| Part 1: Genesis

|

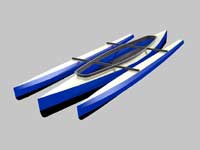

The XCR,

designed by Chris Ostlind |

I showed up at Chris’ shop hefting a pair of

huge Granato’s mozzarella and tomato sandwiches,

the staple for our boat-centric lunch meetings, but

I couldn’t let myself sit and eat. I was too

excited to get another look at the hull of what I

had just learned would be my next boat. To my relief,

it was just as I remembered it; surprisingly huge

compared to my Mill Creek.

When my boys were small I could actually fit my entire

family of four into the 8-foot cockpit of my 16 ½

foot Mill Creek kayak-cum-trimaran with reasonable

comfort. But those days are long gone and The Guys

are now 12 and 14 years old. The XCR, even though

it’s only two feet longer than the Mill Creek,

is built around a high-capacity expedition canoe hull

that will be spacious by comparison, especially when

anchoring out and sleeping, either by myself or with

one of my boys along stretched end-to-end. On family

outings the kids can lounge out on the trampolines.

Boy, did they perk up when I mentioned trampolines.

They had visions of themselves bouncing along and

performing all kinds of aerial acrobatics as we sailed

off to the horizon.

I’ve been thinking more about trailering since

my spine started trying to tell me that it’s

time to lower my expectations for cartopping. I swear

the boat hanging from my garage ceiling gains 20 pounds

every year. If I’m going to use a trailer anyway,

I might as well go for a bigger boat. Not BIG, mind

you, just bigger. Now that I’ve built half a

dozen or so small boats I’ve learned a lot about

what I like and don’t like, so the time seemed

ripe to start thinking about a new boat with a lot

of the things from the “I like” list.

For starters, I’m an unabashed trimaran geek,

so there was no question about how many hulls it would

have.

Because of storage concerns, my next boat and its

trailer would have to fit through a 55-inch wide gate

and store in a 20-footish long space. Even though

it will live on a trailer, I still wanted it to be

light, so I can move it around my yard and launch

it either with a vehicle or by hand. I wanted it to

be bullet-proof-sturdy, I wanted it to be fast, and

I wanted it to be a Chris Ostlind trimaran.

|

Click thumbnails

for larger views |

About Chris

I always have at least one of Chris Ostlind’s

designs taped up on the wall in my shop. I really

want to build one myself, but I just don’t have

the time to dive into a big project right now. I told

Chris what I was looking for and asked him if there

might be a chance I could get him to build me a boat,

or at least some of the major components, and before

you know it I’m handing over the down payment

for the XCR that’s already gestating in his

shop.

|

Chris lays up

the cockpit coaming on a form that he carved

from rigid foam |

Chris, besides being a good friend, is an all-around

impressive guy and a modern renaissance man of sorts.

He’s also one of the most prolific, versatile

and observant boat designers around. What a treat

to have the designer actually build this boat for

me, especially when he’s a craftsman of Chris’

caliber. A nod of gratitude to whatever weird chain

of events brought Chris to the high deserts of Utah,

an unlikely home for a gifted boat designer, indeed.

The XCR

The XCR is an ideal expedition boat. With a main

hull inspired by Verlen Kruger’s Cruiser canoe,

it’s a sturdy craft that’s designed to

stand up to journeys of thousands of miles. It has

a deep, voluminous cockpit with a high carbon composite

coaming and tubular thwarts, also of carbon fiber,

that double as sleeves for the outrigger beams (akas,

for those who prefer the Polynesian names for things).

And nothing gives me more peace-of-mind in cold water

than a pair of large, buoyant outrigger hulls (amas).

The construction is sturdy and lightweight. Impressively

so. The main hull, which only weights sixty-something

pounds, is made of 4mm Okoume marine ply, layered

with 6 oz. fiberglass cloth set in epoxy inside and

out. The joints are filleted and reinforced with additional

2” strips of bias-cut fiberglass. The side decks

are reinforced with rows of heavy-duty hanging knees,

which are set closer together at the thwarts to better

distribute the loads from the outriggers. Sturdy fore

and aft decks are reinforced with carbon fiber. It’s

a marvel of strength and weight economy. Here’s

what Chris has to say about it:

“The use of carbon fiber in this boat

is because of a personal decision to build a light,

but very strong craft for Kellan.. The carbon is

used in localized application zones where loadings

are potentially high and a high strength to weight

ratio specific to the material is beneficial. You

see it on this boat in the aka beams, thwart tubes

and coaming which are all subject to potential high

loadings from the sailing application of this design.

“Let's face it, carbon also has a very

high coolness factor. All three of these load path

areas on the boat could just as easily be addressed

with a glass, or wood and glass coaming, along with

aluminum akas and aluminum or glass thwart tubes.

The under deck areas around the thwart tubes are

re-enforced with an extra layer of 6 oz. glass and

additional red cedar knees to spread the loads of

the aka mounting points.”

To tell you the truth, I feel kind of lazy, being

the client and not doing any of the work myself, but

on the other hand it’s really a great ride,

kicking back and watching Chris work his magic at

things that would leave me scratching my head.

|

The oak bow

handle is a nice design flair |

This will be a fun boat for day sailing to be sure,

but it will also be a sturdy vehicle for serious minimalist

adventuring on the Great Salt Lake and some of my

other favorite haunts, like cruising the shores of

Jackson Lake in the shadows of the Tetons and gliding

though the majestic canyons of Lake Powell. But for

this boat I’m also thinking of adventures farther

from home. For starters, I have my eyes set on the

San Juan Islands and The Sea of Cortez.

|

The XCR main

hull nears completion. Chris built these handy

cradles to support the boat and move it easily

around on castors |

Why a Tri?

Every now and then a monohull vs. multihull thread

pops up on one of the Yahoo groups and often builds

to a near-religious fervor. You get the impression

that any day these folks, monomen and multigeeks alike,

are likely to haul their tiny plywood boats down the

seashore and head off for the Roaring Forties, and

that their survival depends entirely on how many hulls

they have in the water. Anyone in the opposing camp

is surely headed for certain disaster.

For me it mostly down to this:

First, if the water is 40 degrees, especially if

my kids are aboard, a ten-foot beam brings me a lot

of peace of mind about the possibility of anyone ending

up in the drink. Remember what I said about learning

what I like and don’t like about boats? Well,

I like small, lightweight boats but I DON’T

like capsizing. Yes, you can capsize a trimaran –you

see it in those dramatic racing videos - but a cruising

tri sailed conservatively on protected waters is very

hard to get upside down. And a trimaran, since it

still has a real boat hull in the middle, gives you

a place to hunker down out of the weather.

Second, a multihull can be built tough yet remain

extremely lightweight. No ballast needed. The XCR

is just the right size that it can be launched anywhere

you can get to water. I’ll use a ramp when I

can, but if there’s no proper ramp I’ll

wheel the trailer to the water by hand. And when even

that isn’t an option, I can carry the hulls

and rigs down to the shore and assemble them on the

beach.

Third, and I consider this a bonus, if it will do

12 to 15 knots I have a better chance of getting to

safety ahead of the storm.

The XCR also has some interesting hull configuration

options. The akas are built in sections that snap

together easily with the same kind of spring buttons

that are used for adjustable tent poles. For storage

and transportation you take the center section out

of each aka and reattach the amas close to the main

hull. Clean and simple.

|

The XCR in trailering/Storage

configuration |

Alternate Propulsion

On it’s own, the XCR’s main hull is

a superb expedition canoe, so it glides along very

well with a couple of single blade canoe paddles.

When I want to use the XCR as a motorboat, I’ll

simply leave it in the narrower trailering configuration

and clamp on the outboard for a very light but stable

craft that will skim along quite impressively on only

2 horses.

|

The XCR gets

its first paddling test in the icy water of

the Great Salt Lake marina |

Decisions

We had to decide on the sail plan pretty early in

the build because the mast locations would dictate

where Chris would place the thwarts/aka tubes, since

they would also double as mast partners. Chris was

very patient as I waffled, hemmed and hawed, and considered

just about everything from high-tech roller-reefers

to classic gunters rigs. In the end we settled on

a cat ketch plan with a pair of identical, fully-battened

high-aspect sails slotted into unstayed aluminum masts.

These can be used in tandem as a cat ketch rig, or

one sail can be stowed and the other moved to a central

mast step. In addition, both sails will have two sets

of reef points. This combination of sail configurations

will give me all kinds of options for dealing with

any kind of weather.

|

One rig stowed

as a simple way of reducing canvas |

You can also transfer one of these same rigs to several

some of Chris’ smaller designs, so when I get

around to building an ultralight solo boat one of

these days (I’m thinking of Chris’ Solo14),

I can use one of my XCR rigs for that as well.

Once the sail plan was locked down I ordered the

sails from Stuart Hopkins of Dabbler Sails. Chris

placed an order for the mast components and moved

onto his next task, which was to epoxy the thwart

tubes in place and reinforce them.

|

The thwarts

tubes are installed. These double as mounting

sleeves for the outriggers |

Once that was done we had a finished canoe on our

hands and Chris thought it would be a shame to not

take her out for a paddle, despite the fact that it

was the middle of January in the Rocky Mountains.

So, one cryogenic Saturday afternoon we headed out

to the Great Salt Lake marina - where the water was

still liquid - and plopped her into the lake without

much ceremony. Chris’ wife Lorrie was kind enough

come along and snap pictures. She did jumping jacks

to keep warm while we launched and climbed aboard.

The air temperature was 25 degrees F and the water

was a balmy 26. That’s colder than the water

at the poles, mind you, due to the high salt content.

It was a strange, hazy day and the water and sky blended

into a uniform horizonless void that gave us the sensation

of paddling off into some kind of ethereal Twilight

Zone. Not that that’s necessarily a bad thing.

It was a short trip; we hugged the shore for a while

and then headed out into the lake and took a turn

around the nearest buoy before turning back for the

marina. Chris gave me the willies for a moment when

he half-stood to switch from a kneeling to as sitting

position, but the XCR proved plenty stable. There’s

a lot of comfort in knowing that the quarter-inch

shell between you and a 26 degree plunge is solid

and reliable. I’m looking forward to a long

and intimate friendship with this boat.

|

Paddling the

XCR into the void |

In the next article we’ll see the XCR blossom

into a trimaran and get her wings.

XCR

Plans available from Duckworks

Other Articles by Kellan Hatch:

|