| High in a beautiful Blue Gum tree,

a dignified Magpie viewed the activity taking place outside a

country workshop.

The bird was familiar with this place, and with its human inhabitants,

so he showed no hesitation as he swooped down to harvest insects

from the grass just feet from two men who were struggling to winch

a small wooden boat onto a galvanised road trailer.

Now, you would think that getting a light fourteen-foot lapstrake

(clinker) dinghy onto a trailer would be a simple matter, and

so it should be. The problem was that she suffered from having

come from a mixed background.

No-one could complain about the looks of this boat – she

had the shape of a classic plumb-stemmed clinker dinghy or ship’s

boat, and she showed all the characteristics of the type –

plumb stem, burdensome hull-shape, firm turn-of-bilge, buttock

lines sweeping up to a transom stern above the waterline, external

keel-batten and prominent skeg. This boat would fit perfectly

into an Arthur Ransome novel from the “Swallows and Amazons”

series.

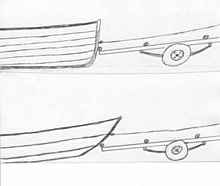

As handsome and light as this boat appeared, she was very difficult

to get onto the trailer. Why? Because her plumb stem (hyrodynamically

very efficient as it may be) would not ride smoothly up and over

the first trailer roller. So instead of the boat automatically

lifting up onto the trailer as would be the case if she had an

angled, swept-back stem, the bow came up against the trailer roller

and just stopped dead until someone physically lifted the bow

up and onto the trailer. A two-person job – one to lift

and one to winch.

|

The difference in stems. |

Not only that, but when the bow was eventually manoeuvered onto

the first trailer roller, the shape of the bottom of the boat

meant that she kept falling to one side or the other.

The problem is that many of us seem to have lost sight of the

proper application of the “form follows function”

adage. Yes, the boat’s primary function is to be an efficient

shape from a hydrodynamic point-of-view, but she also needs to

be practical in other modes of operation. Examples include efficient

utilisation of building materials, comfortable internal arrangement,

suitability for trailer loading, ease of rigging and un-rigging

– the list goes on…

The shape of boats (for general use, that is – not racing)

has evolved because of three primary influences: -

1. the sorts of materials available for construction;

2. the location and mode of operation;

3. the load to be carried.

Obviously these are not the only influences, but they are very

important. In the case of the dinghy being described, her design

goes against the common-sense application of the above rules.

She was built using the glued-lapstrake (glued-clinker) method

of construction. This is a wonderful way of building wooden boats

which will be stored out-of-water, because the glued plank overlaps

will not open up as the timber dries out in storage. Also, the

fact that glued-lapstrake produces a stressed-skin hull means

that the boat will be lighter than one of traditional construction,

further enhancing ease of loading and unloading from a trailer.

But in order for this method to work, the planking needs to be

made from high-quality plywood or some other system where cross-grain

strength in the planking is increased over what is available in

natural timber. If ordinary timber is used in a glued-lapstrake

boat, the planks will inevitably crack along the line where the

planking changes from double-thickness to single-thickness.

Plywood planks do not like being forced to take the compound

curvature that is required to produce fair plank runs in a plumb-stemmed

boat which has the beautiful hollow waterlines we find so attractive.

Some skilled designers have produced good examples, but the successful

examples still show some unfairness in the last few inches before

the stem. They also require many narrow planks rather than being

able to capitalise on the nice wide planks which can be cut from

good plywood.

|

Bolger Hope |

In the old days, when the plumb-stemmed lapstrake (clinker) boats

which we all admire were being built commercially, there were

a number of different conditions in play. Firstly, the boats were

usually left in the water (ship’s boats being an exception),

so the planks were always wet and swollen. Therefore, there was

no need for the laps to be glued to keep the water out - but the

boats did require scores of small steam-bent ribs rivetted or

clenched across the planking to provide the cross-grain strength.

Secondly, the narrow, natural timber planks were steamed in the

area where lots of twist and compound curvature was required.

The result was the beautiful sweeping plank lines which characterise

the best examples of this construction. Plywood does not respond

well to steaming, and therefore the forefoot of a plumb-stemmed

ply dinghy never quite looks the part.

So, the design of traditionally-built lapstrake boats was dictated

by the fact that they were:-

• kept in the water (no need for glued laps and no need

for trailer-friendly characteristics);

• built from narrow, steamed planking which could easily

take a compound curve.

In contrast, modern lapstrake boats should be designed with different

factors in mind: -

• kept out of water – therefore the plank laps benefit

from being glued, and the planks are best made from quality plywood;

• transported on a trailer – more easily loaded if

the bow stem is raked rather than being plumb. This is fortuitous,

as a raked bow stem is the natural termination of wide plywood

planks which have a minimum of compound curvature.

Given that the function of a modern trailerable lapstrake boat

is suited to wide planks and raking stems, lets have a look at

good-looking examples of similar boats from history. The obvious

ones which come to mind are the various Dory-styles, and the Scandinavian

Oselvers. There are others, but these will do as examples.

The Dories and Oselvers have very sharply raked bow stems and

have narrow, flat bottoms (in the case of the Dory), or very shallow

‘V’ bottoms (in the case of the Oselvers and similar

styles). Notably, both types evolved from circumstances which

supplied wide planks – in this day and age we can very effectively

substitute high-quality plywood for the wide pine planks - without

having to compromise the designs or force the plywood to do something

it can’t.

|

“Here is a glued-lapstrake boat which

uses only five, wide planks. Note the sharply raked bow

stem which is the natural termination of such planking”.

Ross' Periwinkle |

Back to the country workshop. If the Magpie had been watching

a Dory or Oselver-derived design being loaded onto a trailer,

he would have seen that it took one human, not two, and that the

boat kept herself upright as soon as the bottom hit the trailer

rollers. Not only that, but an intelligent bird would also have

seen that the shape of the boat was perfectly suited to modern

timber construction, and that the design did not look pretentious.

There are many areas where common-sense has been overlooked in

design. One very common example is the design of centreboards

or daggerboards. The theorists will tell you that the best design

has a high aspect-ratio board, made with a high-tech foil section,

and set so the leading edge is vertical.

Now that is fine if you are sailing in a competitive class such

as the Eighteen Foot Skiff where the rules allow such things –

not to go for the last fraction of a second means being a looser.

But for cruising there is no need for such impractical things.

I recently had a wonderful days sailing on a stretch of water

which was somewhat infested with weed. The boat which was accompanying

me had a vertical daggerboard, and she just kept stopping, and

then drifting off sideways as relatively small amounts of weed

caught around the leading edge of the board and destroyed the

hydrodynamics. All that was required was for the board to be lifted

and the weed was cleared – but it had to be done dozens

of times.

In contrast, the boat I was sailing had a pivoting centreboard

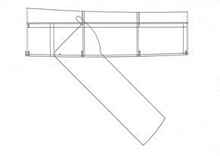

which was swept back at 45 degrees. Not once did I have to stop.

The boat just kept on sailing through the weed patches, and the

weeds slid back along the angled leading edge and swept clear

of the board. A similar situation occurs when encountering sand

bars and mud-banks. For cruising, just apply a bit of commonsense

to the design equations!

|

“Section of boat showing angled centreboard” |

There are many, many other examples of situations where common-sense

has been left to fall by the wayside in boat design. Consider

carefully before committing yourself to the task of building (or

buying) – think about the practical matters of operating

the boat, and trust you own judgement.

***********

|