|

Building a Standard Pygmy

Goldeneye

in Juneau, Alaska - Fall to Summer

by Katy McKerney Katy_McKerney@envircon.state.ak.us

| My friend, Johanne Nelson (Joey) and I wanted kayaks in the worst

way. After all, we both live a stone’s throw away from an Alaska Inside Passage

waterway. Joey insisted that she wanted to build a wooden kayak. BUILD ONE? She patiently

explained that since we are both of Norwegian descent, we HAD to build one..a Nordic

tradition. All I reasoned was that I didn’t want her to have a cool, one-of-a-kind

kayak with me having an anyone-can-own store bought kind. We both live in condos so, we

decided to build them at the only place we could find, the University of Alaska-Southeast

Marine Technical Center. |

We

decided to pick our own stitch and sew kit design, although we really didn’t know

what stitch and sew meant exactly. We naively imagined that all we had to do was.. stitch

and sew boat parts, glue stuff…grab our paddles and head for the nearest Alaska

postcard scene, like a whale siting or glacier, where photographers would be waiting to

snap shots of us (cool Alaskan dudettes) for Outside Magazine. We

decided to pick our own stitch and sew kit design, although we really didn’t know

what stitch and sew meant exactly. We naively imagined that all we had to do was.. stitch

and sew boat parts, glue stuff…grab our paddles and head for the nearest Alaska

postcard scene, like a whale siting or glacier, where photographers would be waiting to

snap shots of us (cool Alaskan dudettes) for Outside Magazine. |

| With maybe…oh..at the outside..an hour of research (and

someone said they saw a Pygmy boat and it looked real neat and real wooden) we

decided to buy Pygmy Goldeneye kits from Port Townsend, Washington at $600.00 per kit. |

|

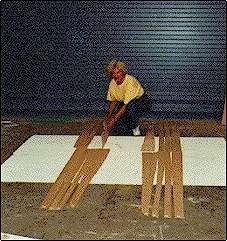

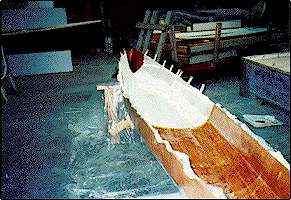

With great anticipation we peered into the kit boxes and gingerly

laid out 20 hull panels for one kayak. The panels were cut from 4 mm marine grade mahogany

ply. We stared in disbelief at $600.00 worth of very flat, very un-kayaky-looking pieces

of super-thin plywood. All the panels were odd shaped and none of them looked remotely

like they fit together. We learned that because boats are curved for floating, the pieces

are cut to fit once the hull is curved into position. They don’t fit laying on a flat

surface. Still, we tried to suppress an element of panic thinking we just got soaked for

$1200.00 and who’s idea was this anyway? JOEY?? |

| Apprehension was replaced by serious concentration as we spent our

first 4 hours of kayak building trying to read the kit design directions and figure out

which hull panels went together in order to join them with butt plates. Why do they call

them butt plates? We never did figure that one out. |

| Every six inches, 1/16 inch holes had to be drilled along the

upper edge of each of the hull planks except the sheer. Assembling the

hull involved wiring the two keel panels together and then gluing in temporary frames.

Then we cut a bunch of wire into 3 ½" lengths and inserted them into the drilled

holes and twisted the wire ends. |

|

|

This is where stitch and sew boat building gets its name. Our

fingers got pretty sore after doing all the panels. Hey, no one told us we’d get SORE

building a kayak. It was the first of many times we would reflect on how some hidden

muscle on us ached from the endless sanding or from getting into yet another Houdini

position to glue something.

|

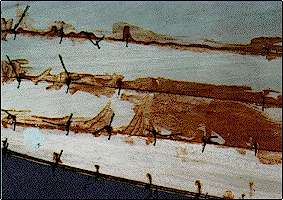

| Once the inside and outside hull seams are glued,

then all the "stitches" or wires have to come out. The exercise of getting the

wires out proved to be interesting since they were essentially epoxied in.

|

|

|

It is very easy to slather on the glue especially

with the thought in mind that you don’t want your boat to leak. Joey did just that,

using epoxy generously to seal the seams, but it gushed out all over the hull. All the

extra glue then has to be sanded off before doing the next step. Initially, neither of us

realized how much sanding we were in for throughout the project. Glue then sand, glue then

sand fa la la la la. |

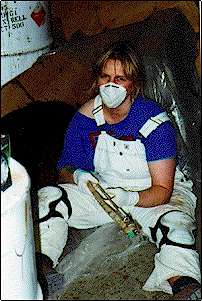

| Another thing we didn’t realize is that we would look like

large insects most of the time due to wearing breathing apparatus. Our vision of being

sexy little boat builders vanished with the first lesson on how toxic epoxy is to breathe

and get on your skin. |

|

|

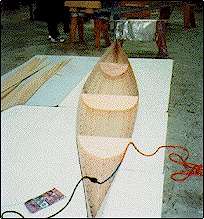

The hull then had to be glassed with sheathing cloth.

Many of the steps are awkward to do alone so Joey enlisted the help of her boyfriend. The

sheathing cloth is very slippery and wants to be in a heap on the shop floor. I

had to become somewhat creative to keep the sheathing cloth on the hull. For example, I

used clothespins to hold the cloth in place. |

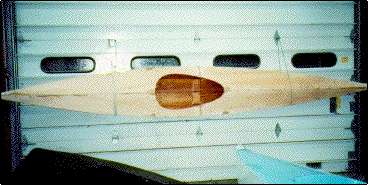

| Once the epoxy is spread onto the cloth sheathing, it

turns from white to clear and the wood grain magically appears |

|

|

The deck was then reinforced, wired and positioned on the hull to

ensure that it would fit properly. This step was tricky. It was also why we were glad we

bought pre-cut pieces, especially being novices. If the pieces aren’t cut just right,

they won’t fit together. The deck is then removed and we come back to it later. Someone

in the shop built a kayak from scratch and made a few modifications to the original

design. They forgot to make some critical adjustments and when they went to try out the

kayak in late spring, it kept tipping it’s builder out into the icy sea. The kayak

was a total loss. |

| Glassing the inside of the hull was next. This was

also challenging because the sheathing cloth wants to slide to the bottom of the boat.

Annoying epoxy bubbles take on a life of their own in this step. Every time I thought I

had them all smoothed out they would mischievously bloop up again. arghhh… |

|

|

Gluing on the deck came next. Although the boat designer stated in

the directions that the way to glue on the deck was to tip the boat up on it’s sheer

on the floor, it is an understatement to say that it didn’t work for me. I just

wallowed around on the cold, cement floor, half in and half out of the boat squirting glue

everywhere but on the seams. This approach only served as entertainment for the other boat

builders. I also learned my first lesson about coming into contact

with freshly sanded, uncured epoxy. I wore a tee shirt on my first attempt at gluing on

the deck and ended up with a nasty epoxy rash all over my arms. |

| Finally someone took pity on me and said that the best way to glue

on the deck is from a standing position achieved by hanging the kayak on large garage

doors. Everything went much smoother once I did that. |

|

|

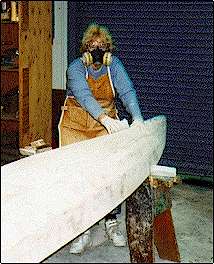

Once the deck is glued on, then the next step is to

glass the deck. After my initial case of epoxy rash, I wore long sleeved coveralls and

duct-taped my wrists so no epoxy dust could get in! |

| The cockpit coaming was then installed. Joey decided

not to put in bulkheads and hatches and opted for the simpler approach. I decided to

install bulkheads and hatches, and we both had to install the seats, mount the foot

pedals, hand toggles, deck rigging, and finish the hull. It took me about a month to

finish the hull with several coats of varnish. |

|

Joey and I took our kayaks on a maiden voyage to

Berner’s Bay located north of Juneau. The weather turned and we never made it out of

the cove. Joey took this picture minutes before high winds came rolling into the cove and

we had to scamper back to the boat launch. Later on, after a week trip around

Wrangell Island in SE Alaska I decided that a rudder would be a definite asset. I

installed a rudder with the help of a fellow boat builder. As usual, it turned out to be

more complicated than I expected! Beware of boat designers who state up front that it will

only take a measly number of hours to build a boat using their kit. HA HA HA HA HA HA Joey and I took our kayaks on a maiden voyage to

Berner’s Bay located north of Juneau. The weather turned and we never made it out of

the cove. Joey took this picture minutes before high winds came rolling into the cove and

we had to scamper back to the boat launch. Later on, after a week trip around

Wrangell Island in SE Alaska I decided that a rudder would be a definite asset. I

installed a rudder with the help of a fellow boat builder. As usual, it turned out to be

more complicated than I expected! Beware of boat designers who state up front that it will

only take a measly number of hours to build a boat using their kit. HA HA HA HA HA HA

|

|

![]()