Part 1 - Fore Deck Structure

Part 2 - Side Deck Structure and Fitting the Ply Decking

The scope and direction of this piece was never intended. Since realizing a few seasons ago structural work and deck replacement would be required on PLUM CRAZY and at that point having found canvas decking an option in the rules, it had been my intention to do a traditional canvas/white lead decking job and to document the project in an article; however, when I first mentioned the idea to Chuck, he asked if there might be alternative methods to using lead. Yes, there are but in my experience none, to date, had proven nearly as effective. After some reflection I thought perhaps it was time to revisit the subject.

Why canvas?

There are several reasons for the choice, first canvas decking provides a natural nonskid surface, secondly it is easy to work and doesn’t cause skin irritation, thirdly it is a VERY traditional deck covering that works: some years ago when my old #103 Wianno Senior needed new frames, keel, and centerboard work I started getting into things by removing the cuddy and enough deck (straight laid pine) to get at the frames. ZEPHYRINE was canvassed, traditionally with white lead, and it was tenacious. I was impressed.

Why alternative beddings?

Lead paint poisoning of children. We are all familiar with the history and the problem from paint flakes. Lead as a drying additive in paints is outlawed and, in some states, it is illegal to even bring lead paste across the state line. So, since the 1970’s, alternatives have been sought.

Wet paint…

Having talked over this method with several old-timer friends, I believe, given the time frame the method was introduced, it originated as a simpler way to introduce lead into the bedding process—since paints, at that time, contained lead.

Let’s talk for a minute about lead. Lead was principally a drying agent added to paints, or so it was stated. However, lead is also a biocide and fungicide and thus a preservative, providing mold or mildew protection (which spell DEATH to canvas). Decking aside, white lead paste was also a traditional bedding compound used in plank scarfs and between dead wood and keel sections, thus it was a well-known preservative in marine applications.

Since the removal of lead from paints, paint bedding is less discussed in print now than it was in the 1980’s; however, my first venture into the method occurred early in my professional boat carpentry career when I was asked to rebuild (fully restore) an Old Town cedar/canvas dinghy. This entailed clamping the ribs, keel, stem & transom pieces into a shape resembling an aged photograph provided by the owner, having the owner approve the shape, lifting lines & building a new boat using just enough old parts that it could be construed as restoration. In this instance, following some published canoe building suggestions, I bedded the canvas in wet marine paint, stretched and tacked it down and then painted the outside with coat upon coat of filler (paint and colloidal silica) until smooth. The boat came out wonderfully, still I felt uneasy about the life expectancy of the canvas given the use of lead-free products.

|

Restored Old Town cedar/canvas dink |

Lagging adhesive:

Canvas pipe lagging has been around for many, many years and mention of lagging adhesives, including an editor’s note concerning Arabol, first appeared in WoodenBoat Magazine in 1976 (Cochran,Leaks are Lousy, Volume 13, p60) from thence it passed into legend and the lore of boats.

Wooden boaters, it seems had to have Arabol-- see WoodenBoat Forum thread (keyword Arabol), despite reported failures as early as1979 by no less a boating icon than Donald Street (Street, Leaky Decks—Watertight Solutions, WoodenBoat #25, p89).

Having dealt, as Mr. Street had, with a failed adhesive laid deck covering, I wonder at the veracity of lagging adhesive for successful exterior marine applications. On the East Coast, two often specified (in building specifications) canvas-lagging adhesives are Childers CP-50A and Foster 81-42W, neither of which is recommended for exterior use (the specifications I turned up listing Arabol employed it in same applications as those specified for Childers and Fosters).

In all my research I have found only one canvas-lagging adhesive listed as interior/exterior by the manufacturer, that is Lag-It by Ductmate Industries, and despite the exterior identification it is only rated water-resistant, not water-proof. Further, none of these products provide mold or mildew protection (which, again, spell DEATH to canvas). So, as mentioned, I question their veracity.

Dynel/epoxy:

Another alternative to lead bedded canvas was/is Dynel cloth bedded in epoxy. This method reportedly imitates canvas in appearance/nonskid characteristics while providing the durability of fiberglass. I have used the method once, on the deckhouse of a 40’ sailboat after the failure of a relatively new professionally done (by a well reputed boatyard) adhesively bedded canvas top. The initial job had been expensive with two deck lights, companionway, forward hatch, and all moldings having been replaced at the same time. The adhesive failure in relatively short time (about 4 years from re-comissioning) now required all this to be removed yet again and the owner was done with canvas.

Prep for Dynel covering—a MUCH younger me |

|

The Dynel job obtained good results, yet it is much closer to glass sheathing than canvassing and while it does provide a fabric appearance it is not the same as canvas.

What is the answer?

My thoughts turned to Pete Culler. I had vague recollections of him having mentioned preserving his canvas sails in Cuprinol. So I went looking. Sure enough, in Skiffs And Schooners, (Burke, Pete Culler On Wooden Boats, page 112, International Marine) I found it. This got me thinking; why not use Cuprinol as the fungicide in my bedding. I ran the idea passed my buddy Nim Marsh, who has been around wooden boats and the industry much of his seventy years. His reaction was favorable considering it fell outside the comfortable traditional norm, so I figured I was on to something.

Cuprinol (No. 10) wood preservative is a mineral sprit and kerosene (paraffin oil) based product employing copper napthenate as the active ingredient. Anyone familiar with Culler’s writings knows his views on the use of kerosene as an excellent wood preservative. So here it was, replete with copper napthenate biocide/fungicide, what could be better?

Reasoning told me the concept would work but still I was hesitant to commit my canvas and all the new moldings on a hunch. I decided more research was required.

Bill Clements is a (now retired) local builder of cedar/canvas canoes. I had talked with him about the project a couple years ago concerning the appropriate ratio of lead paste to linseed oil when mixing the bedding and wanted to get his thoughts on the matter. Bill still maintains his web site and still lists some supplies there, although his contact link appears no longer to function; however, the link wasn’t necessary. The following is quoted from Bill’s site relative to his canvas filler, “About 15 years ago I developed an unleaded filler that I have been selling along with the leaded version. The unleaded filler uses copper napthenate as the fungicide. I believe that this filler is every bit as effective as the old leaded version”.

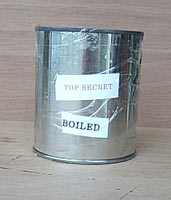

Proof at last! Thus, one rainy Saturday morning I set out to devise my concoction. My initial ingredients were Boat Yard Bedding Compound (1), boiled linseed oil, Cuprinol, and later Kirby’s white oil based marine primer (a nice thick paint). I won’t bore you with all the tests and trials on mixing ratios. My final compound consisted of the following (by volume): approximately 30 ounces bedding compound (what was left in a quart can following my test mixes), 6 ounces boiled linseed oil, 6 ounces of Cuprinol and 3 ounces of primer paint. The thinning agent for the bedding compound is linseed oil—it will not mix with the mineral sprit based Cuprinol alone. It will however mix with linseed oil thinned with Cuprinol. Scoop the bedding compound into a 1-gallon plastic container. Combine the oil & Cuprinol together in a separate container and then slowly add to the bedding compound and stir thoroughly until well mixed. Add the paint and stir again (my tests pieces showed that the addition of the paint to the mix aided spread ability, quickened drying, and tempered the color to a pastel green). The final mix should spread easily with a brush yet retain sufficient stiffness to keep it on vertical edges without running.

|

|

Ingredients and bucket—after the fact

(1) Perhaps Dolphinite would be a better choice; I noted the Interlux product contained a large amount of hard particles/unmixed fill, which necessitated picking bits out when brushing. I have never experienced this with Dolphinite. |

Deck Preparation: Make up templates for all combings and moldings prior to laying the canvas. Place and cut all through deck item holes (oar locks, mast partners etc), putty over all fastener heads, rout all edges with round-over bit and sand surface with 200-grit sandpaper. Tack down surfaces and apply two coats, wet-on-wet , of straight Cuprinol (wear respirator, eye protection, rubber gloves and long sleeved clothing). Let boat dry for 1 week.

Bedding the Canvas: Mix the bedding per above, brush on—covering deck, stringer/beam facings, and outside edge of hull with a thick even coating. With the aid of an assistant (recommended) open the canvas (I used a single piece owning to the small size of the boat) stretch it taught, lay it onto the bedding and work it down with a roller to remove bubbles and unevenness.

D.N. Goodchild’s booklet How To Lay And Repair Canvas Decks (Press at Toad Hall, Anon, 2001) advises giving the canvas a coat of boiled linseed oil by section as soon as it is tacked down, to prevent the canvas from soaking up all the oil from the bedding. I found that when working short handed, it was helpful to brush on the oil before making final adjustments during stretching and tacking as it helped prevent the canvas from lifting and dragging the bedding.

I used two types of “boiled” linseed oil. For mixing the bedding I used paint store oil, which is not boiled but is raw oil containing chemical driers. For coating the canvas; however, I wanted an authentic oil and contacted Bill Rickman of American Rope and Tar, who is always on a quest for such materials. Bill supplied me with some wonderful boiled oil. This dark amber oil, resembling Grand Marnier in color and clarity, offers excellent body and brush characteristics-- spreading evenly and giving consistent absorption; it will certainly find a place in my shop from now on for any sealing and oil finish work.

|

Handy tools—the pliers ease the burden on hands

Handy tools—the pliers ease the burden on hands

Uncle Billy’s boiled oil |

The mechanics of fitting are straightforward and well documented in some 14 WoodenBoat entries (see index at end), including their June 2009 edition, and the other publications referenced herein, so I won’t dwell on them. I like copper tacks, some folks use Monel staples, some folks sew seams and others just tack them down. Some use covering battens on seams while some inlet the deck. I have used all these methods at one time or another, each has merits and drawbacks; the choice is solely a personal matter depending on the boat in question.

|

|

Canvas bedded, wet out with boiled linseed oil, tacked down and rolled |

Painting:

Don’t forget to cut the canvas out of the through deck openings before painting…

The Goodchild booklet advises a well-thinned initial primer coat of flat paint followed by two additional primer coats slightly thinned. Finish coat is specified only as “a coat of deck paint right from the can”. Chapelle (Chapelle, Boatbuilding, 1969 Norton p262) takes the advice one step further stating, “It is well not to try to get a glossy deck…” This advice, in part, has to do with the application—in order to achieve a glossy (smooth) finish; all the grain must be filled. This negates the wanted nonskid properties of having the fabric grain somewhat bold. Also, according to both Chapelle and the Goodchild booklet, the amount of paint needed will cause the surface to crack or “alligator”.

For PLUM CRAZY, in keeping with the copper napthenate fungicide concept, the initial primer coat was cut with Cuprinol to the consistency of milk with a dash of Japan Drier added to compensate the kero. Mineral spirits were stirred in occasionally in order to maintain consistency in the bucket—initial primer coat is illustrated below.

|

First primer coat well dried, masked off & fitting mahogany combings |

The remainder of paint job, done subsequent to dry fitting and removing the combings, followed as prescribed above: two additional primer coats and topcoat of Kirby’s “cream” colored deck paint, lightly thinned with Kirby’s conditioner.

Final deck assembly |

|

Conclusion:

In researching this topic I found references to laying canvas on dry decks, using paint bedding, lead bedding, lagging adhesive, waterproof cement, flexible adhesive and even wood glues. For the boater interested in canvas decking I can only recommend that the period of your references be considered: dry lay (but paint saturated), paint laid and lead paste laid deck methods all were devised when paints contained a very effective biocide/fungicide: lead.

More modern suggestions lean towards adhesives—here I can only caution, just because the adhesive is “waterproof” does not imply it will act as preservative. If canvas becomes infected with mold/mildew it will not remain attached to an adhesive but will rot unseen beneath a healthy looking layer of paint—do your research and use only materials containing fungicide.

Commercially available industrial coatings with significant mold and fungus protection are available (see Foster 40-20 Fungicidal Protective Coating Test Results White Paper, www.fosterproducts.com), and while not “adhesives” would probably work as a substitute for lead paint or lead paste bedding. Such coatings are not inexpensive, about $150.00 a gallon, and are not normally available in small quantities (figure 4-gallon case or 5-gallon bucket minimums). 40-20, unlike bottom paint, does not have to be burnished to stay effective so it is a promising consideration, especially on a larger application and one quite frankly I thought to try here if I could have gotten around a 4-gallon minimum.

Still, I believe Pete Culler and Bill Clements knew their stuff and I have no reservations in employing or recommending their suggestion relative to Cuprinol/copper napthenate—the proof, as they say, is in the pudding and both of these gentlemen have proved their puddings.

I’ll close with a few words from Bud McIntosh (How to Build a Wooden Boat, McIntosh, 1987, WoodenBoat Publications, pages 157-158), as I could say it no better:

Outside the window as I write this sits the sloop MICKY FINN, built in the year 1937, and a damned plain job at that…For a deck, we nailed tongue-and-groove pine sheathing to deckbeams and sheerstrakes, smoothed and trimmed it somewhat, primed it with one coat of lead ‘n’ oil, and stretched and tacked number 10 canvas over the whole business…There she sits, outside the window, sound aloft and alow, waiting for spring and another season afloat, with most of the original canvas still in tact…Canvas I have loved, and it has functioned predictably for me for slightly over half a century.

***** |