Before hauling out to build the Navigator conversion, “Oink” had

suffered damage while lying neglected on an exposed mooring. Thousands of

slaps and bangs under that flat bow had caused ongoing damage, culminating

in the mast coming down due to wear around the fid and mast step. Extra

inertia caused the tabernacle supports to rip out the top layer of the

marine ply side, and down she came, splitting the main bulkhead clear

across. There are often posts to the Bolger Group,

|

Oink as originally built |

requesting ways to reduce flat bow slaps and gurgles, which keep people

awake at night, and it seemed to me a permanent solution was

best, and now was the time to do it. By the way, the flat bow

is fine while sailing, and people with less difficult conditions

have no problems with damage, except getting some sleep!

A false rounded bow underbody seemed the best answer. I wanted to

leave the ply bottom in place so she would stay in shape, and first

thought of a molded ply fabrication, but this would have been difficult

because there would be no access to the upper side. A solid lightweight

shaped addition appeared to be more practical. Bolger has shown ideas for

solid timber shapes glued in place for larger boats, but their roundness

was limited and probably inappropriate for lightweight Navigator. Newer

designs have sacrificial ply bow extensions filled with foam, and this

would be a very good method for a new boat. Styrene and epoxy, surfboard

style looked practical for my situation, and questions to

rec.boats.building popped up some very helpful advice from a surfboard

maker in Asia! Ah, the miracle of the Net.

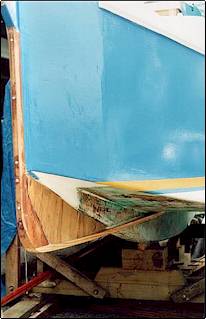

|

stem piece first then keel

battens

faired to hull with fitted hardwood deadwood infill |

To achieve a rounded softer entry, one is limited to the space between

the existing chine line, and a new lower keel line; any deeper and one

would end up with a Yorkshire Coble, and the bow would take charge of

steering the boat. Measurement showed I could add onto the existing bow, a

new stem, extending 250mm (10”) below the present stem/chine/bottom, and a

keel line could run aft and blend with the deepest point of the existing

chine/bottom. The stem was glued in place first, followed by a false keel,

150x20 (6”x1”), slotted to fit the existing keel and tapered to the new

stem. The space left was filled with solid deadwood as pictured.

Blue Styrofoam in sheets was the recommended base material, because

it can be epoxied without melting. The first sheet, 35mm thick, was glued

flat against the ply bottom for the full length of the new shaping, and

subsequent sheets were shorter each time to match the new bottom line, and

to reduce wastage. Epoxy was used for bonding the first layer to the flat

ply bottom, and here the most difficult part of the whole operation reared

its head - working on your back applying glue, goo and pressure upwards.

All epoxy had to be thickened to stay up. A system of cross-timbers,

vertical struts and wedges gradually forced the gluey sheets (one each

side) firmly into place, but it was a real struggle, involving every curse

known to civilised man. As one wedge was tapped into place, inevitably the

previous wedge, or two wedges ago, strut and caboodle would drop out, due

to the flexible 6mm ply of the original bottom. Every one of the 40 wedges

on each side was re-jigged 2 or 3 times. Then when I had finished,

struggled out and leaned against the boat in relief, the whole damned ship

swayed and nearly toppled! She was now floating above the cradle on many

little hands. I was very relieved when the epoxy set and the boat could be

sat down again.

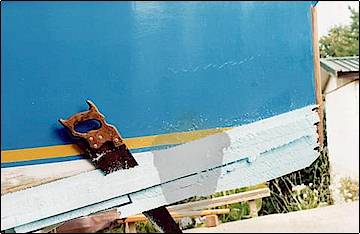

|

Sheets stepped towards bow

to follow keel line

and glued with contact adhesive for easy fairing. |

The first life-saving tip from my surfboard friend came next – fix

subsequent layers of foam with contact adhesive, never epoxy. Fairing is

fun enough, without hard lines of glue sailing across the fairing lines.

One quickly learns just how soft the foam is. Even a swipe with the back

end of a plane will gouge a chunk out. Contact adhesive worked well, but

you must force yourself to wait for the glue to “set” before you place the

sheet, as the manufacturer states. And when it is ready, the sheet must be

held exactly square before pressing upwards, because you get only one

chance. No clever sliding fits! But with care it went well.

|

Faired with saw electric

planer

and sandpaper boards |

Fairing. Uggggggh!!!!!! Sawing the side projections took seconds. The

rest took hours and hours and hours. I tried all possible tools, and found

the best tool to form the basic shape was an electric hand planer. I hate

this effective but most dangerous of electric tools, and swinging the

plane above my face, blinded by a snowstorm of blue confetti was no fun at

all. But very effective. It shaped cleanly with little tearing, though if

the day had been windy, the whole neighbourhood would have been blue!

Earlier, I had drawn a measured and faired drawing of how the bow would be

shaped. In the end it was all too difficult, and I threw the drawing away

and shaped by eye. This was not as hard as it sounds, because the layers

of styrene could be faired evenly by comparing the curved joints on both

sides – rather like shaping a plywood centreboard. Sanding blocks and

boards were tried, but were not greatly useful because of the tight curves

in this bow region.

The second life-saving tip came next – don’t try and fair the styrene

to perfection before filling, glassing and epoxying. It will drive you

mad, because you will damage the surface everytime you go near it, and

cause further damage trying to correct the first damage. If you try and

fill raw styrene, the softest filler is denser than the foam, and sanding

rips away the surrounding styrene, leaving a lump of filler! When the

shape is reasonably fair, with no major lumps and bumps, coat the foam

with epoxy and glass cloth. This gives a firm base to which you can then

apply and sand filler. Overhead glass and epoxy was another trial by fire,

but I got there in the end.

|

You cannot completely fair

the foam because it is very soft.

A nudge with the plane will dent it |

First I epoxied wide tape along the chines and keel, in case the

fairing ever decided to come off in one lump! Two layers of the heaviest

cloth stocked by the boatshop were used for the main surface(10oz I

think), and two further coats of epoxy. The amount of fairing you can do

towards achieving perfection is infinite, and as my surfboard man said,

you will know when you reach the balance between perfection and

condemnation! For the larger concavities I used epoxy thickened with

microballoons, and on wider thinner areas, house type exterior white

acrylic paste, applied with a plasterers steel float. I have used this

before, and found it to be just as durable as much more expensive and

unfriendly materials (epoxy), but only in non-structural applications.

|

Bow rounded primarily to

stop noise

and destructive pounding while moored. |

I think the bow will work. It is certainly much more solid than before;

hitting it with your fist sounds more like a Rolls Royce door closing than

a kettle drum! Probably the stem will be an inch or two below water. If

not, ballast may have to be added inside to compensate and adjust the

trim. If we hit anything, I would expect collision damage to be less than

before the addition. The foam may be dented or chewed, but should be

easily filled and faired. Extra floatation will be a benefit in the

unhappy event of a hull breach.

I also hasten to add that I have not asked, and don’t have the blessing

of Mr Bolger for this change; it’s at my own risk. The more I work at

changing this boat to meet my needs, the more I admire Bolgers original

concept of Micro - extreme simplicity and economy. Every change I make

seems to involve yet more sheets of ply and expense. But hey, we are

supposed to be having fun.

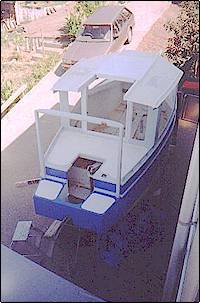

Other Progress

|

windows in roof to come,

rear deck tiller enclosure to come,

extended stern floatation both sides

and future hinged motor hatch |

The photo from above the boat shows the main rear deck completed. This

space is really just for access and a platform from which to tend the

outboard. Bolger intends Navigator to be steered from inside the cabin,

where crew weight is best positioned for the trim of such a short boat. My

added low deck extension aft, is to provide protection for the motor; also

Micro though a tiny boat, when approached in choppy water can be

dauntingly high above a small dinghy. The low rear decks should provide an

easy boarding point, with the stanchions right there to heave oneself

aboard.

I connected the stanchion tops with a hardwood plank, to provide a

base for a mainsheet traveller, and to help support my standard Micro

mizzen mast. The plan showed a heavier alloy tube, because the chinese

mainsail sheets are sheeted to it, but I reused my old mast to save cost.

The plans are short on detail about the sheeting in this area, but seem to

show them running into the cabin above the rear deck at cabintop height.

Stumblebums like myself would be prudent to lead them under the deck and

through the tiller slot, to cabin cleats. Angled uphill so water will not

run down them and into the cabin!

|

gunwale cut down and bow

extended, bowsprit for possible extras |

The front shot shows the new mast support in place. A fly speck below

the yellow boot top is actually a drain from the forward well. The bottom

of the well has been lifted towards the rear by floating in an

epoxy/concrete reinforced mix. This was to avoid drain tubes through the

styrene layers to exit through the bottom, which if disturbed may have

allowed water penetration into the foam, and would also be vulnerable to

blockage by marine growth. I once bought a 30ft trimaran for a good price,

because the owner was sick and tired of mysterious flooding. I later found

that an underwtaer cockpit drain would block with marine growth, and at a

certain point the main hull filled with a rush through a toilet fitting,

sinking the boat down to the level of the bunks.

Next job, the cabin interior and rigging.

Don Baldwinson

oink@paradise.net.nz |