Sailing

on the Seas of Time

by Bob

Means

I checked into Mitchell’s

guesthouse in St George, Grenada, one block off the embarcadero.

A clean block structure on a narrow hillside road. Tile floors.

Mr. Mitchell died fourteen years ago, but not before building

the guesthouse from money he earned working in Aruba with an oil

company. Mrs. Mitchell now provides for herself and her two daughters

who do the cleaning and change the sheets. It takes four strokes

on the handle to flush the toilet plus the showers across the

hall were cold. A unique blend of concrete, tile brick and rod

iron railings. Nescafe instant coffee with inspirationals on the

bedside table for breakfast.

Mitchel's

Guest House

Mitchel's

Guest House |

Before turning in, I returned to

the dockside to find the Adelaide B, the cargo schooner I was

to take to Carriacou. In my search ,I was accosted by Maurice,

a young man who thought I was looking for drugs. When I told him

I was looking for the schooner Adelaide B, he was totally confused.

I told him it was the schooner that hauled cargo to Carriacou

on Tuesdays and Saturdays. Then his faced brightened up as he

told me, “Come”, and escorted me to an old shrimp

boat named Alexis. I again told him, “No, not this one”,

whereupon he began to argue with me that this was the boat that

delivered cargo to Carriacou. Once again, I had to inform him

that it was a sailing boat. A crew member of the Alexis pointed

down the dock where we both looked and saw the Adelaide B. He

looked amazed, and then acted like he knew all along.

Carriacou work boats under sail

- that’s why I came. I had heard of the thriving sailing

fleet, fishing off the waters of Carriacou. Having my own fleet

of fishing sailboats in Nicaragua, the idea still holds much fascination

as to how others do it and make a living. I know the struggle

first hand as I watched my own little fleet go down to defeat

after six years of scrapping and trying as hard as I could to

hold it together. News of this fishing sailing fleet came to me

as I looked for a place to winter after suffering a cold winter

in my new home, Virginia. After twelve years in the tropics I

just can’t adjust to the cold after 53 years and an arthritic

foot. And six months without sailing for me is just too much to

bear.

Maurice found the Captain and introduced

me as if he and the Captain were old school chums. I told Captain

Bully, a very large 24-year-old West Indian fellow, that I was

interested in sailing with him to Carriacou. The Adelaide B was

not really a schooner but a sloop, but here they call all cargo

hauling sailboats schooners. Someone tried to explain that to

me but I never quite got it. I told Captain Bully I wanted to

study and do a story on workboats, his boat included. He was unmoved

and told me it would be twenty-five dollars. The advertisement

on the Internet said 20, I guess it had gone up since then. I

noticed that there were no sails hanked on, and I asked if we

would be sailing to Carriacou. He informed me that the sails had

ripped in the last storm, and that he had been motoring. I asked

how long ago that happened, and he told me his father had retired

two years ago, and he had taken over the boat. He never actually

said, but the impression I got was that not a sail had been raised

since he taken over the boat. I was greatly disappointed but determined

to carry on. I was told to be back at the boat at 8:30 am as they

would leave at nine. Maurice wanted to show me the rest of the

town after he bought me a beer. I was taken back that he bought

me a beer, and I wanted to return the favor. He said could I please

just give him the money for a beer, but all I had was a ten-dollar

note. I gave him the note on the promise he would be at the guesthouse

at six the next morning with the change.

In the morning after settling with

Mrs. Mitchell, I headed for the wharf. No Maurice was to be found.

I arrived at 8:30 am, and cargo still being loaded - plywood,

lumber, drums with some type of liquid, boxes of various sizes,

even cards and letters. Large propane bottles were loaded on deck

and one dropped prematurely, jarring the valve, propane spraying

wildly, the crew fleeing in every direction. One brave soul secured

the valve to laughter - a good thing no one was smoking. Ten o’clock

we set sail to the hum of the 360 Cat diesel for the four hour

journey to Carriacou and then on to Petit Martinique. As we left

St George Harbor, Grenada numbers of sailing boats were motoring

in for the big Regatta of the year. Although I love a good regatta,

I wasn’t disappointed, my mission being the dynamics of

the work boat fleet. My feelings were a bit arrogant, thinking

of all those frivolous plastic boaters when I had real life situations

to observe. How was I to know of the importance of the local regattas

in keeping the working fleets alive and motivated.

The trip from Grenada to Carriacou

was gruesome. The wind was blowing 35+ right on the nose, and

as we plowed through the waves, the decks were awash. So much

for my nostalgic cruise on a sailing cargo hauler. After the first

30 minutes, I realized I had lost my sea legs and needed to lie

down. The only place to lay was on a 2x12 nailed to the outer

bulkhead. I lay down for only a minute before being thrown on

the deck. The only way to hold myself in place was to wedge this

toilet seat on rollers between the inner bulkhead and me. So there

I lay for four and a half-hours trying to resist the urge to be

sick. As we came leeward of Carriacou things began to settle down

a bit, I finally got out on deck only to be confronted with Capt.

Bully who demanded his twenty-five dollars. I felt a bit jaded

and was wondering if this was a sign of things to come. Even tying

up to the Carriacou dock was no easy task as the wind was blowing

so hard the crew struggled with the lines. I’m sure the

crew downing three bottles of rum during the trip didn’t

help much, but then again I thought maybe that was the ticket.

Another observation of the crew which was a total surprise to

me was the constant use of cell phones. We in the death throngs

of tradition, I thought.

"I

cried out from the street two or three times. ‘Billy Bones!’"

Hillsborough

Hillsborough

|

Leaving the Adelaide B with no

farewells, I began asking for the whereabouts of John’s

Unique Resort in Hillsborough, the largest town on the island.

I found the place with not too much trouble after asking a few

of the people on the dock. After checking in, I noticed a couple

sitting on the patio. Asking if they were staying there, I received

the reply that they were the owners. I stated, ‘you’re

John then’, to the answer of ‘no I’m Joseph

Johns’. I asked if he knew a guy named John Smith the skipper

of the ‘Mermaid’ one of the oldest work boats on the

island. His answer was ‘Yes, everybody knows John Smith’,

a very crazy guy, he’s always around somewhere’. I

had arranged to meet John Smith via the Internet a couple of weeks

before. John Smith told me to contact him via VHF channel 16.

I was directed to the police station where they had a VHF. I hailed

him all the rest of the afternoon to no avail. A passerby who

overheard me informed me that Smith had been seen that morning

sailing his little dory in Tyrell Bay. I hired a taxi at ten US

dollars for Tyrell Bay. I was told at the French restaurant that

the Mermaid wasn’t in port, but to check with Billy Bones,

another American guy who runs the Windward Marine store. He lived

up the hill next to the butchers.

I cautiously approached what I

thought was Billy Bones's house, hearing American voices and the

sounds of American football on the television. I cried out from

the street two or three times. ‘Billy Bones!’ feeling

a bit stupid. No answer from the street when the guy next door

said ‘Yah, that’s Billy Bones, go on in’. Opening

the gate and walking to the front porch I knocked on the door.

Yep, there stood Billy Bones. Guy in shorts held up by a safety

pin, glass eye, four days growth of beard, ruddy complexion that

comes with spending years on the sea exposed to the sun. I introduced

my self ’I’m Bob Means, I’m looking for John

Smith, I’m doing a story on the workboats of Carriacou‘.

Instant connection. ‘Hey great!’ was his response,

“come on in, you want a beer?’

We jabbered on for about fifteen

minutes along with Bones’ friend Clyde Sanda, sharing experiences,

even knowing some of the same people. Apologizing that I was interrupting

their football game, I was invited to stay and watch. I explained

with concern that I needed to find this guy named John Smith.

Bones took me out to his overhanging porch that looked over Tyrell

Bay and pointed out John’s boat the ‘Mermaid’.

Said his dinghy was along side and that he should be coming up

soon to watch the game, as Bones had invited him earlier in the

day. As I looked out over the bay I noticed at least twenty or

thirty cruising yachts, a mixture of catamarans and monohulls,

and thought, for the cruising crowd, this must be paradise. Returning

to Bones living room, I settled down with my beer and began to

enjoy the game. We all gave running commentaries; after all it

was the playoffs.

At half time, we wandered back

out to the porch to see what John Smith was up to. I noticed a

small double-ended dory sailing with cat spritsail toward the

dock at Carriacou Marina. Bones said that was John Smith and that

neither he nor John had an engine, and neither have had since

their launchings 32 years before. John had bought the Mermaid

25 years ago from Zephrine Mclawrence, who was the builder for

Lynton Rigg. When Linton Rigg had died in 1964, he willed the

boat back to Zephrine.

|

Linton Rigg was single handedly

responsible for the renaissance of boat building on Carriacou.

He retired from Burgess & Rigg Marine Architects and Builders

of Massachusetts in the late 50’s, and made his way down

to the southern Caribbean. On his arrival on Carriacou the economic

conditions of the Island were almost at a standstill. The modern

day cruisers now find a paradise, but for the islanders who live

and work there, life has always been a struggle. Even as far back

as Columbus, the goal was not to find paradise but economic gain.

Disease, shipwreck, starvation and continual military conflict

were the order of the day for hundreds of years. The first to

try and settle in the Grenadines after disease virtually wiped

out the native population were the Huguenots who were seeking

refuge from the French inquisition. Soon the islands were traded

back and forth in military conflict between the Spanish, French,

Dutch and English. Nutmeg became the gold of Grenada. Small plantations

of sugar and cotton soon followed on the other islands, which

meshed the European, and African cultures. Although there were

a few cotton plantations established on Carriacou, the mainstay

of economic development became shipbuilding when the English Crown

sent Scottish shipbuilders in the late 1700’s to build sailing

ships to service the inter island trade and fisheries. The local

timbers were ideal for this industry. The names are evidence of

this migration as the present day shipwrights are McLewrance,

Stewert, McFarlane, Compton and McDonald. The reputation of these

shipbuilders survived even up until the early 1900’s when

a harsh economic climate along with the convenience of steam took

their toll.

To re-ignite the maritime tradition

on Carriacou, Rigg set out designing the ’Mermaid’.

She being 44’ on deck, 56 over all, 36 at the water line,

13 foot beam, 7’ draft aft and 4.5’ forward. She carries

5-ton internal ballast with her mast height being 44’, boom

at 24’, being a gaff rig cutter her gaff is 19’. Due

to her inside ballast she would be considered a workboat being

that the difference between a yacht and a workboat is inside and

outside ballast. In his design Rigg combined his Bermuda boats

with the local boats to come up with what they now call ‘deck

boats’. He established the workboat regatta with $500 prize

money for first place, his idea was that the competitive spirit

would do more for the local economy than anything else would and

he was right. ‘Mermaid’ won the first regatta as with

the next nine consecutive years but soon after one could see signs

of other boats taking shape to beat this new comer. To support

themselves in this new kindled spirit they used their boats to

fish and haul passengers and cargo.

Clutching his chest, John Smith

slowly made his way up a trail that led to Bones’ cliff

side dwelling. I introduced myself and what I was intending. As

with Bones, John and I connected instantly. The conversation swayed

from similar maritime adventures, mutual acquaintances, and wartime

experiences in the Vietnam War,. As we settled back to watch the

Rams and the Eagles, cheering on our favorite team with expert

commentary, me being the only Ram fan. Local history was brought

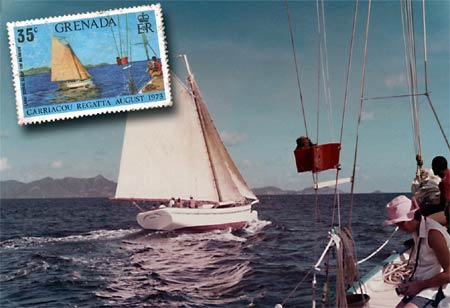

to light along with the significance of the ‘Mermaid’

and how she revived local traditions and reestablished the fishing

industry using sail. ‘Mermaid’ was so popular they

even put her on the 35 cent stamp of Grenada (see picture below).

In the midst of all the hooting and hollering, bragging and outright

lies, John and I settled on a three day cruise aboard the ‘Mermaid’

to some of the outer islands. He also explained to me how the

night before he struggled all night to pull this cruising yacht

off a reef they had landed on and had had sharp pains in his heart

ever since. All of us being in our 50’s, I mentioned that

was not a good sign, something he should look into which he agreed

to do.

John and I agreed to go out for

three days. First I wanted to go to the Windward side of the island

and check out the boat building and fishing community that I had

heard so much about. There were no boats being built at the time

I was there, but I met with a few of the fisherman and found out

they go out everyday, and when I was ready they would take me

along. I met one fellow named Benson who was working on his boat

down on the beach. Hundreds of boats from 6’ to 110’

had been built on this beach among the tangle of trees and mangroves.

Benson had won the Bequia Regatta the last year in the stern boat

division. Stern Boats were developed for whaling, which still

goes on in the area. The story is that an old New Bedford whaling

man settled in Bequia after he tired of the whaling ships. He

married one of the local girls and set to building whaling boats

that became known as Stern Boats. They are double ended, about

30’ long with a 10’ beam, sprit rig with a dagger

board. These boats get sponsors to help support them during the

regattas, and they also win prize money.

"As

we came around to gain steerage

we couldn’t see how we were going to miss it..."

Back in Tyrell Bay the next morning,

I met John Smith by the market encouraging one of the locals restoring

the grill and headlights of his van. All the parts came from other

models, but I’m sure he got it to work. We headed into the

market to buy all the provisions for the three-day trip. John

put some kind of tuber that I’ve never seen before, plus

sweet potatoes on the counter. Grabbing a bag of flour I was informed

of his expert bread making capabilities, he then looked for dried

fish. Paying the bill of 80 ec dollars (about 30 USD) we divided

up the four plastic grocery bags and headed for his 6’ wooden

double ended dory anchored twenty feet off the beach. I was then

informed that he never beaches his dory because it is much too

fragile. Rowing out to the ‘Mermaid’ we were met by

Winger, Johns’ little black dog that looked something like

an 8” high Husky but with no tail. The way he was carrying

on, one would have though he had been abandoned for a month. I

was shown where I was to bunk, and stowed my gear as John put

away the provisions. The one thing left to do before we got under

way was to transfer water from five-gallon plastic water containers

to one-litter plastic coke bottles. John catches all his water

using a rubber awning covering his aft deck where he has attached

a rubber hose in the middle. As it rains he places one of the

five-gallon containers under the hose then transferring the water

to the coke bottles which he stows under the sink in the galley

for easy access.

‘Mermaid’ was truly

my dreamboat. She was of workboat construction with her thirty-five

years showing. On her deck was paint of various colors. Corners

of the deckhouse showed many years of use and change. The framing

for the aft deck awning was of rough-sawn timber nailed to the

frames that supported the kickboards. The cap on the transom was

missing due to construction in process. Inside the Mermaid was

a web of wires attached to non-uniform switches that ran lights

and pumps. The head was a five gallon bucket tucked up the fo’c’sle,

and an array of anchors littered the foredeck. When I asked John

about all these anchors, I was told that to have a boat with no

motor it’s important to be able to stop. Even with no wind

you will still have strong currents through the islands. He explained

that he had plowed into a few islands, along with a number of

other mishaps, so he carries: a 55 pound delta with 125’

of 1/2” chain as his working anchor; a 60pound plow (cqr)

as a backup with 125’ of 1/2” chain; a main Kedge

hanging on the port cat; a fisherman on 3/4’ nylon; a main

bower of 275 pounds, and he also has below a 35 pound Danforth

plus two 100’ foot lengths of 3/8” chain. Mermaid

is a gaff cutter, mast height of 44’, boom 24’ and

gaff of 19’ and she carries approx. 900’ of sail.

With all pre-sail chores complete,

it was time to hoist anchor and set sail. Mermaid has a hand crank

windless, and I was told to tail the chain wrapped three times

around the drum and help crank whenever possible. One can’t

be in a hurry with this arrangement, and I was told slow and easy.

About half way through this process I began to wonder how John

handled this all by himself. He said there were times when he

had to abandon his anchor, set it to a buoy, and come back to

fetch it with some help. When the anchor was finally free, John

set both headsails, and I was sent back to the wheel with the

command hard to starboard. Of course me being a tiller guy I went

hard to port, just when I caught my mistake so did John with a

repeat of the command being a little more forceful. Even though

there were thirty boats in the harbor, there was only one we had

to be concerned about which happened to be a huge motor-cat ferry.

As we came around to gain steerage we couldn’t see how we

were going to miss it, since we had no motor. All we could do

was stand there and wait to see what would happen, this could

be a very short cruise. My thoughts went from, there is no way

we are going to clear to well maybe. In the end we cleared the

forepeak of the starboard hull by maybe four inches. No comment

as John and I looked at each other and we began to hoist the mainsail.

Hours later the near miss became the topic of conversation as

it did numerous times after.

It’s

always difficult getting use to someone else’s boat, especially

one with as much personality as the Mermaid. Trying to get used

to halyards, topping lifts, and sheets can be trying, not only

to the captain who knows his boat like the back of his hand, but

more so to new crew. John explaining things he usually does single-handed

can expand the range of patience. This cruise was no exception.

With the wind doing 30 knots plus, it was a relief to finally

have all sails set and sit back under the aft awning and watch

Mermaid sail unattended through the waves. John set all the trolling

lines in anticipation of catching a tuna, Wahoo or kingfish. Our

course was set for Chatham bay on the lee side of Union Island.

Winger snuggled up against my hip to steal a few friendly strokes

of his fur. John began the conversation by expounding on his thirty-five

years at sea, twenty-five of those on the Mermaid. It’s

always difficult getting use to someone else’s boat, especially

one with as much personality as the Mermaid. Trying to get used

to halyards, topping lifts, and sheets can be trying, not only

to the captain who knows his boat like the back of his hand, but

more so to new crew. John explaining things he usually does single-handed

can expand the range of patience. This cruise was no exception.

With the wind doing 30 knots plus, it was a relief to finally

have all sails set and sit back under the aft awning and watch

Mermaid sail unattended through the waves. John set all the trolling

lines in anticipation of catching a tuna, Wahoo or kingfish. Our

course was set for Chatham bay on the lee side of Union Island.

Winger snuggled up against my hip to steal a few friendly strokes

of his fur. John began the conversation by expounding on his thirty-five

years at sea, twenty-five of those on the Mermaid.

John’s life began on Long

Island Sound where he sailed as a youth. He says he never really

recovered from the stint in the U.S. Navy as a corpsman during

the Vietnam War. His work on a receiving ship trying to patch

up young Marines, many who never made it, became more than he

could bear. After his honorable discharge he tried to regroup

in his home waters, but memories continued to plaque him, so he

headed south. He crewed on numerous boats and finally ended up

in the southern Caribbean with the Mermaid. Mermaid became his

full time occupation. He started by chartering and took on shore

time jobs when the opportunity presented itself in order to purchase

new sails, rigging, and all the other demands of an older wooden

boat with no engine. We talked of loves won and lost, and the

one he has never recovered from, a beautiful Norwegian girl he

ended up following to Norway. The cold was too much for him, so

he returned to the warmth and comfort of the tropical sea and

his beloved Mermaid. John has had two rum bottles broken over

his head and fended off a knife attack from another anguished

vixen, been kicked out of numerous bars, pubs and marine establishments,

some that he’s not allowed back into even now. John has

become a crusty ol’ sea captain in his 55 years, and one

of the best boat handlers I’ve had the honor of sailing

with. Our three-day cruise took us to Union Island and to Saline

Bay, on Mayreau. We returned to Tyrell Bay just in time to watch

the Super Bowl with Billy Bones and Clyde.

"...a

tall attractive Dane with pronounced Nordic features,

the kind many a Viking would have gladly sacrificed his life for."

Billy Bones owns and operates Windward

Marine and is a true product of the sixties. Now pushing sixty

himself, his politics have never faltered, still believing the

flower generation should rule the earth. After years of boat deliveries

and traveling the earth, he is truly settled in his island home.

History is Billy’s passion, and it’s a true pleasure

listening to his discourse of island lore. He has designed his

chandlery to service the wooden fleets of cargo hauling and fishing

fleets out of the concern that to lose this tradition would make

this planet a lonelier place. He single handedly organizes and

maintains the working boat regattas, donating much of the money

and also raising funds from other sources. He agrees with Linton

Rigg - if we stop the regattas, we lose the fleet. When I told

Billy of my desire of going out fishing with one of the work boats,

he said ‘Hope McLewrance of ‘Imagine’ is the

guy you want to go with; he is the best fisherman in the fleet’.

He then told me of Dave and Ulla Goldhill who run the Bayaleau

Point Cottages, and who know all the fisherman extremely well

on the Windward side. They would be a help if I needed some assistance.

So I gathered my gear and grabbed the bus to Windward. I told

the bus driver I was looking for Dave and Ulla’s place,

and although it was out of his way, he drove me right there.

Dave and

Ulla

Dave and

Ulla |

When I arrived Dave was out with

his hand built motor launch doing a dive charter. As I wandered

through the well manicured garden of tropical plants and fruit

trees of the Bayaleau Point Cottages, I ran into one of the guests

from the UK. He directed me to the Goldhill home. Ulla greeted

me, a tall attractive Dane with pronounced Nordic features, the

kind many a Viking would have gladly sacrificed his life for.

Ulla found her way here via schooner from Denmark. She and her

crew bought goods in Trinidad to sell among the islands in the

southern Carib Sea. After meeting Dave Goldhill in one of the

many Rum shops, they settled down together. Along with raising

their three children, they established the cottages of Bayaleau

Point, the dream of many a sailor who has grown tired of the confines

of his ship. Bayaleau means bay of water, and it is where the

ships of old would come to replenish their water casks. The original

well is still active. Over a cup of coffee I told Ulla I was looking

for Hope McLewance . The Goldhills have been friends of Hope for

many years, and Ulla crews on the Imagine during all the regattas.

After getting settled into the 14’ by 14’ Yellow Cottage

with mosquito netting on the double bed, and a veranda overlooking

the citrus orchard, Ulla directed me to Hope's home in Windward

- about a mile away down the shore drive.

I met Hope outside cleaning the

yard where he lived with his cousin in their seafront concrete

home. When I told Hope I was studying the working fleet, and that

I had developed one myself in Nicaragua, he invited me in for

a beer. We sat at the table overlooking the bay. I asked how he

had started fishing. He said as a young boy he used to take out

his family’s home built 14’ sailing skiff to Tobago

Cay for days at a time. Tobago Cay is now filled with cruising

sailors, but when he was young he would be the only boat there.

He would sun dry his catch, and then sail his little boat to Grenada

where he would sell his fish. He said his mother would worry about

him being out for days at a time never knowing for sure if he

would return. Finally his mother talked him into moving to England

to live with relatives to look for “real work“. He

lived in the UK for 21 years, first finding work in a brewery

and then running a laundry. His desire for fishing and the sea

never left him. After raising two sons he returned to Carriacou,

and with money earned bought the locally built 37‘-deck

sloop “Imagine”. He has been sailing and fishing ever

since. He says you can make a living fishing, but one has to work

hard. Hope prefers to go out for days at a time; he says it’s

easier that way than coming in every day. I asked if I could crew

with him in the morning, and he agreed over a second bottle of

beer.

When I returned to the cottages,

I met Dave Goldhill as he was cleaning up from his days dive.

After 18 years on the island he has become a member of the culture

but not without paying his dues. He started out as a commodity

trader in Manhattan, New York, and soon tired of that and found

his way to the Caribbean. He linked up with John Smith, and for

three years sailed the Mermaid doing three circumnavigations of

the Yucatan, eventually settling in Carriacou. He began here by

sailing and fishing with Hope in the Imagine which hardened his

bond with the local maritime crews. Dave says it was a hard life,

many times ending up with 20 ec (8 usd) after buying a pack of

macaroni and two beers. He now looks back at that time with fondness,

remembering when even as late as 1984 you could hardly find a

cruising yacht along the shore and it’s numerous anchorages.

He also crews with his wife Ulla and friend Hope during regatta

day. Dave says the week before regatta all the fisherman spruce

up the workboats to be presentable for race day.

The next morning at six thirty

Dave drove me down to meet with Hope and his crew, Gordon. Both

Hope and Gordon are well into their 60’s but hardly miss

a days fishing. We all jumped into the six-foot skiff for a short

row to the Imagine, lazily at anchor. Hope and Gordon wasted no

time setting sail and getting underway as the other boats were

a bee hive of activity, all wanting to be the first boat to leave.

The competitive spirit runs ripe with all crews. Who can be the

first one out, catch the most fish and race back to port. Once

outside the reef Hope threw out his trolling lines to fish as

we made our way fifteen miles out to the fishing grounds off Saline

Rock. It wasn’t long before we were hauling in a barracuda,

the first catch of the day. Sailing for two and half hours and

finding the right spot, Gordon dropped the head sail, attached

a preventer to the end of the boom which held it hard to starboard.

With the helm secured hard to port, we were hove too and started

drift fishing with hand lines. Gordon went forward, me amidships,

and Hope fished over the transom. It wasn’t long before

Hope was hauling in three Butterfish at a time. A butterfish is

a bright red with blue spots and is related to the Grouper family.

They get about a dollar fifty US a pound for it from the local

buyers. They get a buck seventy-five for Barracuda.

As the day went on, the conversation

went from boat building, fishing, and of course of John Smith

and his loves won and lost. He was a bit worried that he would

have enough to careen the Imagine so he could do the repairs needed

and paint the bottom. Hope told me the boat builders on Bequia

were the best. He told me the story about how a 109’ schooner

built and crewed by Bequia boys ran aground on the reef near Tobago

Cay, ripping off part of the keel. They filled the hold with 55

gallon drums, hauled the schooner off the reef, turned the ship

upside down while at sea, repaired the keel then righted her,

pumped her dry and sailed away. An amazing feat, but not surprising

for those who build their boats on the beach among the tangles

of mangroves.

At

three-thirty, not having as much success as Hope and Gordon, it

was time to head in so we could make it before dark. There were

about sixty pounds of fish on the deck. As we raised our headsail

I noticed all the other boats doing the same for the race homeward.

There are nine boats in the Windward fishing fleet with the names

Imagine, Margeta O, Pipe Dream, Chalib Sea, Glacier, Mary Stella,

Rosalina, American Dream and Run Away. As we sailed in, I reflected

on a hard days work fishing hand lines, the struggle of surviving

in what many consider paradise. Upon arrival. We sold our product

and secured the boat. I thanked Hope and Gordon for a great day,

and made my way back to Dave and Ulla’s for a promised dinner

with the rest of the guests at the cottages. I could hardly keep

up the conversation, as I was beat from the day’s activity

and looking forward to my nice bed in the yellow cottage. At

three-thirty, not having as much success as Hope and Gordon, it

was time to head in so we could make it before dark. There were

about sixty pounds of fish on the deck. As we raised our headsail

I noticed all the other boats doing the same for the race homeward.

There are nine boats in the Windward fishing fleet with the names

Imagine, Margeta O, Pipe Dream, Chalib Sea, Glacier, Mary Stella,

Rosalina, American Dream and Run Away. As we sailed in, I reflected

on a hard days work fishing hand lines, the struggle of surviving

in what many consider paradise. Upon arrival. We sold our product

and secured the boat. I thanked Hope and Gordon for a great day,

and made my way back to Dave and Ulla’s for a promised dinner

with the rest of the guests at the cottages. I could hardly keep

up the conversation, as I was beat from the day’s activity

and looking forward to my nice bed in the yellow cottage.

I understand why Capt Bully would

rather motor than sail, how easy it would be to forego sailing

for power, to allow the ongoing traditions of Carriacou to become

just another chapter in history books. To make it happen is a

struggle. For Billy Bones, John Smith, Dave and Ulla, Hope and

Gordon and all the others of the sailing work boats of Carriacou

it’s a choice they make to keep tradition alive. As I was

leaving Windward, I passed by the graveyard with many headstones.

One of a man named Bernard Stewert caught my attention. Along

with his name was the etching of a schooner named the Gertrude

B. Above the etching was inscribed “Sailing on the Seas

of Time”. In Carriacou they all truly sail on the seas of

time. |