Mention the words “Grumman Canoe” and most people

familiar with small craft will envision the 17’, heavy

duty, aluminum canoe that they paddled about in at scout camp

or the boat they rented from a canoe livery to paddle down a

river for the day. Using WWII era aircraft technology, they

were well built, relatively stable, zero to low maintenance

and well suited for the post war population who wanted to get

into boating with a minimum of fuss and expense. William Hoffman,

a vice president at Grumman Aircraft Corp. and canoe enthusiast,

is credited with coming up with the original design concept,

and the first boats went on the market in the mid-1940s. They

ranged in length from 13’ to 19’ and many of these

boats are still going strong fifty or sixty years later. The

hulls were constructed of thin aluminum sheets that were stretched

to shape over male molds and then assembled with hundreds of

rivets that attached the two halves of the hull to an extruded

aluminum keel. Aluminum seats, ribs, thwarts and bow and stern

flotation tanks finished off the construction. The “standard”

models were not all that light, and with all the rivets did

cause a fair amount of drag when being paddled. That said, the

hulls bordered on indestructible and were the canoe of choice

for camps and rental liveries. I paddled many Grumman canoes

as a youth, and later owned a 13’ lightweight model. They

could be stored outside and uncovered all year and any dings,

leaks or popped rivets could be easily repaired with hand tools.

I live close to the Marathon, NY plant where Grumman boats were

manufactured for several decades, and during a factory tour,

I was surprised at how lo-tech the construction was. Rivet holes

were hand drilled with electric power drills, and once the hull

sections were fabricated, trimmed and drilled, assembly was

simply a matter of aligning the component parts with rubber

gaskets and riveting them all together. Boats came off the assembly

line in a continuous stream and from nearby Interstate 81, drivers

could see scores of hulls stockpiled in the storage lot adjacent

to the plant awaiting transport to dealers around the world.

All in all, this was a very successful design, and thousands

of the hulls were manufactured for 60+ years. Over 300,000 boats

were built in the three decades leading up to the mid-1970s

and production peaked in 1974 with production of 33,000 hulls.)

(Striegel, 2007)

|

From nearby Interstate

81, drivers could see scores of hulls stockpiled in the

storage lot adjacent to the plant awaiting transport to

dealers around the world. |

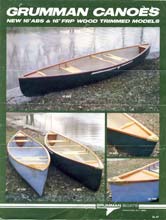

In the early 1960s, Grumman bought a controlling interest in

Pearson Yachts Company in Bristol, RI and in a bid to expand

into the lucrative fiberglass boat market, and somewhere in

the late 1970’s, they came out with a 16’ Grumman

brand canoe in both fiberglass and Royalex. I happened to see

one of the fiberglass hulls at a dealer’s shop, and it

was love at first sight. The 16 foot hull was truly a thing

of beauty. It was light, stiff with a fine entry at the bow

and long flat run aft and no keel. The quality of the fiberglass

work was extraordinary, and it was finished off with mahogany

gunnels, ash carry yoke amidships and caned ash seats. About

the only thing I didn’t like about the boat were the gunnels

that looked unnecessarily heavy and overbuilt, but it was the

nicest fiberglass canoe I had seen to date. I had to have one,

but the price tag at over $1,000 was prohibitive at the time,

so my boat-lust dream of owning one went into hiatus.

| It was the nicest fiberglass canoe I had

seen to date. I had to have one, but the price tag at over

$1,000 was prohibitive at the time, so my boat-lust dream

of owning one went into hiatus. |

|

Time marched on, and the Coleman Company came out with their

very successful line of Royalex type canoes that sold for $300

or less at K-marts across the country. With their aluminum tube

frame and plastic seats, these boats were not going to win any

beauty contests, but they were rugged, functional and certainly

affordable. I still lusted after the Grumman fiberglass model

but found that they were no longer commercially available, and

I have to believe that they got priced out of the market by

the far less expensive Coleman canoes and clones from other

companies. It began to look like a Grumman fiberglass canoe

was not to be in my future.

Again, time marched on, and in the fall of 1980, I found myself

at the Sail Locker, a little hole-in-the wall sailboat shop

in Binghamton, NY. The Sail Locker was owned by Chuck Durgin

whose real passion was sailing canoes, and in the back of his

store there was a stack of bare, unfinished fiberglass canoe

hulls nested together. Closer inspection showed that they were

Grumman hulls (be still my heart!) and based on the Hull Identification

Numbers, they were built in 1979. I inquired, and Chuck told

me that Grumman had discontinued the manufacture and sale of

their fiberglass canoes, and he was able to buy up a batch of

the bare hulls and components (ash carry yoke/thwart and ready

to install caned seats). He had plans to convert one or more

of them to “C” class sailing canoes but, yes, he

would sell me one! I came back the following week, and for $200

picked up a light blue bare hull, thwart and seats.

The hull was fresh out of the mold. When the hull was laid

up at the Pearson plant, the fiberglass mat and resin overlapped

the top of the mold and formed a right angle flange that I would

eventually have to trim off, but this flange helped to maintain

the shape of the hull until wood gunnels could be attached.

The sidewalls of the hull were thin, but the bottom of the hull

appeared to have a half inch or so of foam or balsa wood for

stiffness and flotation, and the hull was light, stiff and beautiful

to look at. To finish the boat off, I would need to fabricate

and install gunnels, flotation tanks at the bow and stern, and

install the seats and thwart.

|

The sidewalls of the hull

were thin, but the bottom of the hull appeared to have

a half inch or so of foam or balsa wood for stiffness

and flotation, and the hull was light, stiff and beautiful

to look at. |

White ash (Fraxinus americana) would be the best wood

for the gunnels. Well seasoned ash is an excellent material

for gunnels and would match the ash seats and thwart, but none

of the lumber yards in the area carried ash in the 17’

length that I needed, and I did not want to scarf shorter pieces

together. Finally I located a man in the area who restored old

canoes as a hobby and he said he has some ash boards that he

would be willing to part with. I visited his shop near Cato,

NY and ended up buying one 18’ white ash plank. It was

just what I wanted but it had just been cut and rough sawed

a few weeks before I bought it, and it was as green as the beer

on St. Patrick’s Day. Undaunted, I carted it home. At

the time, I had access to a nice wood hobby shop at the college

where I work, and I planned the plank down to ¾”

thickness and then ripped the planned plank into 7/8”

pieces. I got eight pieces out of the plank and figured that

planned and ripped, they would season faster with air exposure

to all four sides of each piece. I was amazed at how flexible

these 18’ long pieces were, and I stowed them in the rafters

of my garage and waited for the better part of a year before

I could move to the next phase. The cost of the plank was $20,

so I was still in bargain budget mode.

When the wood was sufficiently air cured, I inspected each

piece carefully. I had to reject a few of the eight pieces owing

to twists, warps and other imperfections, and at least two of

the rejects ended up as high priced tomato stakes in the following

summer’s garden. The others were flawless with no knots,

burrs or punky areas and ready to go.

The original Grumman gunnel design was almost flat and looked

a bit like a racer with a minimum of freeboard. I liked this

look, but decided to modify it slightly by curving the gunnels

up slightly at the bow and stern. As there was plenty of spare

freeboard that came with in the bare hull, I also added an estimated

inch of freeboard compared to the original specifications. To

position the outer gunnels, I simply laid one against the bare

hull the then “C” clamped in at intervals and made

adjustments by eye until I arrived at the desired shape. When

I was happy with the shape, I scribed a line the gelcoat of

the hull and removed the clamped gunnel section. The next step

was to mask up the area below the scribed line with 2 inch masking

tape (to catch the epoxy resin run-out.) I then carefully sanded

the blue gelcoat off the inch or so above the line to get a

better resin bond and then glued the oversized ash gunnel section

to the topsides with WEST epoxy resin thickened with chopped

cotton thickener to about runny peanut butter consistency. “C”

clamps at about 16” intervals held the gunnel outwall

in place. To insure a good bond, I then drilled small holes

at about 6” intervals from the inside of the hull and

into the gunnel section and inserted ¾” long temporary

pan head screws. With the clamps and temporary screws, I got

a nice even resin run-out top and bottom, and I carefully wiped

up the resin on the bottom to make sure it didn’t end

up staining the gelcoated topsides. When the resin was partially

cured, I removed the masking tape and cleaned the area with

a rag dipped in acetone to remove any remaining resin or tape

residue.

| To position the outer gunnels, I simply

laid one against the bare hull the then “C”

clamped in at intervals and made adjustments by eye until

I arrived at the desired shape. |

|

When the cure was complete, I transposed the dimensions at

12” intervals along the other topside, laid the next gunnel

section on these hash marks, scribed a line and installed the

second outer gunnel the same fashion described above. When both

outer gunnels were installed and the resin was completely cured,

I then rough sawed off the scrap fiberglass and flange off the

topsides about ¼” above he top of the gunnels and

removed all of the temporary pan head screws.

Installation of the inner gunnel section was easier, but the

sections had to be pre-cut carefully and beveled at the ends

so they formed a mitered joint at the bow and stern where the

starboard and port inner gunnels met. Once the sections were

cut to final shape, I dry fitted them on the inside of the hull

and drilled holes at 12” intervals from the outer gunnel,

through the fiberglass shell and slightly into the inner gunnel

sections. I then countersunk the holes and again dry screwed

the inner sections in place with flat head brass wood screws.

When everything fit properly, I masked up the inside of the

hull, attached the gunnel sections with thickened epoxy and

screwed the assembly together using the wood screws as clamps.

Using a plug cutter, I then made plugs from a piece of scrap

ash, and drove the plugs into the countersunk holes with a little

unthickened epoxy. The last step was to clean off the excess

resin run out on the bottom with acetone solvent.

When all the epoxy had cured, I belt sanded the top of the

gunnels with a 100 grit belt so the fiberglass edge was sandwiched

between the outer and inner gunnels and then rounded over the

edges of the gunnels with a router and 1/4” diameter round

over bit. I left the inner gunnel square on the bottom, but

with a sharp block plane, I beveled the underside of the outer

gunnel so it was full sized where it joined the fiberglass hull

but a little thinner on the outer edge. This bevel reduced the

weight a little and was esthetically pleasing. Hand sanding

down to 220 grit sandpaper finished off the gunnels. With the

finished gunnels in place, I was amazed at how stiff the topside

of the hull became.

Installing the thwart and seats came next. I cut the thwart

to size and bolted it onto the underside of the inner gunnel

exactly amidships. I used two flat head 3/16” stainless

steel flat head bolts without epoxy. Canoe thwarts are easily

broken (mostly through clumsy moves in the cockpit!) and I figured

if I ever had to replace it, not having it glued in place would

make the retrofit easier. Also not gluing the thwart to the

gunnels allowed for a little flex without the risk of cracking

the gunnels or the thwart.

|

Installing the thwart

and seats came next. I cut the thwart to size and bolted

it onto the underside of the inner gunnel exactly amidships.

I used two flat head 3/16” stainless steel flat

head bolts without epoxy. |

The caned seat assemblies that came with the purchase were

wider then the inside of the hull, and before fitting them,

I had to determine where I wanted them positioned fore and aft.

I scaled the locations from an advertising brochure photo and

a friend’s 16’ canoe. I then sawed the seat frames

to the proper width and installed them using 3/16” flat

head stainless steel bolts with 3/16” inside diameter

copper tubing as spacers. Again, I looked at the advertising

brochure photo to get an idea how deep each seat needed to be

set into the hull knowing that I could always use longer or

shorter bolts if it turned out that the seats needed to be higher

or lower. As luck would have it, the location of the seats seemed

good right from the start and no adjustments were necessary.

Now the only remaining fabrication that remained was making

the flotation tanks in the bow and stern. Again, looking at

the advertising brochure photo, I scaled the approximate size

of the tanks and made them out of metric (about 3/16”

thick) marine mahogany plywood. To get the right shape for the

vertical and horizontal panels I made cardboard templates and

kept trimming then until I got the right shapes. I epoxied the

horizontal panel to the underside of the “v” in

the gunnels and then covered the top of the panel with 3 oz.

fiberglass cloth and WEST epoxy resin. This added strength and

helped to insure a water tight fit. I then fabricated a ¾”

by ¾” piece of mahogany with rabbets and limber

holes to join the horizontal panel to the vertical panel. I

attached the vertical panel to the sides of the hull with epoxy

resin and 2” fiberglass tape, and then covered the panel

with epoxy resin and fiberglass cloth. As a final step, I installed

a drain plug in the bottom of each tank and a 5” inspection

port on the vertical panels and then placed a plastic bag inside

each tank filled with Styrofoam packaging “peanuts”

just to make sure the flotation tanks would function even if

damaged or holed.

I finished the bare wood with Interlux spar varnish and painted

the bare fiberglass interior and new vertical tank panels with

Pettit two-part, grey epoxy paint. The combination of the light

blue hull exterior and grey interior went well with the blond

ash wood and mahogany components.

The boat finished out at about 65 lbs., not ultralight by canoe

standards but lighter than most 16 footers and yet heavy enough

not to be blown all around in a brisk cross wind. True to my

predictions, the boat had good manners and paddled easily in

the flat water conditions it was designed for. It also adapted

well to the subsequent addition of an outboard motor mount and

my little 1.2 h.p. outboard motor. I still think about adding

a “C” class sailing rig with leeboards and a Laser

style sail but maybe that will be another story for another

time.