|

|

Bath-tub Steam boats

by Derek Waters

Although just over six inches long, this little tug has a

working 'live steam' engine. With a hull easily carved from

scrap wood, it uses a spirit lamp heating a simple flash boiler.

Once the 'boiler' has been filled with water and the fire

lit the boat will pause for a minute before puttering off

across the bathtub, making the 'putt putt' noise that gives

these boats their name.

Putt-Putt or Pop-pop boats have been around for a long time;

tin toy versions which have scarcely changed in the last century

can still be found in the stores. The undisputed home of Pop-pop

boats on the web is the

Pop-pop pages. Collected there is information on the theory

of (and patents relating to!) pop-pop boats, a list of retail

suppliers and more.

Getting

started:

(click image to enlarge) |

In addition to the wood for the hull, you will need a couple

of copper end caps of the type soldered in place to close

off 1/2" diameter copper piping. They cost pennies at just

about any plumbing or hardware store. Craft shops or model

stores sell the 1/8" inside diameter (5/32" OD) copper pipe

which carries the steam. The same stores will have the thin

brass sheet used for the heat shield 'funnel'. If you have

a choice of thicknesses, 5 mil (0.005") works well.

Building these little boats can be done 'by eye' - the rough

plans shown here (click for a full size version) are intended

as a starting point for your own experimentation. The bold

gridding is inches, subdivided into quarters; print the diagram

as 6" by 8".

The wood used should be light in weight. Where I live, knotty

cedar is sold rough for use as fenceboards. It sands to an

attractive finish, and it's easy to find enough clear stock

for a project as small as this one. Use whatever you can find

locally as long as it is lightweight. Basswood or even balsa

would do. Any waterproof wood glue will work.

Making

the hull:

Square up a piece of wood an inch and a half thick and long

and wide enough to fit your hull. A seven inch length of '2

by 4' will work. From stiff card or thin MDF cut a plan view

template. Mark a centreline as shown. Draw round your template

and flip it across the centreline to draw a symmetrical plan.

Square up a piece of wood an inch and a half thick and long

and wide enough to fit your hull. A seven inch length of '2

by 4' will work. From stiff card or thin MDF cut a plan view

template. Mark a centreline as shown. Draw round your template

and flip it across the centreline to draw a symmetrical plan.

Using a coping saw, bandsaw or jigsaw cut around inside and

outside. The example was cut on a bandsaw - note the cut through

the bow on centreline. Other saws can have their blades passed

through a hole drilled in the waste wood and so will not need

this cut. Once the cut is closed by gluing and clamping it

becomes almost impossible to see.

Once the glue joint at the bow is set, glue the topsides

onto a suitably sized piece of three quarter inch thick

board (nominal '1 by 4'). While the '1 by 4' still has

straight sides, mark the topsides for a sheer line and

cut or sand down to shape. When you are happy with the

sheerline, cut around the outside of the topsides to

remove excess stock. Sand the basic hull to refine its

shape. Note that deck house and boiler weight is concentrated

towards the bow; looking at the plans you will see that

the forefoot of the hull is shown deeper than the run

aft, leaving enough wood below the waterline forward

to create buoyancy to support this weight.

Once the glue joint at the bow is set, glue the topsides

onto a suitably sized piece of three quarter inch thick

board (nominal '1 by 4'). While the '1 by 4' still has

straight sides, mark the topsides for a sheer line and

cut or sand down to shape. When you are happy with the

sheerline, cut around the outside of the topsides to

remove excess stock. Sand the basic hull to refine its

shape. Note that deck house and boiler weight is concentrated

towards the bow; looking at the plans you will see that

the forefoot of the hull is shown deeper than the run

aft, leaving enough wood below the waterline forward

to create buoyancy to support this weight.

|

Drill two 5/32" holes through the hull, one on either

side of the centreline aft, to emerge just below the

waterline. The twin pipes from the boiler will be glued

through these holes later. Once you have checked that

everything fits together as expected it is a good idea

to drill a shallow recess in the deck into which the

lamp can nestle. Otherwise when the motor is running

there will be enough vibration to shake the lamp out

from under the boiler.

Drill two 5/32" holes through the hull, one on either

side of the centreline aft, to emerge just below the

waterline. The twin pipes from the boiler will be glued

through these holes later. Once you have checked that

everything fits together as expected it is a good idea

to drill a shallow recess in the deck into which the

lamp can nestle. Otherwise when the motor is running

there will be enough vibration to shake the lamp out

from under the boiler.

|

|

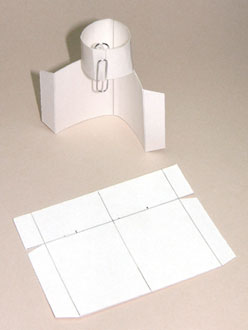

Walls for the deckhouse can be cut from one piece as

shown, or assembled from 5/16 thick 'boards'. A roof

for the deckhouse looks good with slightly more overhang

at the front than at the sides or back. Note that the

hole in the roof for the 'funnel' needs to be large

enough not to touch the metal heatshield.

Walls for the deckhouse can be cut from one piece as

shown, or assembled from 5/16 thick 'boards'. A roof

for the deckhouse looks good with slightly more overhang

at the front than at the sides or back. Note that the

hole in the roof for the 'funnel' needs to be large

enough not to touch the metal heatshield.

|

The

'smoke stack' is cut from thin brass or copper sheeting

with a tubular top section formed by crimping and soldering.

Two and a half by three and a half inches is a good

size, but check against your deckhouse to be sure. Make

a stiff paper or thin cardboard template to check the

fit. Metal sheet as thin as the 5 mil suggested can

be cut with ordinary scissors. The completed 'funnel'

can be attached to the deckhouse with small nails or

tacks. The

'smoke stack' is cut from thin brass or copper sheeting

with a tubular top section formed by crimping and soldering.

Two and a half by three and a half inches is a good

size, but check against your deckhouse to be sure. Make

a stiff paper or thin cardboard template to check the

fit. Metal sheet as thin as the 5 mil suggested can

be cut with ordinary scissors. The completed 'funnel'

can be attached to the deckhouse with small nails or

tacks.

At this point the deckhouse can be glued down onto the

deck and a coat or two of waterproof varnish applied,

but do not attach the deckhouse roof yet. It would be

in the way while fitting the plumbing. |

Propulsion:

The simplest 'pop-pop' motor would be a metal tube, closed

at one end like a test-tube, and filled with water. The open

end of the tube is placed under water and heat is applied

to the closed end. As the end of the tube heats up some of

the water boils into steam. The expanding steam forces water

out of the open end of the tube, and Newton's laws suggest

that whatever the motor is attached to will experience a push.

There's a fuller explanation of the theory available here.

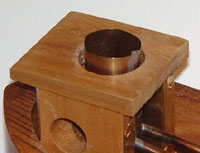

The motor shown without its top on the right here is

slightly more complicated than the test tube example,

but not by a lot. Having two pipes rather than one makes

it much easier to prime the system with water, since

the second tube allows air to escape as water is poured

into the first. Making a 'Boiler' from the end cap for

standard 1/2" copper plumbing pipe allows for a top

in very thin brass shim stock. Once soldered in place

the thin brass can be gently pressed into a dished shape

which will click in and out with each pulse of the motor,

producing a much more dramatic 'sound effect'. At the

left of the picture is an unsoldered lamp as described

below.

The motor shown without its top on the right here is

slightly more complicated than the test tube example,

but not by a lot. Having two pipes rather than one makes

it much easier to prime the system with water, since

the second tube allows air to escape as water is poured

into the first. Making a 'Boiler' from the end cap for

standard 1/2" copper plumbing pipe allows for a top

in very thin brass shim stock. Once soldered in place

the thin brass can be gently pressed into a dished shape

which will click in and out with each pulse of the motor,

producing a much more dramatic 'sound effect'. At the

left of the picture is an unsoldered lamp as described

below. |

As with any soldering job good preparation is key to good

results. Sand the open end of the caps square for a good fit,

and remove any oxidation with fine wire wool before making

the joints. Although I've silver soldered some of these little

motors, soft solder is more than adequate. If your motor gets

hot enough to melt its own solder, it is trying to tell you

something. Plumbers paste flux works fine. Plumbers solder

works too, although it is easier to solder some of the small

joints tidily if you use fine electrical size solder wire.

To make the clicker top for the boiler you will need a little

scrap of very thin sheet brass - anything much thicker than

one mil [0.001"] will be too stiff for the steam pressure

to flex. If there's no thin stock available just use some

of the leftover material from the funnel, or a small copper

coin; your motor won't make the same noise but it will run

just as well.

With the boiler soldered together, test fit it into your hull.

If the boiler is sitting up in the air gently curve the pipes.

The idea is to bring it down to a height where it will just

clear the spirit lamp's wick tube by enough to allow a small

flame. remember that the ends of the tubes must

be consistently below the waterline when the boiler is mounted

in the hull.

It is a good idea to rig up a test for your motor at this

point before gluing it into place in the hull. The test rig

need not be very sophisticated...

|

A source of heat for the boiler is needed. This can

be very basic; a bottlecap full of olive oil crimped

up to hold a cotton string wick will work. The commercially

made tin-toy boats are sold with a bag of tiny little

candles. A simple spirit lamp gives more controllability;

Too much heat is a bigger problem than too little. Time

for another plumbing cap. With its filling tube at one

side and wick on top of the lamp, this one needs to

be placed under the boiler, placing the weight further

forward than is desirable. By placing the wick down

an extended side tube the lamp can be moved further

back, as shown in the plans.

A source of heat for the boiler is needed. This can

be very basic; a bottlecap full of olive oil crimped

up to hold a cotton string wick will work. The commercially

made tin-toy boats are sold with a bag of tiny little

candles. A simple spirit lamp gives more controllability;

Too much heat is a bigger problem than too little. Time

for another plumbing cap. With its filling tube at one

side and wick on top of the lamp, this one needs to

be placed under the boiler, placing the weight further

forward than is desirable. By placing the wick down

an extended side tube the lamp can be moved further

back, as shown in the plans.

|

Wick

can be as simple as piece of cotton string but braided

glass is much more durable. Craft stores sell glass

wick for decorative oil lamps, but it is easy to make

your own from strands taken from a scrap of glass cloth

left over from boatbuilding. If you do not know how

to plait just ask someone with long hair to show you.

The glass braid will do its best to unravel before you

can install it in the lamp, and knots just come undone.

The trick is to dip the ends of the braided section

in to molten candlewax. Wick

can be as simple as piece of cotton string but braided

glass is much more durable. Craft stores sell glass

wick for decorative oil lamps, but it is easy to make

your own from strands taken from a scrap of glass cloth

left over from boatbuilding. If you do not know how

to plait just ask someone with long hair to show you.

The glass braid will do its best to unravel before you

can install it in the lamp, and knots just come undone.

The trick is to dip the ends of the braided section

in to molten candlewax.

|

After a few seconds when the wax solidifies the braid can

be cut to length; the wax will burn off once the wick is installed.

Almost any combustible liquid will burn in these little lamps.

Methyl alcohol (Methanol, Methyl Hydrate, sold as fuel for

fondue sets amongst other things) works well and is reasonably

safe; just do not get it near your mouth since it is very

toxic.

Two

squeezy bottles or syringes will be useful; one to contain

fuel and the other for priming the boiler with water.

To start your finished boat first fill the lamp and

trim the wick to length. Set the lamp aside unlit and

hold the boat so that the open ends of the pipes from

the motor are facing upwards. Gently pour water into

one pipe until it flows out of the second pipe. Tilt

the boat around to be sure there are no air bubbles

inside the boiler. Place a finger over the ends of the

pipes to prevent the water running out and set the boat

in the bath; the ends of the pipes must stay under the

water surface. Two

squeezy bottles or syringes will be useful; one to contain

fuel and the other for priming the boiler with water.

To start your finished boat first fill the lamp and

trim the wick to length. Set the lamp aside unlit and

hold the boat so that the open ends of the pipes from

the motor are facing upwards. Gently pour water into

one pipe until it flows out of the second pipe. Tilt

the boat around to be sure there are no air bubbles

inside the boiler. Place a finger over the ends of the

pipes to prevent the water running out and set the boat

in the bath; the ends of the pipes must stay under the

water surface.

|

Place the lamp into position and light it. After a minute

or so you may see a few bubbles escape from the ends of the

pipes and shortly after that the motor will start its cycle

and your boat will be on its way with a 'pop pop pop'.

Derek

Waters

|

|

|

|

|