|

The Design

I have wanted to build a trailer-sailer for coastal cruising

for some time now. Back in 1995, my son Bonham and I built

a Bolger designed Tennessee.

He was fifteen, and wanted nothing to do with no sailboat.

The mistake I made was in subjecting him at an early age to

the supreme embarrassment of riding in a 16ft sailboat while

really fast and impressive motor boats zipped past us in all

directions. No, he would not help me build one of those

worthless things. He wanted a boat for fishing.

At that point, I hatched the idea of us building a cabin cruiser.

We could go to the coast for a week at a time, and fish 'til

we'd had our fill.

He went for it, and

after about nine months of Saturdays, we ended up with a great little OB camp

cruiser. We went to the coast and fished and fished.

Unfortunately boys grow up, and as in Bonham's case, go off to

college. At that point, I somehow convinced my better half,

Sandra, to go for a cruise with me in the Tennessee. To my

astonishment, she actually liked it! So, never one to let good

enough alone, I told her that it would be lots more fun cruising in

a sailboat. As I held my breath, she replied,

"Lets build one", and the search was on for the perfect

design. He went for it, and

after about nine months of Saturdays, we ended up with a great little OB camp

cruiser. We went to the coast and fished and fished.

Unfortunately boys grow up, and as in Bonham's case, go off to

college. At that point, I somehow convinced my better half,

Sandra, to go for a cruise with me in the Tennessee. To my

astonishment, she actually liked it! So, never one to let good

enough alone, I told her that it would be lots more fun cruising in

a sailboat. As I held my breath, she replied,

"Lets build one", and the search was on for the perfect

design.

Being a Bolger builder, not to mention a big fan, I had my

eye on one of his designs. Martha Jane is a 24' trailerable

cruiser. She has water ballast for light trailer weight, low

tech sails for simplicity, leeboards for shallow draft, a folding

mast for quick setup, and room enough for two for a couple of weeks

of fun on the water. This seemed at first blush like that

elusive perfect boat, until I found out that she weighed 1500

lbs. I have always driven small vehicles, so that weight was a

little on the high side. My tow car of choice was to be my

four cylinder Ford Ranger.

So what does that leave? There are lots of smallish

boats with little cuddy cabins made for elves. Problem was,

Sandra was spoiled by the separate galley in the Tennessee.

Just when I was about to decide I needed a bigger truck, along came

Jim Michalak's Caprice.

Jim designed the boat for Bill Moffitt, whom I corresponded

with. He was not quite ready to begin building at that

time, but I sure was. This boat was everything the Martha Jane

was but somehow she was 600 lbs lighter. The layout of the two

is very similar, the main difference being Caprice's multichine hull

(The MJ is a flat bottomed sharpie). I got the plans right

away, and began to study them.

Building the

hull

My philosophy of boat building is based on two

assumptions: 1) You will never get much when you sell a homemade

boat, even if you use the most expensive materials. 2) the fun you have

with a boat is inversely proportional to

the concern you have for its appearance. This leads me to

believe in building quick and dirty boats. I have heard it

described as building to workboat finish. Whatever you call

it, I use inexpensive materials but not junk. I buy Douglas

Fir plywood for its strength, light weight, and rot

resistance. We can't really get fir lumber around here, so I

use Southern Yellow pine where strength is needed, and Western Red

Cedar where I want less weight. I never use

"whitewood" or any soft hardwoods like Poplar, or Birch.

This would be my first stitch and glue boat, but with five

other boats under my belt, I wasn't too concerned. She goes

together "instant" fashion: no strongback is

used.

The first job was to build the bulkheads. These are

plywood with some framing pieces around the edges where they will

attach to the skin. The bulkhead that the mast tabernacle

attaches to has framing pieces cut from 2"X 8"

material. The first job was to build the bulkheads. These are

plywood with some framing pieces around the edges where they will

attach to the skin. The bulkhead that the mast tabernacle

attaches to has framing pieces cut from 2"X 8"

material.

Next the sides are built by joining four 1/4" ply pieces

together edge to edge. I used the Payson tape method but with

epoxy: Two layers of glass tape in resin over the joint. I did

some joints both sides at once, and some one side at a time. I

discovered that the most important thing is to have a level, flat

surface under the joint.

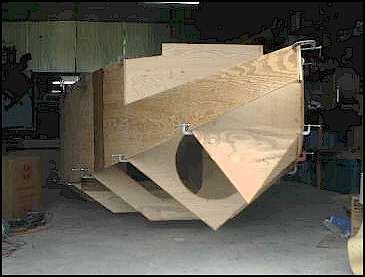

The boat goes 3D when the sides are screwed and glued to the

bulkheads. I did a dry run with the whole thing right side up

just to get a feel for the size of the boat (see picture on right). This also gave me

screw holes to follow when I got the glue ready. The hull was assembled

upside down using thickened epoxy in the joints, and square drive SS

screws from www.mcfeelys.com

. The centerlines of the bulkheads are marked, and kept

straight by way of a stretched string. The boat goes 3D when the sides are screwed and glued to the

bulkheads. I did a dry run with the whole thing right side up

just to get a feel for the size of the boat (see picture on right). This also gave me

screw holes to follow when I got the glue ready. The hull was assembled

upside down using thickened epoxy in the joints, and square drive SS

screws from www.mcfeelys.com

. The centerlines of the bulkheads are marked, and kept

straight by way of a stretched string.

For gluing, I use fumed silica (which made my wife

extremely nervous as she worried about the dangers of inhaling

silica) from www.raka.com

mixed with resin to the consistency of Vaseline. It is best to

precoat the surfaces to be joined with liquid epoxy, and let it get

tacky before gluing. When some of the thickened resin squishes

out of the joint, you can make a little fillet

there.

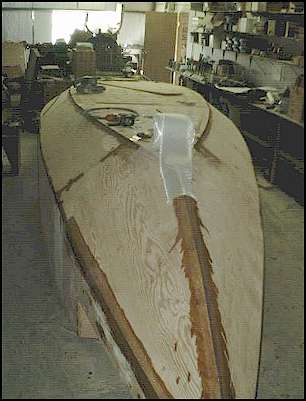

The bottom is two layers of 1/2" ply with the joints overlapping.

The pieces are first precut according to Jim's excellent

instructions. I predrilled the second layer with 3/16"

holes on 6" centers to accept temporary drywall clamping

screws. It helps to use screws long enough to go through the

two layers, and to spray the screws with WD-40 to make them easy to

remove.  I applied the first layer of ply across the bottom

with glue and screws at the bulkheads, and temporary butt blocks underneath the

joints. Then, when I had a block of free time, I used a roller to coat

the bottom and the second layer of 1/2" ply with epoxy, putting the

screws in as I went, to glue the whole bottom lamination up at once. I put the clamping screws in, in the direction that I am

putting the ply pieces down, so that the excess resin was squeezed

onto the next area to be laminated. Later I removed the drywall screws,

filled the holes (see picture on left), and removed the temporary

butt blocks. That was time consuming, but I don't know of a

better way to do a good job of it. I applied the first layer of ply across the bottom

with glue and screws at the bulkheads, and temporary butt blocks underneath the

joints. Then, when I had a block of free time, I used a roller to coat

the bottom and the second layer of 1/2" ply with epoxy, putting the

screws in as I went, to glue the whole bottom lamination up at once. I put the clamping screws in, in the direction that I am

putting the ply pieces down, so that the excess resin was squeezed

onto the next area to be laminated. Later I removed the drywall screws,

filled the holes (see picture on left), and removed the temporary

butt blocks. That was time consuming, but I don't know of a

better way to do a good job of it.

The next step is to cut out the bilge panels and wire them

between the bottom and the sides. I put scraps up to the

gap, put a couple of screws in to hold them in place, then crawled

under the boat, and marked where they needed to be cut to more or

less fill the space. This is not a critical fit, as the

filleting and taping covers gaps (in my case) of over a half

inch. Once the bilge panels were "stitched" in

place, I returned to the underside of the hull, and duct taped all

along the seams.  I used epoxy from www.raka.com

mixed with wood flour to fill the seams, after brushing liquid resin

on to prime them. There are different ways of handling the tie

wires (I used baling wire), but I just puttied up to about an inch

from them, removed the wires when the epoxy was set, and finished

filling those little gaps. The belt sander (fifty grit) did a

quick job of smoothing out the lumps in my seams.

I used epoxy from www.raka.com

mixed with wood flour to fill the seams, after brushing liquid resin

on to prime them. There are different ways of handling the tie

wires (I used baling wire), but I just puttied up to about an inch

from them, removed the wires when the epoxy was set, and finished

filling those little gaps. The belt sander (fifty grit) did a

quick job of smoothing out the lumps in my seams.

For taping the external seams, I use 12oz. biaxial tape (again

from RAKA) first a three inch

layer, then, a six inch one. After everything cured, I used a

random orbital sander to feather the edges of the tape. This part went very fast, and soon

I was ready to cover the whole hull with 2.5oz cloth. This

may seem a little light, but it was mostly to prevent checking of

the fir ply. I have found that the bottoms of boats where we

cruise don't get much damage from the abundant sand and few rocks. It was difficult

(next to impossible) to get all the wrinkles out of the

light fabric, but heavier stuff would have eaten a lot of epoxy.

I

have agonized a lot over paint. Considering my above mentioned

philosophy about building cheap boats, I was not going to use one of

those $50 a quart wonder paints. On the other hand, we put

some Wal-Mart house paint on the topsides of the Tennessee, and it

came off in sheets after a day in the water. On that same

boat, we used some latex floor enamel for the bottom, and it did

great. Still, I thought that an oil based floor paint would be

really good. I got a nice green brand name enamel from McCoys.

It sold me with two magic words on the label: boats, and

polyurethane. Was this the high dollar stuff for twenty bucks a

gallon? Who knows. Now that it is cured, it seems pretty tough, but I had

my reservations for a while. We painted the hull on a typical

West Texas summer day - temperature near a hundred, and humidity

near zero. I thought it was perfect for drying paint.

The next day I

came back expecting to find the paint somewhat dry, but no, it was

perfectly wet. By the third day (with big fans running and all

doors open) I called the company. The tech guy said that this

was typical for paint over epoxy, and sure enough it did dry in

about a week. The second coat dried overnight. Go

figure. I

have agonized a lot over paint. Considering my above mentioned

philosophy about building cheap boats, I was not going to use one of

those $50 a quart wonder paints. On the other hand, we put

some Wal-Mart house paint on the topsides of the Tennessee, and it

came off in sheets after a day in the water. On that same

boat, we used some latex floor enamel for the bottom, and it did

great. Still, I thought that an oil based floor paint would be

really good. I got a nice green brand name enamel from McCoys.

It sold me with two magic words on the label: boats, and

polyurethane. Was this the high dollar stuff for twenty bucks a

gallon? Who knows. Now that it is cured, it seems pretty tough, but I had

my reservations for a while. We painted the hull on a typical

West Texas summer day - temperature near a hundred, and humidity

near zero. I thought it was perfect for drying paint.

The next day I

came back expecting to find the paint somewhat dry, but no, it was

perfectly wet. By the third day (with big fans running and all

doors open) I called the company. The tech guy said that this

was typical for paint over epoxy, and sure enough it did dry in

about a week. The second coat dried overnight. Go

figure.

The turn-over went well with nothing broken. I called a

bunch of friends, and we just picked it up, and turned it in

place. Wow! There was a boat under there. Now

we're getting somewhere. First though, we had a little more

work to do. After pulling out all the duct tape, I got ready

for glass taping the inside of the seams. Jim Michalak instructed me

in this process, and his method made it truly a breeze. The

first thing to do is to pick an area that you can do all at

once. After grinding off any protruding epoxy warts, prime the

joint with liquid epoxy. When that coat is tacky, use a wood flour

mix the consistency of peanut butter to make the fillet. I use

a metal paddle about an inch wide and rounded on the end. What

makes Jim's method easy is this: Apply the tape while the

fillet is still soft. In fact, apply both layers at the same

time. You may have to go back over the joint while it is

curing with some additional liquid, as it tends to run down and out

of the weave of the tape. When everything sets up, you only to

have to sand it once, and you are done. I need to give Sandra

special credit here of mixing epoxy and cutting tape all through

this process, thus saving me having to climb in and out of the

boat. In fact, she was a big help throughout the whole

process.

Leeboard

About this time, I put the big lee board together. I

was a little dubious about building it out of all ply, as per the

plans, since I had

been aboard one boat (Scram Pram) when the board failed, and had

heard a report of one on a June Bug. What I decided to do,

instead, was to lay a board core, and use ply on the outsides, then

cover the whole thing with a layer of glass. It was pointed

out the I should have used the boards on the surface where the

compression and tension strength was needed, and ply in the

center. This would have made the whole thing too thick unless I had

planed the boards down. About this time, I put the big lee board together. I

was a little dubious about building it out of all ply, as per the

plans, since I had

been aboard one boat (Scram Pram) when the board failed, and had

heard a report of one on a June Bug. What I decided to do,

instead, was to lay a board core, and use ply on the outsides, then

cover the whole thing with a layer of glass. It was pointed

out the I should have used the boards on the surface where the

compression and tension strength was needed, and ply in the

center. This would have made the whole thing too thick unless I had

planed the boards down.

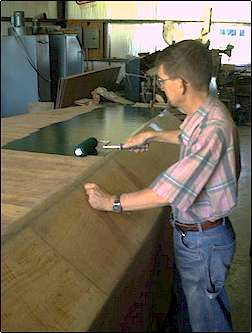

Phil Bolger once suggested using two courses of boards glued

together where the first course used several boards edge to edge (as

in the picture above). The second course would begin with one

of the boards ripped diagonally from corner to corner. The two

resulting triangles would be positioned at the edges of the

previously assembly, and the remaining boards placed between so that

all the joints are overlapping.

Ballast Tanks

The

ballast tanks were easy to do. I basically framed them up,

taped the seams, and

epoxied the inside of two of them. I glassed the other two.

The covers I made out of ply and gave the same treatment. The

purpose of using two different techniques was to use the boat as an experiment. I

had observed that plywood that is not exposed to sunlight would not

check, but would remain sealed with epoxy alone. On upper

decks, however, Doug Fir ply will open right up no matter how much

epoxy is on it, even if resanded and re epoxied after a couple of

years of exposure. A thin layer of glass or other fabric will

stop this nonsense. That means that the tanks should be Ok

with epoxy only, right? I was not convinced, thus the

experiment. The

ballast tanks were easy to do. I basically framed them up,

taped the seams, and

epoxied the inside of two of them. I glassed the other two.

The covers I made out of ply and gave the same treatment. The

purpose of using two different techniques was to use the boat as an experiment. I

had observed that plywood that is not exposed to sunlight would not

check, but would remain sealed with epoxy alone. On upper

decks, however, Doug Fir ply will open right up no matter how much

epoxy is on it, even if resanded and re epoxied after a couple of

years of exposure. A thin layer of glass or other fabric will

stop this nonsense. That means that the tanks should be Ok

with epoxy only, right? I was not convinced, thus the

experiment.

I put the tank tops down with silicone and lots of SS

screws. There is a Beckson type port in each (see picture

above), and a regular 1" transom plug in the bottom under each

side. the adjoining tanks are connected with openings so that

one opening will flood both tanks. A Rule 1000 GPH bilge pump

is located on each side to empty the tanks before retrieving, or for

motoring. So the filling process is as follows:

Open the observation ports P&S; Remove the plugs; Wait for the

tanks to fill; Replace the plugs; Replace the inspection port

covers.

Spars

I

could not find any Fir or Spruce for a decent price, so I decided to

use Western Red Cedar which is abundant and cheap in our area.

This is a light wood similar to redwood with little strength, so I

figured I needed to cover it with glass. I found some

unidirectional 9 oz. material, and used two layers on each

spar. I

could not find any Fir or Spruce for a decent price, so I decided to

use Western Red Cedar which is abundant and cheap in our area.

This is a light wood similar to redwood with little strength, so I

figured I needed to cover it with glass. I found some

unidirectional 9 oz. material, and used two layers on each

spar.

There are six sticks on the boat: main & mizzen masts,

yardarm, main boom, sprit boom, and boomkin. I only used Red

Cedar for the first four. For the sprit boom, I had my eye on

regular Southern Yellow Pine closet pole material. This stuff

is clear, strong, and comes in 8 foot lengths. I made the

boomkin out of a 2 X 4 of the same material. SYP is heavy but

strong and cheap, and I figured that since it was located low in the

boat, there would not be too much of a penalty.

I could have used the birdsmouth method, and would like to do

that sometime, but for this project, I elected to scarf and laminate

solid blanks to make the spars out of. I used epoxy to glue

everything up, then bandsawed the taper, and used my belt sander to

smooth them up. Then the glass was added. So far they

seem to be holding up.

Finishing Up

One

thing we did that turned out to be of uncertain value was to paint

the interior of the cabin before adding the the top. I say

uncertain because by the time we had the top on, the painted

surfaces were pretty shopworn, and required repainting anyway.

the rest of the finishing was pretty routine. We did so one

thing in the cockpit that I thought worked out pretty well. We

wanted some kind of nonskid surface that would not require too much

maintenance and would be cheap and good looking. We hit on the

idea of cutting the scraps of Cedar into strips about 3/8th by 1.5

inches and gluing them to the surfaces of the bridge deck and

footwell. First we cut out the plywood pieces for those areas,

then we arranged and glued the strips down. When the epoxy had

set, we painted between the strips, and glued the assemblies into

the boat. I thought it made a nice job. One

thing we did that turned out to be of uncertain value was to paint

the interior of the cabin before adding the the top. I say

uncertain because by the time we had the top on, the painted

surfaces were pretty shopworn, and required repainting anyway.

the rest of the finishing was pretty routine. We did so one

thing in the cockpit that I thought worked out pretty well. We

wanted some kind of nonskid surface that would not require too much

maintenance and would be cheap and good looking. We hit on the

idea of cutting the scraps of Cedar into strips about 3/8th by 1.5

inches and gluing them to the surfaces of the bridge deck and

footwell. First we cut out the plywood pieces for those areas,

then we arranged and glued the strips down. When the epoxy had

set, we painted between the strips, and glued the assemblies into

the boat. I thought it made a nice job.

I

got a good deal on a used trailer, so I went with that even though

it took a little modification. I had to extend the tongue

eight feet. Then I built a couple of bunks out of treated pine

4 X 4s. At first I covered the bunks with regular carpet

scraps, but the boat did not want to slide on and off these very

well, so I substituted strips of polyethylene "Astroturf"

welcome mats from Walmart, and they work much better. I

got a good deal on a used trailer, so I went with that even though

it took a little modification. I had to extend the tongue

eight feet. Then I built a couple of bunks out of treated pine

4 X 4s. At first I covered the bunks with regular carpet

scraps, but the boat did not want to slide on and off these very

well, so I substituted strips of polyethylene "Astroturf"

welcome mats from Walmart, and they work much better.

Sandra and I got the boat onto the trailer all by

ourselves. We used 1" dowels for rollers, and she slid

right onto her berth. It did help that it was down hill most

of the way.

In a later article, Sandra will tell about making the sails,

and soon we will have some cruises to report on.

|

![]()