acquired

taste, sort of like basswood Piantedosi sculls, turbocharged Mini

Coopers and McManus cabernet. There are multiple advantages both

obvious and eventually realized, but the use and ownership requirements

of a ply/epoxy lightweight gives a fresh spin to the term pleasure

boating, and it’s hard to go back to the ordinary. And although

we’re talking mostly about ply/epoxy cartoppers, many weight

saving techniques can be appropriate for larger boats.

The real advantages begin to show up not only in performance and

payload, but in getting the boat to and from launch and retrieve.

Lightweights under 100 pounds can easily be cartopped, which eliminates

the complexities, legal and otherwise, of pulling a trailer. If

you can lift 50 pounds by yourself you can handle a 100 pound

hull because you only have to lift half the boat at a time for

sliding it onto a roof rack. And even a 100 pound hull can be

carried on the smallest of compact-car roof racks, further increasing

the options for mobility. The ability to load and unload your

boat without assistance is a real convenience. For those unable

to carry, a lightweight with a slick, graphite-coated bottom can

be dragged without harm across parking lots, down launch ramps,

and over gravel beaches. Run a tether through a bow eyelet and

just start walking.

Lightweights can be faster when speed is important, or when stability

is critical they can be ballasted specifically to punch through

small chop, or enhance stability in wind. Ballasting weight can

be distributed fore and aft toward the ends of the hull, and as

naval architects like to say, this will “dampen the moment”

and reduce the hobbyhorse action of a lightweight hull. Alternatively

the ballast can be centered low and midships to aid stability.

Removable ballast is also a considerable safety factor if you

get in trouble as it’s easy to flip removable ballast overboard,

and with watertight compartments the hull will support itself

even if flooded. Whether the ballasting is lead shot in bags,

sandbags, water filled compartments, or just camp-cruising gear

and a passenger is a choice with a lightweight boat. Twenty to

30 pound bags of sand will nestle into odd corners low in the

hull where ballasting is most effective and can be moved with

one hand, leaving a free hand to hold oars or motor controls.

|

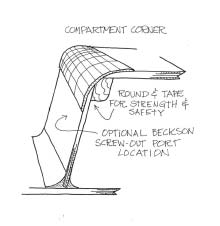

Compartment Corner |

These boats do not lend themselves to production techniques but

are ideal for the amateur builder. You can build a ply/epoxy boat

and use it for years then give it to the grandkids in about as

good a shape as when you built it. They don’t watersoak!

Maintenance is simplified and longevity is enhanced. Epoxy is

a stable undercoat which adds longevity to an overcoat of paint

or varnish and boats often last over 15 years with the original

two coats of varnish over the epoxy finish. All this on a boat

that can be taken into open water, make landings in surf and get

dragged over beaches to a campsite.

DESIGN

The design process and preparation for building should be a period

of contemplation where you ask yourself how you plan to use the

boat. These choices require common sense to keep the boat as simple

as possible, and to start with the idea that perfection is attained

when there is no longer anything superfluous to take away, then

add-on wisely as you see the need. The construction of a lightweight

is as much art as science and requires the use of minimal and

strength-consistent scantlings throughout the boat in order not

to add unnecessary weight by over building. Here's where you can

push the envelope a bit, but common sense and safety are still

the prime requirements.

Two opposing options are to build the hull with a thicker skin

and minimal internal framing, or to go with a very thin skin and

rely more on internal framing, and it really depends on how you

plan to use the boat. Camp-cruisers, river boats, and drifters

dealing with rocky bottoms and beach landings obviously need more

abrasion protection than a boat launched from a pier and used

only in deep water. Building and installing all the fussy little

parts that make for internal bracing also makes for a more labor

intensive hull, but it can be the lightest way to go. All interior

components should also be designed monocoque with everything fastened

to everything else, which is also easy to accomplish with ply/epoxy.

Compartments are the structural furniture of these boats and can

easily be made into seats, live bait wells, foam lined iceboxes,

dry gear lockers, and are also handy to isolate fuel tanks, batteries,

food, etc. Installing truly watertight bulkheads and decks is

a piece of cake with ply/epoxy and compartments can easily be

added throughout the hull and accessed with plastic screw-out

ports or hinged hatches. Self-bailing capability can be arranged

by diverting all water aboard to drain into a single footwell.

Emergency flotation capability is perhaps the coolest byproduct

of compartmentalization and makes an appealing safety feature,

and if the hull is sensibly compartmentalized both fore and aft

to maintain trim, the hull can fill from a sloppy wave top and

you can keep right on rowing, motoring, or sailing.

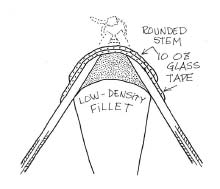

With ply/epoxy there is seldom need for the timber stem pieces,

chine cleats, and transom framing used in traditional construction.

To build a lightweight stem, stitch the port and starboard panels

together at the bow and apply a large interior fillet. Remove

the ties, and round and tape the stem exterior. Large radius rounds

are more durable than small rounds. For extra support apply a

second strip of narrower glass tape to stagger selvage edges.

To add support a number of four mil plywood cant frames can be

installed extending 90 degrees off the stem angle, and all this

can be further reinforced by adding a compartment in the forward

part of the hull. Stems built this way become very durable.

|

Rounded Stem |

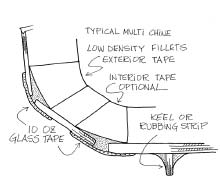

A curved panel is much stiffer than a flat panel and shape can

be used to provide strength without penalty of added weight. Round

bottom and multi-chine hulls function with minimal internal framing,

and the intersection of panels on multi-chine designs is reinforced

with epoxy fillets and glass tape to become a fore and aft “stringer”

which provides resilient stiffness the length of the hull. Even

on single chine hulls the tape and epoxy fillet forms an I-beam

structure that extends strength between athwartships supports.

Apply tape both inside and multiple lams outside for added strength.

|

Typical Multi Chine |

Ply/epoxy construction allows the use of surprisingly minimal

thickness components. There is seldom a structural need for vertical

bulkheads thicker than four mil in these cartoppers, and flat

and sloping decks in lightweights can usually be four mil “no-step”

decks, or an upgrade to six mil in decks used for seating and

glass cloth can also be applied to decks vulnerable to wear. Decks

provide two-dimensional hull support, and no underside support

cleats are required when a deck is filleted into a sloping hull

side. A large radius fillet will reach out onto the deck two inches

or more providing an attractive structural molding; any hatches

or screw-out access ports will also stiffen the deck. Compartment

edges are fitted with a softwood cleat on the inside edge which

serves as a glue surface for the deck, and after gluing down the

deck a large diameter round is cut into the edge and taped.

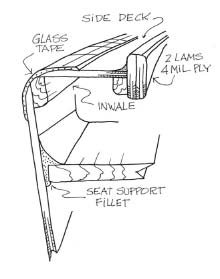

Side decks are an overlooked method of reinforcing the sheerline

of the hull with minimal weight. When adding a side deck it’s

possible to eliminate all but a single inwale glue strip and after

attaching the side deck take a block plane and cut a large radius

round on the edge of the hull, then apply glass tape for a clean

“sneaker” look that will take a lot of abuse.

|

Side Deck |

Four mil ply is sufficient for narrow side decks, but larger,

wider decks may need six mil ply. Glue on a flexible laminated

plywood coaming for extra support and to help keep the cockpit

dry.

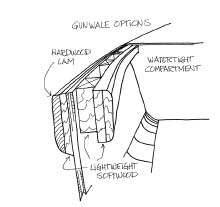

The gunwales or sheer line of these small boats deal with terrific

stress from rowing, wave action and the grinding abrasion of laying

against gnarly pilings and alongside other boats. My own boats

are routinely flipped upside-down for storage and rolled over

on their side to form a windbreak or rain shelter for camp-cruising.

Multiple strips are laminated onto the plywood sheer line of the

hull to form the gunwales, and hardwood strips look and wear better

but are much heavier. Lightweight softwood can be used for dramatic

weight saving, or use a single strip of hardwood over softwood

lams. To add more stiffness separate the inwale and outwale strips

with lightweight spacer blocks, or to reinforce the ends of the

hull more efficiently a compartment with flush deck provides useful

space, and the gunwale structure can often be shortened or eliminated

between compartments.

|

Gunwale Options |

I always encourage builders to climb inside the hull as soon as

possible during this process for trial fitting before deciding

the final location of seats, compartments, oarlocks, foot stops,

etc. Stack phone books for seats, clamp-on temporary oarlock positions,

use blocks of wood for foot stops and so on until the spaces feel

right, because we’re all built different and possess various

degrees of flexibility and comfort levels. When the hull is watertight

go out in wave action and sit quietly. Some flexing is expected

but any section of hull that pants more than a small amount may

require reinforcement and fortunately there are multiple options

to correct any problem including the addition of compartments,

glass tape, veneer patches, etc., and a real beauty of this system

is that modifications and retrofits are easily applied as needed.

TECHNIQUE and MATERIALS

Lightweight construction requires quality materials. Here's where

you pay more for less but the benefits are realized on many levels

including ease of building, looks, and longevity, not to mention

the safety factor and resale value.

Start with dry wood. Dry wood is stronger and has superior abrasion

resistance with reduced potential for rot pockets. A wood stove-heated

shop is ideal as it acts as a dryer to reduce and stabilize the

moisture content of wood. Even a preliminary sorting of materials

will produce a weight saving, so select all trim wood for optimum

grain orientation and moisture content. Keep a supply of Starbucks

gift cards in your wallet and be prepared to bribe the guys at

your local lumberyard so they’ll let you pick through the

stacks for the lightest, clearest, knot-free pieces.

Get the best plywood you can afford. Hardwood ply should be your

first choice because it takes epoxy so nicely and is readily available

in metric thicknesses and a selection of species and quality grades.

The more lams of veneer in a panel the better, and for my own

small boats we use mostly four mil and six mil British Standard

6566 or BS1088 hardwood ply. It comes in millimeter thicknesses,

and for non-metric users the six mil is five laminations of veneer

and equivalent in thickness to a hair under one quarter inch.

The four mil ply is three lams and just under 3/16 inch. Okoume

plywood is typically as much as 25% lighter than mahogany ply

and therefore a good choice for ultralights and lightweights,

but it often has somewhat less attractive grain. The topsides

in my lightweights are usually four mil, and I seldom have reason

to use anything thicker than six mil, even on white water dories

for commercial use in the Grand Canyon, some of which are still

around over 15 years later.

Ultralight hull bottoms can be as thin as four mil, cloth sheathed

on both sides and often with wider than usual tape on the chines

and graphite on the bottom exterior. For a standard lightweight

bottom, six mil hardwood ply with six-ounce glass cloth on both

sides works well, but for hard service drifters and river boats

I sometimes use 3/8 inch thick softwood AA marine grade ply for

the bottom panels. All softwood ply requires glass sheathing on

all surfaces, otherwise the swelling and shrinking of the annular

rings in softwood veneer will produce hairline cracks in the epoxy

coating. Skegs, keels, and rubbing strips can also be used to

reinforce bottoms with minimal weight and can easily be retrofitted

if needed. Skegs and keels are intended sacrificial, usually made

of four and six mil ply attached and supported by low density

fillets—all of which is easily planed off and replaced when

they wear down as intended.

An epoxy glue joint is lighter and more efficient than mechanical

fastenings, and screws are used only for temporary awkward clamping

situations or hardware installation. Screws used repeatedly are

stainless steel square drive Robertson head which do not strip

as easily as a Phillips or Reed Prince. Wax the screws with beeswax

to prevent the epoxy locking them in place and preventing withdrawal

and use flat washers to prevent burying the screw and splitting

out.

Veneer can be used for laminating very lightweight structural

knees and stems, but only slice cut, quarter sawn veneer, and

never the cheap rotary peeled veneer. Slice cut red cedar veneer

is particularly good because it is very lightweight and glues

so well with epoxy. A supportive knee laminated with three or

four lams of red cedar is amazingly strong and flexible. Patches

of veneer can also be glued to specific locations for reinforcement

or to dress up an area.

PRE-FINISHING

It’s not practical to completely “mummify”

an entire boat in epoxy, although some builders get close, but

by pre-finishing separate components before assembly it’s

possible to efficiently apply two or three very consistent coatings

of epoxy to all plywood surfaces. Pre-finishing components does

a dramatically better job than trying to coat all surfaces once

the hull is assembled. Pre-finishing ensures that all surfaces

are uniformly sealed including traditional rot pockets like the

inside of compartments, but the major advantage is that after

assembly the hull requires only minor detailing and preparation

for varnish or paint. This is huge if you consider for a moment

the usual time spent finishing.

Lay the plywood pieces flat on a workbench and dump mixed epoxy

on the plywood, move it around with a squeegee to wet the surface

then use a foam roller to achieve a consistent coating. Finish

by tipping off with a disposable foam brush. Bend down and slight

low across the surface to see globs and runs that need more brushing

or rolling. To prevent the usual bubbles in the first coating

of epoxy play the temperature game by heating the wood thoroughly

beforehand, then to prevent outgassing turn off the heat and allow

the temp to start dropping when applying the first coating. This

really works and saves time, epoxy, and effort. Let it cure overnight

and use a sharp flat scraper to remove bubbles, the usual raised

splinters and kamikaze bug craters, then apply the second coat

which will lay on much smoother.

These boats can be built with a bare minimum of tools and the

only thing you really need is a jig saw, block plane, a drill,

and various clamps, but scrapers deserve special mention. Nothing

else works nearly as well on epoxied surfaces, and don’t

even think about using sandpaper except possibly on trim wood.

A rectangular scraper provides eight cutting edges and can be

sharpened in minutes. They don’t make dust, they level high

spots and highlight low spots and can also be used to remove the

raised selvage edges of tape, and are perfect for the pre-finishing

process.

|

Car topping boat, light and stong. |

FILLETS

A fillet is a bead of thickened epoxy applied to a hull seam

or an intersection of panels, usually formed into a concave shape

by dragging a round shaped plywood paddle over the epoxy bead

before it kicks. The tenacity of an epoxy fillet is remarkable!

They become structural and also function as a supportive cleat

and molding and by using appropriate fillers they can be engineered

to match the strength of wood. Mixtures of low density fillers

such as West System 410 Microlight and 407 Low Density are ideal.

Nothing is gained by adding the considerable weight of a heavy

filler when a lightweight low density mixture will work better

and provide improved resilience to prevent cracking when flexing,

and also remain sandable if necessary.

Fillet paddles with a radius from ? inch to 10 inches will all

be useful and are easily made from scrap plywood. Tight acute

angles require smaller radius fillets and more open angles require

much larger radius fillets. Paddles can also be leaned at an angle

to increase the radius slightly, and flexible plastic paddles

can also be squeezed to fit the application. When applying large

radius fillets it may be necessary to make it a two or three step

process to get it right. Make successive passes and clean off

the excess with a sharp putty knife and then leave it alone. Don’t

pester the fillet! Sanded fillets somehow always look amateurish.

If you must sand fillets at least have the decency to paint over

them.

FIBERGLASS

The entire hull can be sheathed with six-ounce glass cloth for

additional protection, but it’s usually not necessary if

using quality hardwood ply. I prefer to tape exterior hull seams,

but if cloth sheathing is judged necessary for a yacht-quality

finish consider taping the interior seams in addition for strength.

Glass tape adds terrific strength to the hull, and I’ve

even learned to appreciate the look, but use real 10 ounce tape

and don’t cut strips from cloth as there is no selvage edge.

Apply the tape in full length strips, and use the narrowest tape

that will do the job. Tape can be applied pre-saturated or use

tabs of masking tape to hold it in position while rolling or stippling

with a bristle brush. Cut the brush bristles down to about one

inch long to provide necessary stiffness. After the tape is saturated

go to each end and tug gently to pull out wrinkles, then position

the tape over the seam by pushing with the stipple brush. Plastic

squeegees are also handy for applying glass cloth and tape as

they remove excess resin that may cause the fabric to float and

leave an inconsistent surface. Stand back often to eyeball and

correct unfairness. To add multiple layers of tape apply a narrower

width over wide tape to stagger the selvage edges. Lastly you

have the option of sanding with successively finer grits of paper

to featheredge the tape for a yacht finish, which is not my idea

of a good time, or if the hull is to be painted out use low density

sandable fillers then sand lightly. Otherwise just roll on two

coats of good varnish and enjoy the natural wood.

GRAPHITE

The use of graphite has been one of the most successful treatments

for my own series of small boats. A graphite coating provides

substantial abrasion resistance allowing a lightweight hull to

slide easily over gravel and parking lots without damage. The

more it’s used the slicker the graphite gets and adds only

ounces of weight, and may also be wrapped up around the chines

of the hull to provide an appealing waterline. A serendipitous

benefit of having a graphite bottom is that the wear pattern reveals

unusual areas of stress or wear on the bottom, which can be a

clue to retrofit a patch of glass tape to the area for reinforcement.

To give the graphite coating more body to fill small scratches

or dings mix in a small amount of colloidal silica. Spread with

a squeegee, then use a foam roller and finish with a throwaway

brush. If it gets so stiff you can’t brush it out, you’ve

mixed in too much silica.

Carbon fiber is graphite in fiber form and for certain applications

can’t be beat, but it works only in tension mode. It’s

great for oars, masts, and spars and allows scantlings to be reduced

for dramatic weight savings. Rout a groove in a lightweight oar

and saturate with epoxy, then tamp in two or three rows of carbon

fiber. Saturate well with epoxy, allow to cure then apply low

density filler to fill the slot.

Building small lightweight masts and spars is fun work, and there

are weight reducing options not available when building larger

masts and spars. I octagon most of my small masts, both to reduce

the labor of final rounding and also because I like the utilitarian

look. To lighten the mast after shaping, rip it lengthwise with

a band saw or jig saw. Leave the blade marks alone, and use a

sharp gouge or molding plane to remove wood from the inside of

each half. Take care to leave a minimal wall thickness, then saturate

each half with epoxy and reglue. Install wiring and crumpled aluminum

foil as required. The blade marks will ensure a perfect fit when

you glue it back together, and the mast will weigh about half

as much.

So building a lightweight is easy—the challenge comes in

making the lightweight boat strong enough for safety and to deal

with real world conditions. But with a combination of thoughtful

design and quality materials the amateur garage builder can produce

a structure with strength to weight ratios rivaling contraptions

from a NASA lab, and without special tools. Sure I miss the fun

of building plank-on-frame hulls with the delightful smells of

Alaskan yellow cedar and the burnt oil fragrance of sawn teak

to which I had become addicted, but the pleasures of light weight

and enhanced performance more than justify the means.

SOURCES: Scrapers: https://duckworksbbs.com/

Plywood: https://edensaw.com/

Epoxy, glass tape, graphite, carbon fiber, fillers: https://www.westsystem.com/ss/

Epoxy, glass tape, graphite, carbon fiber, fillers is available

at https://duckworksbbs.com/

Paul Butler's Website https://butlerprojects.com/

*****

|