Dragon Wings

by Gary Lepak

Reprinted from Multihulls

Magazine - July/August 1999

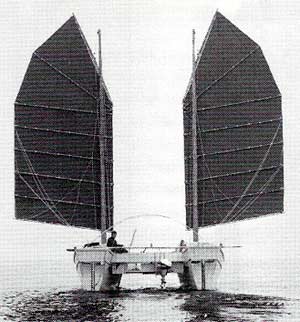

PUFF was a magic dragon that carried our family

of four safely on many adventures... with her two bony wings

spread to the ocean winds. From Alaska to Mexico we rode on

her back and rested in her two hulls, feeling safe and comfortable

in our flights from port to port. Running down dark hallways

of water on a black stormy night in British Columbia, mountains

rising invisibly from the rocky shores on both sides, her easily

furled wings gave us the confidence to go on. Ghosting through

the drizzle of Alaska, we steered comfortably from beneath her

unfurled deck tent or huddled below by the wood stove drinking

hot cups of coffee. Surfing wing-and-wing down two-story high

hills of water at 20 knots off the coast of northern California

may have been frightening, but a drogue off the stern and sails

reefed to the last little panel kept her under control; when

darkness engulfed us, a parachute held her into the seas so

we could rest and wait for morning, to continue. She was our

home in the heat of the Sea of Cortez, her deck a shaded lounge

between the sun and the water. Rounding Point Conception and

beating back up the California coast to San Francisco, she showed

us what she was made of, seeming to revel in the 30- knot winds

and 8-foot seas.

Having a weird boat does get you a lot of attention,

but it's not all flattering. We got used to the powerboats changing

course and buzzing by our stern, camera poised, even the remarks

made by curious critics in little outboards, voices raised above

the din of their motors, thinking we couldn't hear what they

were saying. It's easy to become defensive when your pride and

joy is different from the rest. Many multihull owners know all

too well the stigma associated with the odd boat. Owners of

junk-rigged boats have also seen the underside of many a yachtsman's

nose. But, a flat-sided sheet plywood, homemade, junk-rigged

catamaran with an unstayed mast in each hull? Once, in a quiet

anchorage, I was sitting down below minding my own business

when a beautiful varnished classic yacht slowly circled me.

I overheard the skipper remark to his mate, "If they gave

it to me, I'd burn it!" I restrained myself. Sometimes

the attention was more flattering. Once, drifting in a calm

in the Straits of Juan de Fuca between the US and Canada, a

300-foot Canadian warship, about a mile away, changed course

and came straight toward us, finally coming to a dead stop a

hundred yards off our stern. We stared back at the sailors who

lined the rail staring at us, but they were too far away to

talk to. After about five minutes of wondering what we had done

to warrant such attention, a voice came over their loudspeaker

and boomed out over the glassy water, "Your boat fascinates

me." Then they revved up their engines and made a right

turn leaving us laughing in the swells. During the eight years

we lived and cruised aboard PUFF we were often asked, "How

does it work?" Since I designed PUFF myself, I have no

one to blame for her faults, but I can also take credit for

her abilities. I usually just said, "It works great!"

Some were satisfied with this answer but others demanded more

details: "How does it go to windward?"

Pretty well in good wind - not so great in light

winds. This could have been helped some with a drifter, but

we never

bothered to get one - an outboard works better.

"Doesn't one sail blanket the other on a

reach?" Hardly at all. Since the sails twist very little

and there are no shrouds to chafe against, the windward sail

can be sheeted out quite a ways and still draw. By sheeting

the leeward sail in a bit more than usual, both sails are kept

drawing with the apparent wind right on the beam. The windward

sail seems to feed wind to the leeward sail.

Most people would guess it must be great downwind.

That's for sure! There is no blanketing at all downwind, and

the short, squarish sails are more efficient than tall narrow

sails on this point of sail. Unlike the catboat that suffers

from strong helm when running, our "double cat" is

almost neutral on the helm with the wind on the quarter, both

sails over to one side, and the boards raised. With the sails

out wing and wing it is completely balanced. With the tiller

unattended she'll just keep running downwind.

PUFF was designed for full-time liveaboard cruising

for a family of four. The size and shape of the hulls and the

layout of the deck was initially conceived to be the most efficient

size and shape to contain the beds, seats, storage and living

space that these four people would need. Efficiency here refers

to economical first cost, cheap and easy upkeep, and ease of

handling, more than to power-to-weight and length-to-beam ratios.

Isn't it efficient to save time and money building a boat so

you go cruising sooner with some money in your pocket? Isn't

it efficient to be able to carry a lot of food on board so you

don't have to shop in expensive ports? Isn't it efficient to

carry three dinghies so you don't have someone hollering from

the beach to come and be picked up at midnight in a stormy anchorage?

Isn't it efficient to be able to do all your hull maintenance

on beaches, between tides? Isn't it efficient to be able to

carry three windsurfers? ...well, okay, maybe not, but you have

to be able to get your speed kicks somewhere.

EVOLUTION OF THE DESIGN

Many people asked us how we came to designing and building such

a different boat.

It goes back to when we were living on our first

catamaran, Sea Urchin, a 46' Wharram Polynesian cat that we

built and launched in 1974. During the year and a half that

it took to build Sea Urchin I toyed with the idea of trying

the junk rig, which Wharram offered at the time, but finally

decided against it because Iwas afraid to try something that

I didn't know anything about. Our cutter rig was adequate, but

we didn't like getting the jib down on the bow netting, in rising

winds with cold saltwater splashing up our legs, or tying in

a reef in the main knowing that maybe in half an hour we might

want to take it out again. Also, tacking two headsails was bothersome

in the channels and fluky winds that make up 90% of the sailing

here in the Pacific Northwest. When the weather got rough, flapping

sails and whipping sheets seemed to add to our anxiety. Our

experience led us to the conclusion that with just two adults

and a young child on board, our boat should be the ultimate

in singlehanding ease. On a long passage while one parent is

sleeping, the other is responsible not only for the boat, butfor

the child as well. All these thoughts led us to consider the

Chinese rig as developed by Jock McLeod and Colonel Blondie

Hasler.

After living on our Wharram for a year, we met

a family living on a boat of the same design, but with the stayed

ketch junk rig. We became friends and sailed together for two

months, from Puget Sound in Washington, to Queen Charlotte City

in northern British Columbia. Day after day, we sailed together,

anchoring in the same place at night. It was ideal for comparison

of rigs, and we were very impressed with the Chinese rig. We

were surprised at its windward ability, especially in strong

winds, and we admired the ease with which the sails could be

reefed or unreefed.

We made our tirst offshore passage from the Queen

Charlotte Islands to California, and I started trying to design

"the next boat," that would, I hoped, incorporate

the junk rig. I especially liked the unstayed version that I

had read about, because there was no chafe of the yard against

the shrouds, and the sails could be sheeted out farther. I thought

a trimaran or monohull were the only possibilities for this

rig because the masts have to be stepped in a hull to have enough

"bury" to be self supporting. I sketched quite a few

possibilities but none of them excited us too much. We had become

attached to

the center deck space and the separate cabins of the Wharram

and didn't want to give those things up.

One night, in SanDiego, while talking boat design

with a monohull friend, he asked why "catamaran people"

never put one mast in each hull. I explained that it had been

tried but never really caught on - too expensive, complicated,

narrow staying angles, etc. I knew there must be some reason.

But it got me to thinking, and I realized that with the unstayed

rig there wouldn't be any staying problem, and that the full-battened

lug rig could be made economically ... at home. I sketched some

catamaran designs with shorter, fatter hulls to give us the

accommodations we wanted in a size we could afford, and one

unstayed mast in each hull. The new boat would be between 30

and 36 feet long. It was designed to fit our personal needs:

a liveaboard cruiser for a family of three,

soon to be four.

We tried to sell our Wharram in California but

didn't have any success, so we decided to go to Hawaii. We wanted

to make a "real" ocean passage, see Hawaii and, hopefully,

sell our boat so that we could build our new dreamboat. Seventeen

days at sea brought us into Hilo. I got a job; we stayed on

the Big Island for most of a year; our daughter was born; we

got new sails; butwe didn't sell the boat. So, we sailed for

Lahaina on Maui and there we sold our Wharram. She had been

our home for over four years, and we were sad to leave her,

but it was time for us to try something new.

The time of decision had arrived. Did we really

have the nerve to build that crazy boat with the junk sail on

each hull? Wouldn't it be more prudent to build an existing

design, one that would be sure to work and have good resale

value? I had many misgivings, for sure, but my wife, Joanne,

knew that if we never built it, I would forever be a frustrated

designer, afraid to try something new. She encouraged me to

give it a go. We told ourselves, over and over, all the reasons

why it would work, and a few of the reasons why it might not.

And we figured that if it was a complete disaster we could change

the rig and keep the hulls. So, with our life's savings in-hand

we boarded a jet and headed back to where we had started from

four years

earlier: Seattle.

Having money to build a boat is a lot nicer than

wanting to build a boat and not having any money. The second

time around (years before I promised myself there would never

be a second time) was easier on that point; we mainly had to

worry about getting the boat built, not about making money.

But material cost had gone up more than we realized.

Joanne had to work, now and then, to stretch

the funds out to launching. Also, designing and building is

a lot slower than building from plans. Every detail and all

its consequences must be thought out before you pick up the

saw. We were lucky to discover that Jock McLeod was selling

instructions on how to build the junk rig. We used his excellent

material for designing and building our rig, and I'm sure it

saved us a lot of time and mistakes. The edges of the Chinese

sail are straight, so there is no trick to cutting them.

There is, however, a lot oflabor involved in

making them because of the battens. Anyone who can sew straight

should be able to make a decent junk sail. We made our own,

and they came out quite good.

Our masts were solid grown sticks of Douglas

fir purchased from a yard that supplies utility poles. They

were 35 feet long and cost $85 each (in 1979).

Since there are no tangs, chainplates, turnbuckles,

wire, or winches, the rig is quite economical to put together,

especially if you make your own sails. The halyards, sheets

and lazy jacks call for more line and blocks than usual, but

the total cost is still very much below the usual modern Bermudan

rig with all its wire and winches.

In keeping with the economy of the rig, the hulls

were designed to be built as economically as possible. They

were single chine, V-bottom hulls of sheet plywood and epoxy

with a laminated keel over ply and fir frames and stringers.

The crossbeams were hollow boxes connected to the hulls with

mild steel galvanized fittings, cushioned with rubber (from

old tires) to allow some independent movement and demountability.

The cockpit and centerdeck were suspended from the crossbeams,

independent ofthe hulls so as not to interfere with flexing.

The cockpit seats were, in effect, 12' fore-and-aft box beams

that support the cockpit sole and serve as storage lockers.

An outboard motor swung up in the middle of the cockpit.

The hulls drew only 18", so boards were

needed to prevent leeway. We decided to use dagger-leeboards

on the inboard sides ofthe hulls. They were tied down at deck

level and swung up part way when grounding. Since they were

held against the hull with a steel strap above the waterline,

one board worked on both tacks. They weren't the most efficient

but they didn't take up interior space and they were easy to

maintain. With such shallow draft, the rudders must be deeper

than the hulls. We used kick-up skeg rudders, held by a line

designed to break loose when grounding, allowing the unit to

pivot upwards. They could be pulled halfway up for sailing in

shallow water, or all the way up when anchored for any length

of time.

Each hull had a 12- foot-long cabin behind the

center crossbeam and a double bunk forward. Forward of the mast

was a watertight bulkhead and storage area. The arched tubes

that spanned the cockpit supported a tarp that could be rolled

out for protection from rain or sun, and covered the main cabin

hatches, making it a lot more pleasant to go from one hull to

the other on a dark rainy night. Since we didn't have any head

sails to handle, we eliminated the forward netting on this boat,

allowing us to drop and haul up anchors right from where they

are stored behind the forward crossbeam. On the flat deckspace

forward of the cabins we carried a 16- foot rowboat and a 7

-foot pram, along with 2 or 3 windsurfers.

THE RIG

A year and a half after drawing the lines, Dragon Wings number

one, Puff, was ready to be launched. April Fools Day, 1980 -

we hoped we weren't the fools, but we would soon know. She floated

well. A month after launching the rig was finished and we went

for our first sail. She wouldn't point as high, or go as fast

close-hauled as a sloop, but she got us where we wanted to go

with style and ease. Although a ghoster set flying would help

the windward performance in light winds, we never felt it was

important enough to get one.

After a few sails we got used to handling the

rig (don't pinch or sheet it in too tight) and realized that

it was basically a success. Whew!

The more we sailed, the more we liked it. It

was so easy to make or furl sail that "going for a sail"

became much less of a job than it had been with our cutter rig.

The lazy jacks caught the battens when the sail was lowered,

the excess sheet pulled in, and that's all there was to it-no

hanks, bags or ties. Put on the sail covers and you're done.

Tacking was a one-man, one-hand operation: push the tiller over

and she came about.

If you messed up, you could back the leeward

sail as you would a jib, but after a bit of practice this was

rare. To reef, or lower the sail the desired number of battens,

tie the lowest one down with the downhaul by the mast, and take

in the slack on the line that holds the yard to the mast. There

are no reefties because the batten holds the sail down and the

sheet holds the aft end of the batten down. The sails never

flap when luffed up, but are always docile and quiet. It is

also possible to raise, lower, or reef the sail on any point

of sail.

Dragon Wings was designed for comfortable living

aboard and cruising. She was not a high-speed boat because of

her wide, 7.5 to 1,length-to-beam ratio hulls. She'd do just

8 knots in protected waters, but she'd surf with the best of

them in the ocean when the seas were 8' or more. I'm sure we

hit 20 knots on 20' seas. She's certainly not the type of boat

for someone who can't stand being passed by another boat - most

boats passed her to windward, especially in light airs - but

downwind she'd pass almost anyone not flying a spinnaker. Since

she's meant mainly for ocean cruising, I think the downwind

efficiency and ease of handling are very important. It's rare

that any cruiser makes a passage dead to windward, no matter

how good the boat is on that point of sail, yet downwind ability

is usually "added on" after the rig has been designed

to go to windward. The result is awkward and hard-to-handle

spinnakers, whisker poles, and running twin jibs that can only

be used downwind. On Dragon Wings we used the same sails all

the time and had no sails to store below.

The Chinese rig gybes very easily. The boom is

just another batten, so it doesn't threaten heads too much.

Since there is little twist in the sail and no shrouds, the

sail can be let out all the way when running, so an accidental

gybe is rare

The sheets and sails are over the hulls away from the cockpit,

so in a gybe no one is in the way of the sail. In an intentional

gybe the boat can be brought on to the opposite tack before

the sail starts to swing over, so when it comes to rest on the

new tack, it has lost its momentum and doesn't jerk the sheets.

We lived aboard PUFFfor eight years, cruising

from Alaska to Mexico and have many wonderful memories of those

years. She lived up to our expectations in always being easy

to handle, safe, and comfortable. We were glad that we took

the gamble and tried something different and that when asked

that eternal question, we could always answer,

"Yes, she works great!"

July/August 1999. MULTIHULLS

Magazine