| On The Virtues

of the Fuselage-Frame Skin Boat

Full disclosure: The plans for Egret, a fuselage-style

skin-on-frame kayak of my own design, are available

from Duckworks.

One might therefore be inclined to think that this

article is entirely self-promotional, and that I’m

just singing the praises of the fuselage frame because

I design kayaks this way, but that is not accurate.

The article is only partly self-promotional, and I

really believe what I say about fuselage frames, otherwise

I wouldn’t design them this way.

The word “fuselage” is from the French

for “spindle-shaped” and is an aircraft

term. Its use to describe a method of skin kayak construction

may be more recent than the method itself, but it’s

helpful in that it differentiates the type from boats

built in the traditional arctic style. The similarities

between boat and aircraft construction are apparent,

and we know which came first. Boats had frames and

longitudinal timbers (and were covered in skins) long

before aircraft were a gleam in Leonardo DaVinci’s

eyes, and even the earliest non-log boats mimicked

the spine, ribs and skins of endoskeletal animals.

The basic methods are old.

Modern fuselage-style skin kayak construction came

into being with the availability of sheet plywood,

which made the getting out of frames a much easier

matter. Rather than construct a five- or six-sided

frame out of as many pieces of wood, each could be

cut out of the plywood in one piece, simplifying matters

immensely. Percy Blandford’s designs were early

examples, and the method had its heyday in the 1950s

and 60s, when my dad and many others ordered plans

and kits from Popular Mechanics.

|

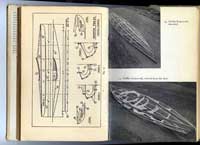

Percy Blandford’s

designs were early examples of modern fuselage-style

skin kayak construction. |

Somehow the method has languished in the intervening

decades. A couple of venerable plans catalogs still

stock vintage skin kayaks, but there are only two

contemporary designs other than my own that I know

of. This is unfortunate in the large view of things,

but on the other hand it affords me the opportunity

(full disclosure again) to scuttle, like an opportunistic

hermit crab, into this unoccupied niche and wave my

flag.

I do not exaggerate when I say that a fuselage-frame

skin boat is the cheapest and easiest way to build

your own kayak. Materials for a basic Egret are less

than $300, much less expensive than plywood or strip-built

kayaks. All wood can be purchased at a lumberyard,

and even if the builder elects to use okoume ply for

the frames, the cost remains within this parameter.

Heat-shrink Dacron is less than $4/yard. Even the

addition of Xynole polyester fabric and epoxy, if

one prefers a laminated skin, does not send the bill

through the roof.

| I do not exaggerate

when I say that a fuselage-frame skin boat is

the cheapest and easiest way to build your own

kayak. |

|

Building a fuselage-style frame is about as easy

as boatbuilding gets. The building jig can be as simple

as a straight 2x6, although the instruction book included

with Egret’s plans shows how to make a plywood

box-beam strongback. The keel is a length of 3/4”

x 1” wood, slotted at either end for the stem

and stern pieces. The frames and bulkheads are easily

cut out using the full-size patterns, then are positioned

on simple uprights and glued to the keel. Stringers

are bent around the frames, glued and screwed to the

stem and stern and also glued to the frames. The bends

are gentle and do not require steaming. Not much to

it, is there? After that, there is the cockpit opening.

Two thin laminates are bent into an oval for the cockpit

carlins. Some steaming is best here, but that can

be accomplished by wrapping the wood in towels and

saturating with boiling water. No need to build any

elaborate steam-box contraption.

|

For the cockpit opening, two

thin laminates are bent into an oval for the

cockpit carlins. |

Egret is not just a rerun of mid-20th-century fuselage-style

kayaks, though. The filleted epoxy joints at the intersection

of every frame and longitudinal permit the use of

thinner plywood and stringers than are found on older

skin boats.

| The filleted epoxy joints at

the intersection of every frame and longitudinal

permit the use of thinner plywood and stringers

than are found on older skin boats. |

|

1/2 inch ply was the standard in the 50s and 60s,

but Egret does just fine with 1/4 inch (6mm). That’s

a significant saving of weight, and thinner frames

permit some flexing while retaining the box-like strength

of the glued joints. One can wiggle the end of a naked

Egret frame as it sits on sawhorses and wonder if

it’s too flexible, but once the skin is attached

and shrunk taut, everything is brought into balance.

|

Once the skin

is attached and shrunk taut, everything is brought

into balance. |

Heat-shrink Dacron is a modern miracle. Anyone who

has wrestled with #10 duck canvas and copper tacks

will appreciate how easily Dacron attaches to the

frame. The fabric is draped over the frame, then pinned

and slit at the ends. The appropriate contact cement

is applied to the stem, stern and to the sheer stringers,

and the fabric is attached. There is none of the hassle

of chasing wrinkles by pulling and repositioning tacks,

as is the case with a canvas skin. Dacron is a lighter

and more pliable fabric, and any minor wrinkles flatten

out when it is shrunk with a common household iron.

Neither canvas nor other synthetic fabrics have the

shrinking capacity of aircraft Dacron, and they are

much harder to work with.

| Anyone who has wrestled

with #10 duck canvas and copper tacks will appreciate

how easily Dacron attaches to the frame. |

|

The addition of a layer of Xynole polyester and epoxy

over the Dacron skin is yet another example of how

modern materials improve the genre. An outer layer

of Xynole adds a bit of weight, but increases the

strength of the skin considerably and provides a high

degree of finish. Sometimes it’s hard to tell

it’s a skin boat because of the smooth, faired

surface. Xynole is known for its abrasion resistance,

and I suspect it would be hard to rip this composite

skin with anything short of a sharpened narwhal tusk.

Hypalon, used to coat inflatables and river rafts,

is another high-strength way to augment the already

tough Dacron.

Put all these innovations together and the fuselage-frame

skin kayak becomes a new creature. I’d call

it a kayak for the 21st century, but that would be

trite. I’d call it a young athlete compared

to an old sack of bones, but that would be unfair

to your father’s skin boat, which, after all,

was a lot of fun. Let’s just say that we have

new ways of doing a fine old thing.

Other articles about skin-on-frame

kayaks:

|