A pod of dolphins have taken up residence off the southern coast of

the Boso Peninsula, Yamazaki said, and showed me the pictures. They were

underwater shots of bottlenose dolphins, taken by a kayaker.

Underwater shots? Yes. He'd find the dolphins, usually only a kilometer or

so offshore. Then he'd capsize the kayak, take his photos, and eskimo roll

upright again. Simple.

I was intrigued.

Now, I've been a sailor for more than three decades, but I didn't take up

diving or skiing until I turned 50. Ok, so I'm 58, so why not become a

kayaker? All I need is a kayak.

Right.

Right.

But that's how my mind works.

A quick tour of kayak shops showed me that FRP and carbon fiber boats were

anywhere from $2,000 to $5,000 each. So I decided to make one. As it was,

I got things backwards. I'd had good luck with Glen-L boat designs in the

past, so I checked out their website for kayaks. There it was, Seakayak.

Unfortunately, marine plywood is not a domestic product here in Japan, and

a 4 mm imported sheet costs nearly $100. So I decided to order the

Seakayak kit from Glen-L.

Only after the ordering was done did I get three books of kayak building.

Had I gotten the books in advance, I may have opted for Chesapeake Light

Craft, but that's spilt milk.

With the kit on its way, I went to the System Three website for epoxy,

gloves, stir sticks, fiberglass tape and cloth, and the other miscellany I

needed.

The ingredients arrived en masse. First the seakayak kit, in two boxes.

Then the epoxy stuff from System Three.

The ingredients arrived en masse. First the seakayak kit, in two boxes.

Then the epoxy stuff from System Three.

I have no covered space at my tiny home, so I coerced a good friend into

letting my build the seakayak in his garage-storeroom. If we built it

cattycornered, the 17-foot kayak would fit.

Tetsu and I used the box the kit came in as a table, setting it up on some

boxes. We laid out all the plywood parts and commenced giving the two

coats of thinned epoxy each. (Why thinned epoxy? Ordinarily, if I had been

living in the U.S., I would have used System Three's Clear Coat epoxy, but

because it is toxic, it cannot be shipped by air to Japan. Talking to

System Three about the problem, they suggested that we thin the regular

epoxy out with 10% lacquer thinner to get a similar penetration to the

thin Clear Coat.)

We started this process as the winter began, so whenever we used epoxy, we

had to leave it for 24 hours to cure. Talk about slow work. Turned out OK,

though, because I would stop by the garage early in the morning before

work and slap on some epoxy (dressing up in a Tyvek suit so I got no epoxy

on my clothes). Next morning when I arrived, the job would be cured.

After the plywood parts had their epoxy coats, we used butt blocks to join

the side planks and bottom planks. At last, we could start sewing the

kayak together.

After the plywood parts had their epoxy coats, we used butt blocks to join

the side planks and bottom planks. At last, we could start sewing the

kayak together.

Well, almost. First we had to drill a bunch of holes in the planks. Actual

stitching took only a couple of hours.

Viola. The seakayak suddenly looked like a boat instead of a pile of

epoxy-coated plywood.

Actually, it reminded me of Frankenstein's monster, all stitched up with

copper wire like it was.

Isn't it funny how you want to get out on the ocean the moment there's a

boat in front of you? So what if it's just stitched together. So Tetsu and

I decided we'd better take kayaking lessons.

The very next Saturday saw us on the beach at Hayama, sun shining in a

cold blue sky with a wind chill that felt like thirteen degrees below

freezing. But we stuck it out, learned how to paddle, strived to keep the

kayaks from tipping over in the cold water, and found out that even

novices can paddle these slim crafts through good-sized waves without

capsizing. We went back to building with renewed fervor.

Time

to glue the hull together. We thickened the epoxy with cotton fibers and

shoveled it into a plastic bag that we'd clipped a corner out of. Tetsu

squeezed the thick epoxy mix into the joints and I came along with a

tongue depressor and rounded out the fillets. Then, once the fillets had

cured, we could pull out the copper wire and smooth down the fillets,

readying them for taping. Time

to glue the hull together. We thickened the epoxy with cotton fibers and

shoveled it into a plastic bag that we'd clipped a corner out of. Tetsu

squeezed the thick epoxy mix into the joints and I came along with a

tongue depressor and rounded out the fillets. Then, once the fillets had

cured, we could pull out the copper wire and smooth down the fillets,

readying them for taping.

At this point, we installed three-quarter inch carlins along the sheer and

glued some of the same stock across the tops of the bulkheads where the

decks would lay.

I cut a bunch of 4-inch glass tape and laid it over the kayak, ready to

install. With a paper cup of epoxy in hand, I painted a length of seam,

then laid the fiberglass tape over that, and wet it down with more epoxy.

I worked down one side; Tetsu took the other. Between the two of us, the

hull and bulkhead joints were taped and epoxied in just over half a day.

Progress.

Time to get more supplies. This time I went to the Chesapeake Light Craft

website and ordered yellow and red paint, high solid primer, a block of

closed cell foam, a kayak seat, a back pad, and two bronze pad eyes for

bow and stern.

We

turned the kayak over and taped the outside seams with two layers of

4-inch tape, offset so each layer overlapped the joint by one inch. We

gave those seams three coats of epoxy, building up enough so sanding would

eliminate the tape shoulders. Worked pretty well. We

turned the kayak over and taped the outside seams with two layers of

4-inch tape, offset so each layer overlapped the joint by one inch. We

gave those seams three coats of epoxy, building up enough so sanding would

eliminate the tape shoulders. Worked pretty well.

We moved the hull outside for the sand-down. There was a slight breeze

blowing, so we didn't get too prickly. And we both wore Tyvek suits,

surgical gloves, and face masks.

Back inside, the hull was ready for its covering of 6 oz. fiberglass

cloth. That was a job, but somehow we got it done without many wrinkles.

Actually, instead of trying to drape the whole hull at once, we did half

at a time, lapping the centerline by about three inches with right and

left layers. Seemed easier to control that way.

Once again, three coats of epoxy along with interim sanding to smooth the

hull out.

As this boat is a personal kayak, I put an additional bulkhead of

closed-cell foam at the forward end of the cockpit, measuring my own leg

length to decide where to place the bulkhead. So, Adelante (as the kayak

was later named) now has a watertight space between the forward bulkhead

and the foam bulkhead, a kind of insurance policy, I suppose. Other than

this, there is no watertight space in the entire kayak, as both bow and

stern have access hatches.

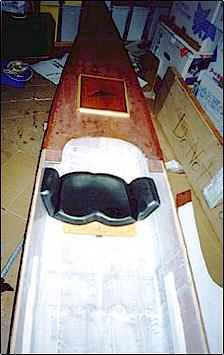

Bulkhead installed, we place the decks--three large pieces of plywood.

Spring arrives. Work speed increases. But still, it takes until late May

to get the finishing touches complete.

Bulkhead installed, we place the decks--three large pieces of plywood.

Spring arrives. Work speed increases. But still, it takes until late May

to get the finishing touches complete.

Even after the cockpit coaming is on and epoxied, we still have to install

the seat and the backrest and the hatch cover straps and the . . . it

seems to take forever.

But in the end, Adelante turned out to be an eye catcher. Yellow hull with

red trim and natural wood decks. Lauan rubrails, epoxied and varnished,

with their bronze screws visible, add a bit of character to the craft.

Black webbing to hold down the hatches, deck lines, and shock cord webs.

Black circumference deck line, yellow tow line . . . the list goes on. But

perhaps the crowning feature is the inlaid stern hatch cover, which

features my personal logomark, a singing humpback whale, which my friend

Rick the Mouseherder (www.mouseherder.com)

calls the Wailing Whale. Rick made the Adelante name graphics for the

kayak.

Adelante cruises along the Miura and Boso peninsulas around Tokyo

Bay in Japan, but she has yet to see a dolphin. And I have yet to master

the Eskimo roll.

# # # |