| A few weeks ago, while sitting in

the nearly completed cockpit of my Stevenson Pocket Cruiser and

swiveling my newly cut tiller, I was struck by the sudden realization

that I can see the finish line. It’s still far away, but

it’s real and for the first time I know I will make it.

With the hull and cabin completed I am now building the rudder,

hatch, and other details that make the boat look even more like

a boat. A great deal of work remains, of course, but the list

is not impossibly long. As my “to do” list shrinks,

my confidence grows.

“What do you know,” I said out loud, genuinely amazed.

“I’m going sailing.”

It’s time to seriously research my long planned cruise.

As I mentioned last month, my interest in boat building was inspired

by fantasies of adventures in the South Seas. But I reigned in

this unrealistic dream and I settled for a small boat and a vague

idea of exploring protected waters closer to home. However, my

preoccupation with building kept me from investigating my options.

But as my boat takes shape, it’s time to plan my itinerary.

As a resident of southeastern Pennsylvania, the logical place

to start is the Chesapeake Bay, and that will almost certainly

be my “home port.” Truthfully, the Bay’s countless

inlets and islands could occupy me for years. But why stop there?

For inland sailors, the Chesapeake is only one part of an interconnected

network of canals, bays, lakes and rivers that encircle the eastern

half of North America. Collectively they form a 6,000 mile ribbon

of water known as the Great Loop. The idea of dropping my boat

in the water and ending up in, say, the Everglades or the Great

Lakes is almost irresistible.

But it’s also true that I probably won’t undertake

the whole trip—at least not for a while. So with a small

boat and limited time (let’s say a month or two), what portions

of the Loop are most worth exploring?

I began by investigating the most famous (and probably most traveled)

part of this inland passage—the Intracoastal Waterway. Following

a series of canals and bays, it provides a nautical Interstate

95 linking New York to Florida.

|

The Intracoastal Waterway |

I have happy associations with this southern migration. As a

boy, my family drove every winter from our home in Albany, New

York to a beachfront hotel in Florida. This was before the highways

were finished, so much of the trip was made on back roads. I vividly

recall the delicious sensation of leaving the winter landscape

of upstate New York and watching, with growing excitement, as

the scenery evolved from the familiar to the exotic. First the

snow thinned, then disappeared. Then the grass turned green and

the air turned warm. On two lane roads of Georgia and north Florida,

I searched for orange trees and Spanish moss. By the night of

the second day, I smelled sea air through the open windows of

our station wagon. We had arrived.

Now I dream of recapturing this drama of incremental change along

the ICW. I imagine beginning in the northern edges of the Chesapeake

during the last warm days of autumn and entering the Intracoastal

somewhere near Norfolk, Virginia. From the safety of a well marked

canal I sail and motor (as necessary), but at a leisurely pace.

I stop for the night at inlets, dock at interesting towns for

provisions, and chat with fellow sailors along the way. As the

weeks pass, I spy palmetto, palms, and mangroves. Just as the

mid-Atlantic has its first hard frost, I am sunning myself somewhere

near Key West. I’m six years old again, looking for shells

on a warm beach without a care in the world.

That’s the fantasy. But what is the reality? With no direct

experience, I rely on books and blogs. Opinions vary, but it’s

clear that the “Ditch” inspires both affection and

loathing among those who know it best.

To my first question—can the ICW be safely traveled in

a small boat? —the answer seems to be a qualified “yes.”

Boats much smaller than mine have made the journey. One of the

boat designers I admire most, Matt Layden, built a series of “mircocruisers”

no larger than my Pocket Cruiser. Several have completed cruises

down the ICW. One, the 14-foot “Little Cruiser” completed

the trip eight times—10,000 miles in all, according to a

Web site

devoted to his designs.

Many others complete the journey in everything from canoes and

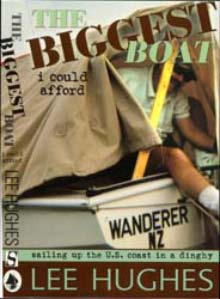

kayaks to daysailers. In The

Biggest Boat I Could Afford, New Zealand author

Lee Hughes chronicles his journey from Florida to Maryland in

a dinghy “not much bigger than a king size bed,” according

to the book’s jacket.

|

The Biggest Boat I Could Afford |

Conforming to the genre, his book emphasizes various dangers,

mishaps and amusing encounters along the way. The author, a novice

sailor with a fear of the sea, was “beached, swamped, [and]

wrecked” as he blundered north, but arrived safe and sound.

But I am also learning that the Intracoastal can be tedious,

dull and even annoying. Those who have completed the route point

out that the narrow canal limits opportunities for sailing. Teresa

Carey, who is currently completing her first trip down the ICW

in her 27-foot sailboat, recently wrote on her blog that the Intracoastal

is “a great place to start, establish your routines, learn

from others, and join a network of fellow wandering sailors that

will serve as a dynamic community and safety net.” But she

adds that it “is not my kind of ‘sailing’ where

the canals are so narrow that the only way to make progress is

to motor.” (https://sailingsimplicity.com/)

There are other obstacles, as well. Commercial traffic can be

a hazard. In what is probably the first account of a sailing journey

down the ICW, Henry Plummer recounts in The

Boy, Me, and the Cat several close calls with

barges during his 1912 journey from New England to Miami. More

recently, Ron Stob, author of the self published book Honey,

Let’s Get a Boat, described feeling both

small and vulnerable while treading his 40 foot cruiser around

the barges and container ships in Norfolk. Sailors also report

encounters with floating logs and other debris large enough to

easily puncture my quarter inch hull. Everyone complains

about discourteous powerboaters.

On the other hand, I don’t need to worry about two much-discussed

hazards—bridges and shallow water. For cabin cruisers and

large sailboats, bridges are probably the most persistent source

of delay and irritation. “Most cruisers begin their inland

treks at Mile Zero, at Portsmouth, Virginia,” writes Jon

Eisberg in a 2004 issue of Cruising World. “Unfortunately,

the curse of the first 20 miles of the Ditch is the nine bridges,

each with its own opening schedule. Unless one is under way from

Mile Zero well before first light, the better part of a day will

be required to cover this distance.”

“The first 50 miles, to Coinjock, North Carolina, can seem

like a forced march,” he continues. “The push to make

the next bridge opening is constant and ever at odds with the

necessity to reduce speed to allow the never-ending flow of powerboats

to perform a courteous pass. And by the first day’s end,

you may begin to think that courtesy is all but gone from the

world.” (https://www.cruisingworld.com)

My knowledge of these obstacles is sketchy. However, I assume

that with an unstepped mast my small boat can slide underneath

most of these low-slung bridges. If so, I anticipate mild feelings

of moral superiority.

In addition, my little flat bottomed Pocket Cruiser can skim

over the shallow and insufficiently dredged channels.

|

Paul in his pocket cruiser. |

In 1912, Henry Plummer was grounded countless times in his 24-foot

sailboat. Sometimes he would work all morning to free himself

from the muck, only to hit bottom again moments later. “Continually

we ran aground,” his son recalled. “With only three

or four inches of tide, getting off meant an endless shifting

of ballast and heeling of the boat over to raise her keel. After

doing this four or five times a day, it became more than just

monotonous.”

It’s better today—but not by much. Wikipedia reports

that “federal law provides for the waterway to be maintained

at a minimum depth of 12 ft (4 m) for most of its length, but

inadequate funding has prevented that.” In some sections,

it is maintained at seven to nine foot depths—a veritable

Marianas Trench for my boat, but a problem for many larger craft.

But I still worry about feeling like the odd man out in my homemade

boat. Based on the many blogs I have investigated, the ICW’s

cruising culture appears to be dominated by retirees with enormous

cabin cruisers powering south for the winter. They sound like

a fun crowd. Cruisers look out for each other and many friendships

are formed. I get the impression that, for some, the ICW is one

long cocktail party. But I worry about feeling overwhelmed by

floating Winnebagos. Is it still possible to enjoy quiet, solitude,

and leisurely exploration of undeveloped shores?

Perhaps. While much of the route passes busy marinas and sprawling

oceanfront developments, some portions remain relatively wild

and the passage through the Great Dismal Swamp in southern Virginia

looks downright primeval. Experienced cruisers also write about

detours that allow for real sailing and exploration of quaint

towns. Those destinations, alone, would make the trip worthwhile.

|

Scenes sailing voyages entail. |

Still, I’m not ready to pack my bags. There are several

other options worth investigating. If the Intracoastal is less

than perfect, what about taking a trip north to Canada—or

heading like a latter day Huckleberry Finn down the Mississippi?

That’s the topic of my next column.

*********** |